Two hours before dawn on the third night of the blackout, they tore through my house with flashlights and latex gloves while my twelve-year-old daughter had been missing for sixty hours, and I followed a paper snowflake and the sound of a bell. The city was boiling, the grid was failing, and every stranger’s phone pointed at me like a verdict I hadn’t earned.

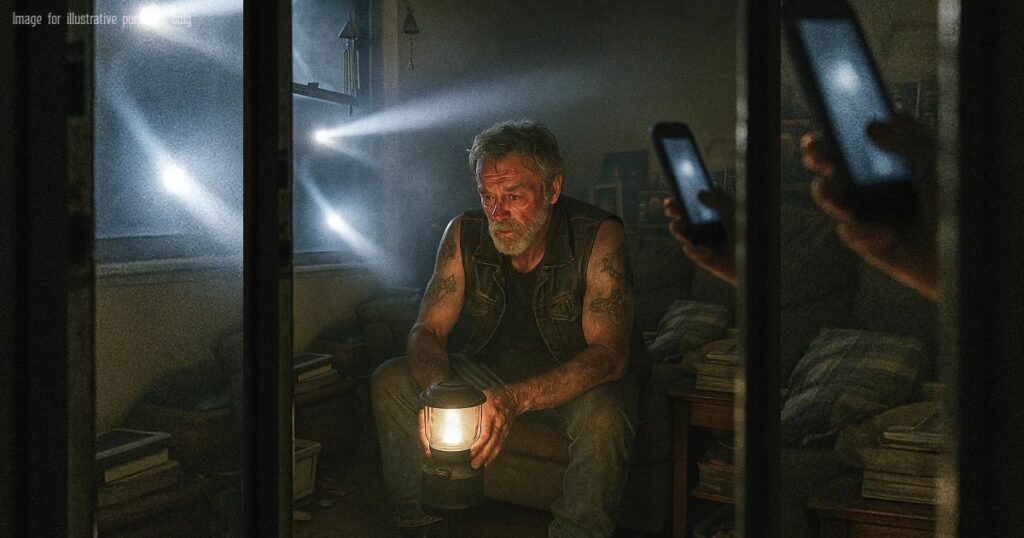

I’m James “Bear” Salazar, sixty-seven, a biker who’s been on two wheels longer than most reporters have been alive. I wear a leather vest that smells like rain and road, and I have a voice that sounds like gravel when I haven’t slept, which I hadn’t, not since Rosie slipped out of a world I thought I’d made safe for her.

Rosie is autistic and doesn’t speak, but she is not silent. She talks in patterns and echoes, in the slick whirr of a box fan, the numbers on bus routes, the bright promise of a snowflake symbol taped to city windows that means “cooling center.” She has always understood heat as a problem and bells as a map.

The night she vanished, the power had blinked out twice already. I lit the kitchen with a camping lantern, arranged applesauce cups the way Rosie likes—edges lined, labels facing, nothing touching—and stepped onto the back porch to feel the air for storm or relief, but the wind was like breath from an oven.

The gate was locked. The wind chime I made for Rosie—thin shells and a silver bell—clicked once and went still. Her shoes sat by the back door in their patient little way, toes slightly inward like they were waiting for permission to be feet again.

I searched every room, then the shed, then the hedges with my flashlight clenched between my teeth.

I knocked on the neighbor’s door and on the next neighbor’s door, and when the minutes kept stacking into danger, I punched in the emergency number with hands that wouldn’t hold still.

Forty minutes after I last saw Rosie, I was on with the dispatcher, and I could already hear in my own voice the kind of guilt people love to amplify.

They came fast. Officers in vests, a detective with a notepad, the neighbor across the street going live on her phone because every neighborhood has someone who thinks a broadcast will buy the truth a bus ticket.

“Why did you wait?” the detective asked, and I said, “Because I searched,” and he wrote something that made the line of his mouth look satisfied.

They shone lights across my new patch of concrete near the back steps.

