The man who slammed his fist on my counter wasn’t a monster; he was a father, watching his daughter fade away in the parking lot over the price of a single vial.

I’m an ER nurse. Forty-five years old, twenty years on the job, and I’ve seen it all. You think the graveyard shift at a convenience store is rough? Try a Tuesday night in a downtown public hospital, where the overdoses, the knife wounds, and the sheer desperation are just part of the paperwork.

The air conditioner was broken again, making the whole place smell like bleach, old coffee, and a metallic tang I’ve come to associate with blood. I was on hour ten of a twelve-hour shift. My feet were screaming, my back ached, and my patience was a thin, frayed thread.

Dr. Matthews, our resident in charge, was already burned out at twenty-eight. He was barking orders, more focused on the charts and “patient throughput” than the actual people. We were full. Every bed was taken, and the waiting room was a sea of coughing, misery, and quiet despair.

That’s when the doors slid open. Not with the polite whoosh of a worried family, but with a bang, as if they’d been kicked. The cold, rainy November air blasted in, and so did he.

He was huge. Not just tall, but built like the side of a truck. He was easily six-foot-four, dripping wet, with a thick black beard and tattoos covering his neck and knuckles. He wore a heavy leather vest, the kind with patches I couldn’t read, except for a faded American flag and a “Semper Fi” crest on his shoulder.

He didn’t walk to the desk. He stalked. His boots, heavy and wet, slammed on the linoleum with a purpose that made everyone in the waiting room fall silent. The coughs stopped. The crying baby paused.

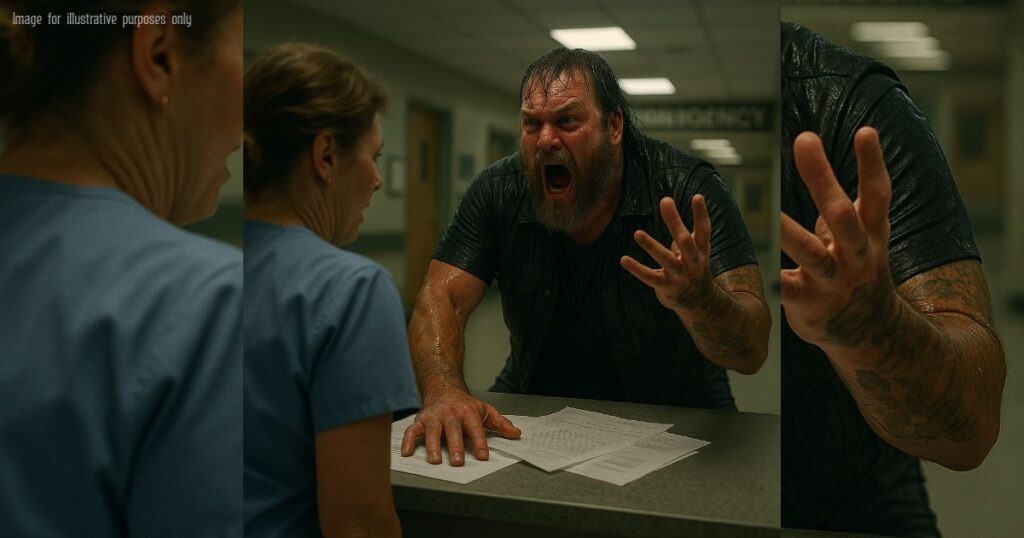

“I need help,” he yelled, his voice a raw gravel that cut through the beeping monitors. He bypassed the entire line, the twenty sick people waiting to be triaged, and slammed a massive, tattooed fist on my intake counter. The plastic barrier rattled. The cup of pens jumped.

I recoiled. Not because I was scared. I wasn’t. I was just tired. Tired of this. Tired of the yelling, the entitlement, the violence that bubbled just under the surface of every night.

“Sir, you need to step back,” I said, my voice flat, robotic. This is the voice I use when I’m dealing with a threat. “You have to wait in line like everyone else. I need to take your information.”

“I don’t have time!” he roared. His eyes were wide, frantic, and bloodshot. “I don’t have time for your goddamn line! I need medicine!”

Of course he did. At this time of night, “I need medicine” almost always meant one thing. He was a user, deep in withdrawal, and he was getting aggressive.

Frank, our night shift security guard, a good man but one who’d rather use his muscle than his words, unclipped the strap on his holster. “Sir, I’m going to ask you one more time to lower your voice and step away from the nurse’s station.”

“You don’t understand!” the biker shouted, his eyes darting around, looking for… something. “She’s out in the truck. She’s fading. Please!”

“He’s probably high,” Dr. Matthews muttered from behind me, not even looking up from his tablet. “Frank, just get him out of here. Call the police if you have to. We don’t have time for this.”

“She’s my daughter!” the man screamed, and this time, his voice broke. It cracked open, and all the rage leaked out, replaced by something I knew all too well. Pure, uncut terror.

