Part 2 — The day after I “resuscitated” myself, my daughter arrived with a conservatorship petition…and watched me resuscitate a stranger.

Dawn broke the way good coffee does—dark first, then forgiving.

I was already at the grill, wrists aching, the steel hissing like rain on a summer road.

The bell over the door made that thin, hopeful sound I have begun to live for.

Alex came in with the steady, stunned look of a person who slept.

“Morning, Boss.”

“Apron,” I said. “And salt the tomatoes this time. They are not decoration; they are intervention.”

I checked my phone.

A text from Jessica: Landing at nine. Coming with counsel. Please be ready to cooperate.

Counsel.

Of course.

I wrote the day’s special on the chalkboard with my terrible, decisive handwriting:

CHICKEN SOUP • REAL COFFEE • DROWNING HOUR 12–2 (QUIET TABLES, NO LAPTOPS, CRYING WELCOME).

Walt shuffled in, denture line tugging at his mouth like a bad stitch.

“Oatmeal,” I said, already ladling.

He pretended to scowl, then tapped the table twice—veteran for thank you.

We are developing a language here.

Eye-rolls, refills, the angle of a plate—tiny signals that say, you’re seen.

At nine-fifteen, the door opened and a breeze made the napkin dispenser sigh.

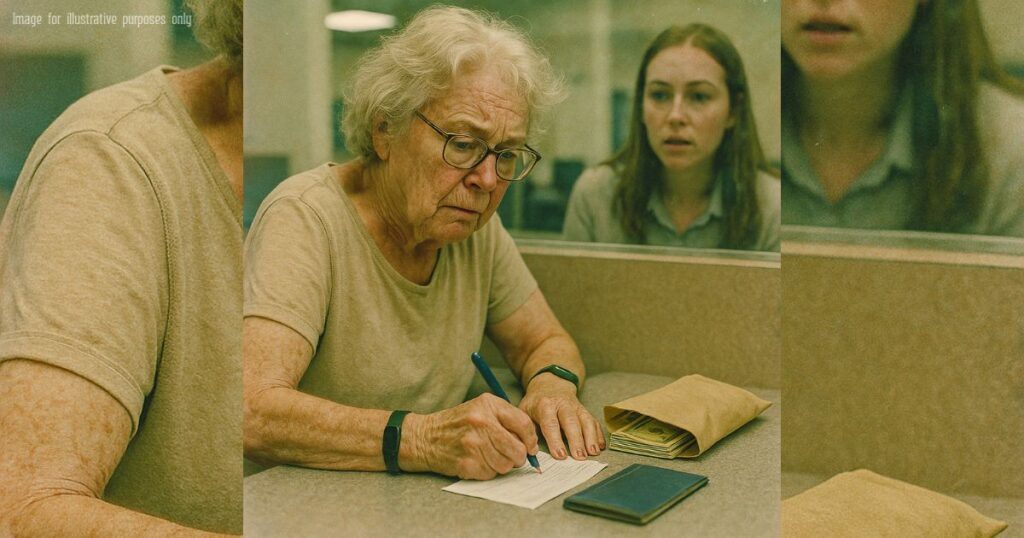

Jessica walked in with a man in a navy suit who looked like he ironed his sleep.

Her hair was pulled tight enough to hurt my own scalp.

“Mother,” she said.

The suit placed a folder on the counter.

“Ms. Adler,” he began, “good morning. I’m—”

“I know exactly who you are,” I said, and turned down the flame under the onions.

“Can this wait three minutes? The grill is a jealous god.”

It could not, apparently.

He opened the folder and spoke about capacity and protection and the “dissipation of assets.”

He used the phrase “undue influence” and looked at Alex as if compassion were a scam.

“Do you smell that?” I asked him.

He paused. “Smell what?”

“The onions,” I said. “They’re about to burn. Which is what happens when you ignore the thing in front of you for the idea in your head.”

He blinked.

I rescued the onions.

The bell rang again and the diner filled fast—strollers, paint-stained carpenters, a woman in scrubs rubbing her temples with two fingers like she was trying to erase a day that hadn’t started.

Jessica’s face softened, then steeled.

“Mom, sit with us,” she said, guiding me toward a booth as if I were an IV pole.

“Five minutes,” I said. “Then I go back on the line. I am short-staffed in the soul department.”

We sat.

Mr. Navy unfolded words like wires.

Temporary orders. Medical evaluation. Freezing accounts. Protecting me from me.

Jessica watched me with the brittle love of someone sure she is doing the right thing.