They thumped it like a door they meant to kick in, and someone whispered, as if grief had a shape you could pour and hide.

“It’s a ramp,” I said, “for Mrs. Ramirez next door, her knees are shot,” and I showed the receipt in the drawer, the level and trowel still gritty with work.

The dogs had trouble in the heat.

Scent lifted and frayed and went nowhere.

The detective frowned at the wind like it had taken a side.

He asked about Rosie’s mother, and I said she died when Rosie was a baby, and I saw him mark my loss down as motive, like sorrow had an angle.

CPS knocked before midnight.

The worker was sunburned and apologetic and carried a folder fat with duplicate forms.

She said the city was doing rolling wellness checks during the blackouts, especially for families like mine, and I said, families like mine means what, exactly, and she said, carefully, families with extra needs.

My club showed up with cold water and quiet eyes.

They offered to fan out on their bikes and cover the grid like a quilt of engines and headlamps, but the detective said it was an active investigation and to let first responders do their jobs. I saw the way he looked at my vest patches and tattoos, the way people mistake surface for core.

At 2 a.m., a young officer named Jones jogged back from a canvass with a gas station clerk’s printout of camera stills.

Grainy images, time stamps blurred by heat, and in one of them a small figure in a blue T-shirt passed under a floodlight, bare feet pale as peeled paint.

Rosie held a folded flyer against her chest like a compass.

They zoomed the flyer until the pixels bled. In the middle of it, a blue snowflake took shape, the city’s cooling symbol, the mark taped on library doors and community centers offering water and air when the grid surrendered.

Someone said, she’s seeking shade, and someone else said, or she’s following a picture because pictures are easier than words.

“Let me ride,” I said, and Detective Hale nodded once.

Her eyes were tired but not unkind.

She told me to stay where she could see me, and I said, you can’t miss me, I’m the one who looks like trouble and is not.

We followed the line of snowflakes like stars.

Library. Closed early, staff sent home when the power failed. Church hall.

Packed, then emptied when the generator coughed its last.

A community gym where volunteers handed out water until the pallets ran dry.

Everywhere, the same symbol, taped to glass, curling at the edges in the heat.

Rosie’s language is loops and returns.

When she was little, she would trace the same city blocks until cracks in the sidewalk felt like friends.

When I saw bus route numbers posted in a cooling center—7, 12, 22—I thought of the way she taps those numbers against her leg like a rhythm only she hears. I wrote them down in grease pencil on my tank.

We hit a bus depot and a driver let us scrub through the camera feed.

At 4:12 p.m. yesterday, Rosie turned left off the 12, crossed in front of a parked bus, and disappeared toward the medical district.

She moved with purpose, not lost. She carried the flyer. She checked street signs without reading them, the way she always does, like signs are for other people but direction is hers.

The medical district had grown strange since the last time I’d dared its hallways.

The big hospital had absorbed the smaller one.

The old maternity building stood emptied, its doors chained but not loved, and the chapel’s stained glass wore a thin coat of dust. An EXIT sign flickered like a green heartbeat.

I hadn’t talked about the small plaque in that chapel with anyone but a priest and the wind.

When Rosie was born, she had a twin. He didn’t make it past the first night.

The hospital let us choose a brief inscription on a communal memorial, and I chose Baby Salazar, because I was out of words that day and have been trying to earn them back ever since.

We circled the building while the sun convinced the asphalt to steam.

A maintenance van idled near a side entrance, driver waving a clip board like a truce flag.

“That door,” he said, “sticks sometimes, doesn’t latch,” and his voice carried the exhausted kindness of a person who spends his life fixing what fails.

Detective Hale sent in two officers and a medic.

I asked if I could go and she said, if we find anything, you’ll know in less than a second the way you know what time it is without a clock.

I gripped the handlebars until the bell on my brake cable chimed against metal and made a small sound that broke me.

Continue Reading 📘 Part 2 …