“She’s my daughter,” he repeated, his voice dropping to a desperate whisper. “Her name is Lily. She’s eight. Please. I just need one vial. One. I have money.”

He fumbled in the pocket of his wet jeans, his huge, shaking hands pulling out a crumpled wad of bills. He threw it on the counter. “It’s all I have. It’s five hundred dollars. I know it’s not enough. I know what you charge. But please, just take it. It’s all I have.”

Frank was moving in. “Sir, if you’re not leaving…”

“I can’t!” the man sobbed. He was crying now. Big, ugly sobs that shook his entire body. This giant of a man, this leather-clad warrior, was disintegrating in front of us.

With the money, something else had come out of his pocket. It fell from the wad of cash, a small piece of dark metal on a blue ribbon. It skidded across the counter and came to a stop right in front of my keyboard.

I’d seen one before. My grandfather had one in a dusty box on his mantelpiece. It was a Purple Heart.

My hand, acting on its own, reached out and touched the cold metal. I looked up from the medal and into his eyes. I mean, I really looked at him for the first time.

He wasn’t a threat. He wasn’t a drug user. He was a father. And he was watching his child die.

“Frank,” I said, my voice sharp, cutting through the man’s sobs. “Stop. Stand down. Both of you.”

I looked at Frank, who was confused, and then at Dr. Matthews, who was annoyed. “I’m handling this. Give me a minute.”

I turned back to the man. His head was in his hands, his shoulders shaking. “What’s your name?” I asked, my voice softer now. The “ER nurse” voice was gone. This was the “mom” voice.

“Reb,” he choked out from behind his hands. “My name is Reb. Please. My Lily. She’s Type 1. Her pump failed. The new one… it’s not working. Her blood sugar… it’s high. Too high. She’s in ketoacidosis. I can smell it on her breath.”

I knew that smell. Sweet, like rotting fruit. A sign of impending death. This man, this biker, he knew the medical term. He knew the smell. He was no fool.

“Why didn’t you bring her in?” I asked, keeping my voice calm.

“I tried!” he said, looking up, his face a mask of anguish. “She’s… she’s not conscious. I picked her up to carry her, and she started seizing. I was afraid… I was afraid moving her would make it worse. I just live… I live six blocks from here. I thought I could run here, get the vial, and run back. It would be faster. Please.”

“Reb, I can’t just give you insulin,” I said gently. “Even with money. It’s a prescription. It’s the law. The only way is to bring her here. In an ambulance.”

“I can’t call an ambulance!” he snapped, his frustration boiling over again.

“Do you know what that costs? That’s a five-thousand-dollar ride we can’t afford! And then we get here, and you’ll charge me nine hundred dollars for a vial that costs you three. I know the game. I just… I can’t play it tonight. I can’t.”

He pointed a shaking finger at the Purple Heart on the counter.

“I got that in Fallujah. I took three bullets to the chest for this country. I came home. I worked. I tried to do everything right. And now… now my daughter is dying in a beat-up truck because I can’t afford the medicine to keep her alive.”

His story came tumbling out, the words of a man pushed past his limit.

His wife worked part-time as a cashier. He was a mechanic, a gig worker, no benefits. Their cheap insurance plan had just “updated its formulary” last month.

“They won’t cover her brand anymore,” he said, his voice hollow.

“They switched to a new one, a ‘preferred’ brand. We tried it. Lily had a bad reaction. She broke out in hives. Her doctor said she can’t take it. But the insurance company… they won’t make an exception. They said we have to ‘appeal.'”

He laughed, a bitter, broken sound.

“Appeal. While my daughter dies. So we have to pay out of pocket. Nine hundred and forty dollars for one vial. That’s more than I make in a week. We’ve been rationing it, Reb. Rationing. Trying to make it last until my VA benefits… maybe… kick in. But the paperwork is stalled. It’s been stalled for a year.”

He was right. I knew the price. I saw it on patient bills every single day. A vial of liquid life, marked up three thousand percent.

I looked at Dr. Matthews. “Doctor, we have a pediatric emergency in the parking lot.”

Matthews sighed, annoyed at the interruption.

“Sarah, I told you. Tell him to call 911. Or bring her in. Those are the rules. If we start handing out drugs in the parking lot…”

“He’s a veteran,” I said, my voice low and cold.

“And? This isn’t a VA hospital.

I have thirty patients in this room, and I’m the only doctor. My hands are tied.” He was looking at his chart, not at the man.

My hands are tied. The anthem of a broken system.

I felt something snap inside me.

Twenty years of seeing this.

Twenty years of watching people fall through the cracks. The cracks were canyons now.

I had a choice. I could follow the rules, protect my job, and listen to this burned-out resident.

I could let Frank haul this broken man to jail and let whatever happened to Lily, happen.

Or I could be a nurse.

“Reb,” I said. “Where is your truck?”

He looked at me, confused. “It’s… it’s right by the door. In the ambulance bay. I know I’m not supposed to be there…”

“I’ll be right back,” I said.

Continue Reading 📘 Part 2 …