“Jessica,” I said, “conservatorship is for incapacity, not inconvenience.”

She flinched.

“So you’ll take a cognitive exam?” she shot back. “Here? Now?”

“If we must,” I said. “But you should know my favorite trick is solving problems you can’t list on a form.”

A plate clinked somewhere.

The room shifted.

A delivery driver at the counter—late twenties, sweat salt-mapping his T-shirt—swayed, then folded like a bad tent.

Time slowed the way it does when life demands you shut up and move.

“Alex, call 911,” I said, already crossing the room.

“Sir—hey—look at me,” I said to the young man on the tiles.

His eyes rolled; his chest went tight and useless.

Here is the thing about being a nurse for forty-five years.

Your body remembers what your mind doesn’t have time to narrate.

I cleared the space around him, heard my own voice from far away—calm, not kind.

“You,” I told a kid near the napkin holder, “prop the door. You,” to a carpenter, “watch the sidewalk for the ambulance and wave them in like you’re guiding a plane.”

I found the sternum with the heel of my hand.

I did what my hands were shaped by work to do.

No lecture. No heroism.

A rhythm older than language.

Jessica stood frozen at the edge of the circle, her lawyer a ghost beside her.

“Glove up or get out,” I said without looking.

My daughter moved.

She pulled on food-service gloves with shaking fingers and counted out loud the way I taught interns who were terrified of time.

Sirens.

Boots.

The paramedics burst in, quick and sunburned, sweat shining like lacquer on their foreheads.

“Ruth?” one of them said, startled into a grin. “You’re supposed to be retired.”

“Then take over,” I said, and they did, with the tidy violence of people who refuse to lose if a heartbeat can be bullied back.

They loaded him.

He blinked once at me, confused, stubbornly alive.

“Soup’s on me when you’re back,” I told him, and he gave the smallest nod a person can give without breaking the band that ties them to the world.

The room exhaled all at once.

I stood, wiped my palms on my apron, and the diner applauded the way people clap at landings: grateful, frightened, astonishingly human.

I turned to Jessica.

“Now,” I said. “Paperwork?”

We went to the alley where the air was wet bread and rain.

She had lost an inch of height, or maybe it was the weight rolling off the stories she tells herself.

“You could have gotten hurt,” she said softly. “You’re seventy-two.”

“My joints are loud,” I said. “I’m not a vase.”

Her lawyer cleared his throat.

“Ms. Adler, the concern is not only physical risk. It’s financial. You cashed out everything for a failing business.”

“Correct,” I said. “I traded interest for purpose. My ROI is measured in pulse and pie.”

He did not laugh.

I did not expect him to.

Jessica leaned against the brick and slid down until her expensive jacket met the alley floor.

“I’m trying to save you,” she said to her knees.

“I know,” I said.

“But if your version of saving requires taking my keys, my calendar, and my pride, that is not care. That is custody.”

She looked up, eyes full and fierce.

“And if you fall? If you lose everything? If you die behind that counter?”

I stepped closer.

“Then I will have died in my station with my name on my own chart.”

She closed her eyes.

For once, she didn’t have a spreadsheet between her and the world.

Only the world.

Here is the controversial truth, and I will say it plain because I have earned plain speech:

Safety is not the highest human good.

Meaning is.

You may disagree. Write your think pieces.

But many of us are not dying from danger; we are dying from being padded and parked until we forget our names.

I went back in and flipped the chalkboard to the other side.

In big, unforgivable letters I wrote:

THIS IS NOT AN EFFICIENT PLACE. THIS IS A USEFUL ONE.

At noon, Drowning Hour began.

Chloe came with the baby, hair unwashed, hope fragile as tissue.

Two other mothers followed, then a grandfather with twin toddlers who were determined to test the tensile strength of napkins.

We cleared the corner booth.

No laptops.

No shame.

It got loud in the way that heals, a clatter of need and the soft thunder of answers that are not solutions, just presence.

Jessica watched from a stool.

I saw the moment something gave.

She reached into her bag, pulled out her tablet, then hesitated, then put it away.

She stood and, clumsy as kindness on a first day, picked up a tray.

“Where do you want me?” she asked.

“Table six,” I said. “The construction crew. They look mean but they tip like saints if you remember extra napkins.”

She went.

She listened.

She learned the choreography ordinary people do every day without a slide deck.

A woman in scrubs told her about twelve-hour shifts and the way grief smells.

A teen asked if she could feel her baby kick.

A carpenter cried into his chili and called it the weather.

Click the button below to read the next part of the story.⏬⏬