For a whole year after my mom died from a virus that turned our country into one long argument, a biker in a torn leather jacket showed up at her grave every Sunday morning and I was sure he was there out of guilt. Every week at nine on the dot, while I sat in my car gripping the steering wheel, he parked his loud motorcycle by the oaks, walked straight to her headstone, and knelt like he was praying to someone he’d wronged.

The first Sunday I saw him, I thought he was lost.

The cemetery is big, the sections all look the same, and people wander around all the time, clutching faded maps from the office and squinting at rows of stone.

But he came back the next week. And the next. And the next.

Same bike, same black boots, same patched jacket that looked like it had seen more fights than church pews.

He never brought flowers. Never carried a Bible.

He just sat on the grass at my mom’s grave, hands on his knees, head bowed.

My mom’s name is Denise Carter.

She drove a city bus for twenty five years, the same line across our fading industrial town, past closed factories, payday loan shops, and the one shiny hospital people pretended meant things were improving.

They called her an “essential worker” when the outbreak hit.

Essential, but they didn’t give her a fancy office, or a personal driver, or enough health insurance to make her feel safe.

They gave her a cloth mask, a small bonus, and a timetable with more shifts.

She got sick in the second winter of it all.

Cough, fever, then the hospital.

We talked on video until she was too tired to hold the phone.

When she died, it was just me and my sister at the graveside, standing six feet away from two masked workers lowering the casket.

The pastor mumbled into the wind.

There was no choir, no crowded church, no potluck afterward with neighbors telling stories and passing around casseroles.

What we got instead was a short segment on the local news.

They showed her picture for ten seconds, called her “a beloved bus operator and pillar of her community,” and moved on to the latest argument about restrictions and protests and who was to blame for what.

So when that biker started showing up, a part of me took it personally.

He didn’t look like the kind of person my mom would have known.

He looked like the kind of man people point at on talk shows when they want to prove some point about “what’s wrong with America.”

I watched him from my car week after week.

It wasn’t just curiosity.

It was this heavy mix of grief and anger and suspicion that had been sitting in my chest since the day my mom’s ventilator was turned off.

Why was he here for her when some of her coworkers hadn’t come once?

Why could he kneel at her grave when I still had trouble standing there more than five minutes without feeling like the ground was tilting?

My mom and I, we weren’t on the best terms before she got sick.

We loved each other, sure, but there was this one fight that sat between us like a piece of furniture nobody could move.

She got a “hazard pay” bonus early in the pandemic, a chunk of money for working those routes when people were scared to leave their houses.

I thought she’d use it to fix up our old apartment or finally pay down the medical bills from my dad’s heart attack years before.

Instead, she told me she had already used most of it on “something important.”

She wouldn’t say what.

I lost it.

I told her she was tired, reckless, always putting other people ahead of her own family.

I said some things I wish I could burn out of the air with my bare hands.

She just looked at me, eyes tired, and said, “One day you’ll understand, baby.

Sometimes you have to help the person in front of you, even if nobody else thinks it makes sense.”

We never really fixed that argument.

Then the virus caught up with her bus line, and everything became hospital gowns and waiting rooms and phone calls that dropped in the middle of the night.

So now, watching this stranger kneel at her grave like he carried his own secret with him, I felt that old anger tighten.

What if he was the reason she got sick?

What if he was one of those people who came on the bus coughing and yelling that everything was overblown?

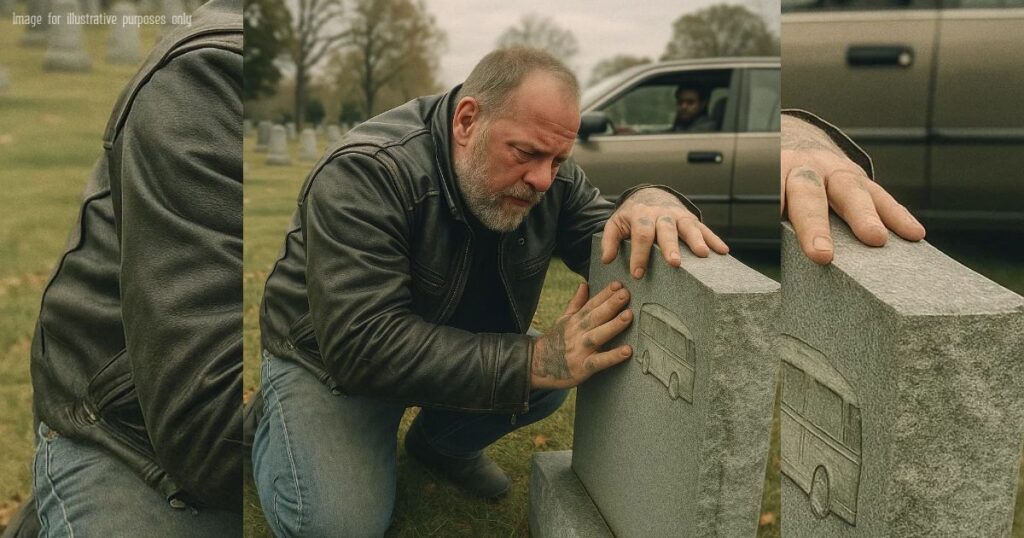

One Sunday in late fall, after almost a year of watching and imagining and letting my chest fill with questions, I saw his shoulders shaking.

He had one big hand flat against my mom’s headstone, fingers spread, like he was trying to hold on to something that was sliding away.

I couldn’t stay in the car anymore.

I opened the door, stepped out into the cold morning air, and walked across the damp grass toward them.

He heard me coming but didn’t move his hand.

He was a big man, easily six feet tall, with gray in his beard and deep creases around his eyes.

From a distance, he looked like every warning poster I’d grown up seeing about “stay away from trouble.”

Up close, I saw his eyes were red.

His voice, when he spoke, was quieter than I expected.

“Can I help you?” he asked.

“That’s my mom,” I said.

I pointed at the name on the stone, the dates, the tiny bus etched under them.

“Denise Carter.

I’m her son.

You’ve been here almost every week for a year and I don’t know who you are.”

He closed his eyes a moment, like he was sorting through words he wasn’t sure he had the right to use.

Then he stood up slowly, pulled his hand back from the stone, and looked at me as if he was asking permission just to breathe.

“I’m Hank,” he said.

“I didn’t mean to upset you.

I just… I needed to say thank you.”

“Thank you for what?” I asked.

My voice came out sharper than I meant, the way it does when you’re trying not to cry.

He glanced at the little bus carved under my mom’s name.

“Your mom saved my son’s life,” he said.

“I come here to tell her he’s still alive.”

I stared at him.

My mother drove a bus.

She wasn’t a surgeon or a specialist.

She never even finished college.

“What are you talking about?” I said.

“She was just a bus driver.”

“Nothing ‘just’ about it,” Hank said.

“Can I tell you the story?

You don’t have to stay.

But you should know.”

I didn’t trust myself to talk, so I nodded.

We both sat down right there in the grass, one on each side of the stone, like two kids about to share a secret we weren’t supposed to repeat.

“Seven years ago,” Hank started, “my boy Tyler was seventeen and hanging on by a thread.”

He told me about the factory closing where he’d worked since he was nineteen.

He told me about the back injury that came with the severance, the pills that came with the injury, and the way those pills felt like the only thing that still listened when the rest of his world stopped.

Click the button below to read the next part of the story.⏬⏬