“Tyler started sneaking some of mine,” Hank said.

“At first I told myself he was just curious.

Then the prescriptions dried up, but what we needed didn’t.

We started buying stuff that didn’t come in orange bottles anymore.”

He rubbed his face with both hands, like the memory itself hurt his skin.

“One night in January, cold enough that your breath felt like glass, Tyler got on your mom’s bus.

He never made it to the back of the line.”

Tyler dropped in the aisle, Hank said.

Just folded like a card table, eyes half open, lips going pale.

Other passengers shouted, some backed away, some filmed, some muttered about “kids these days” and “this is what happens.”

“Your mom pulled that bus over so fast people nearly fell out of their seats,” Hank said, and I could hear the pride in his voice, like he’d been there and seen it with his own eyes.

“She hit the emergency lights, got down on her knees in that uniform, and she didn’t ask him what he’d taken.

She asked him what his name was.”

He told me how she called for help, how she kept talking to Tyler even when he didn’t answer, how she told the rest of the passengers that if they were late to work that day, they could blame her, because nobody was going anywhere until she knew that boy was taken care of.

“The paramedics wanted to just take him to the nearest place and drop him in a hallway,” Hank said.

“They had too many calls, not enough beds.

Your mom argued with them like he was her own kid.”

He said she followed the stretcher down to the doors, insisting they take Tyler to the hospital that still had a real treatment unit.

She kept saying, “He’s somebody’s baby.

You don’t quit on somebody’s baby.”

Hank got a call from a number he didn’t recognize.

By the time he reached the hospital, Tyler was hooked up to machines, a nurse was explaining words like “overdose” and “respiratory failure,” and Hank was staring at his own reflection in the glass, wondering how many choices it took to end up right there.

“I saw your mom in the hallway,” he said.

“Out of uniform, just a woman with tired eyes and a coffee she wasn’t drinking.

She looked at me like she knew exactly who I was before I opened my mouth.”

He said he tried to apologize for his son, for himself, for everything.

He said she listened, really listened, without flinching, without acting scared of the big man with the shaky hands.

“She told me I wasn’t a lost cause,” he said.

“She said sometimes people stumble into your bus and you have a choice — pretend you don’t see, or help them sit back up.”

When the doctors told Hank about rehab options, they talked about waiting lists and costs.

The kind of numbers that make your chest tighten.

The sort of programs that sound great in theory but might as well be on the moon when you’re counting crumpled bills on your kitchen table.

“I almost walked away,” he admitted.

“I thought, ‘We’ll never afford this.

We’ll try to do it at home.’

But then I remembered your mom’s face.

I remembered how furious she got with those paramedics.”

A week later, Hank got a call from a treatment center across town.

Tyler had been accepted into a program, they said.

The first month was already paid by “a community fund.”

“I thought it was some miracle I didn’t deserve,” Hank said.

“Then, a few days after that, I got an envelope in the mail.

No return address.

Just a note that said, ‘First steps matter most.

Let him take them.’

And there was cash inside.

Enough to keep him in treatment.”

He tried to find out who had sent it, but the hospital wouldn’t say.

The bus company said they had some kind of informal fund, but nobody would give him names.

Life, as it does, started moving in other directions.

“Tyler got clean,” Hank said.

“He slipped a few times, but he got up more times than he fell.

We argued.

We made up.

We went to meetings together.

It wasn’t perfect, but it was life, and we still had it.”

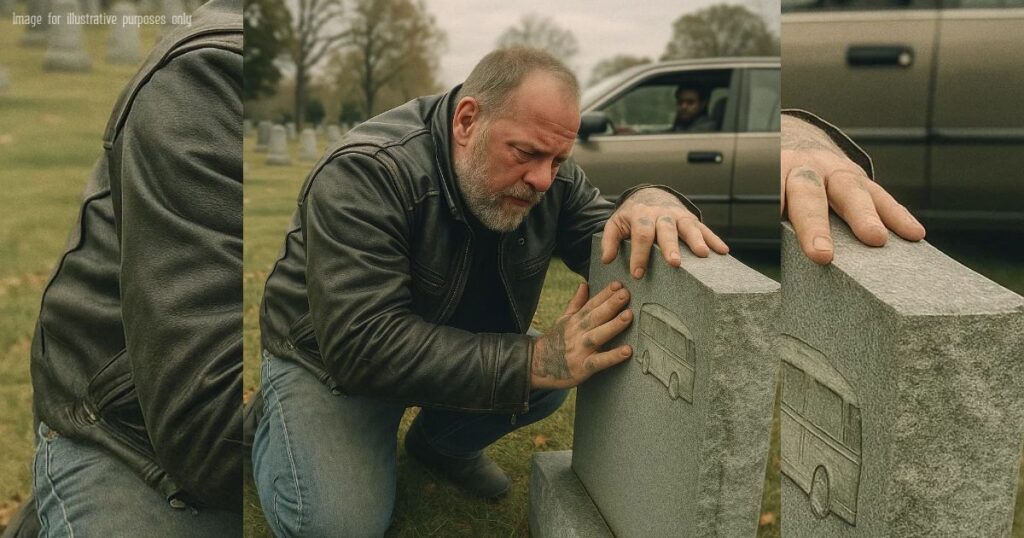

He paused, looked down at the carved bus under my mom’s name again.

“Then the virus came,” he said.

He told me about working odd jobs, about friends getting sick, about watching people on television argue about who was overreacting and who wasn’t doing enough while the nurses and drivers and clerks just kept going to work because someone had to keep the lights on.

“One night, I was sitting on the couch with Tyler,” Hank said.

“The news was playing a little segment about folks who had died doing their jobs.

Faces of nurses, grocery clerks, drivers.

And suddenly there she was.

Your mom.”

They showed her in her uniform, eyes crinkled above her mask.

They called her “a dedicated public servant,” mentioned that she got sick after working long hours on crowded routes.

Tyler sat up straight, pointed at the screen, and said, “That’s her.

That’s the bus driver.

Dad, that’s the woman who pulled me off the floor.”

Hank said it felt like someone reached inside his chest and squeezed.

All the years he’d meant to say thank you and never had.

All the Sundays he’d spent polishing his bike instead of looking up her name.

Gone.

“I started making calls,” he said.

“Bus company.

Union office.

The church that held a tiny service for her.

Finally someone told me where she was buried.”

He cleared his throat, eyes shining.

“I couldn’t go to the funeral.

I couldn’t rewind time and say what I should have said in that hallway.

So I started coming here instead.”

While he talked, the cold seeped through my jeans, and my brain kept going back to that fight about the hazard pay money.

My mom’s tired voice saying “something important.”

My own angry words bouncing off the walls of our kitchen.

Click the button below to read the next part of the story.⏬⏬