Part 4 – Back When Work Meant Something

We didn’t call it “burnout” back then. You just kept showing up, even when your hands bled and your back screamed — because animals were waiting, and that was that.

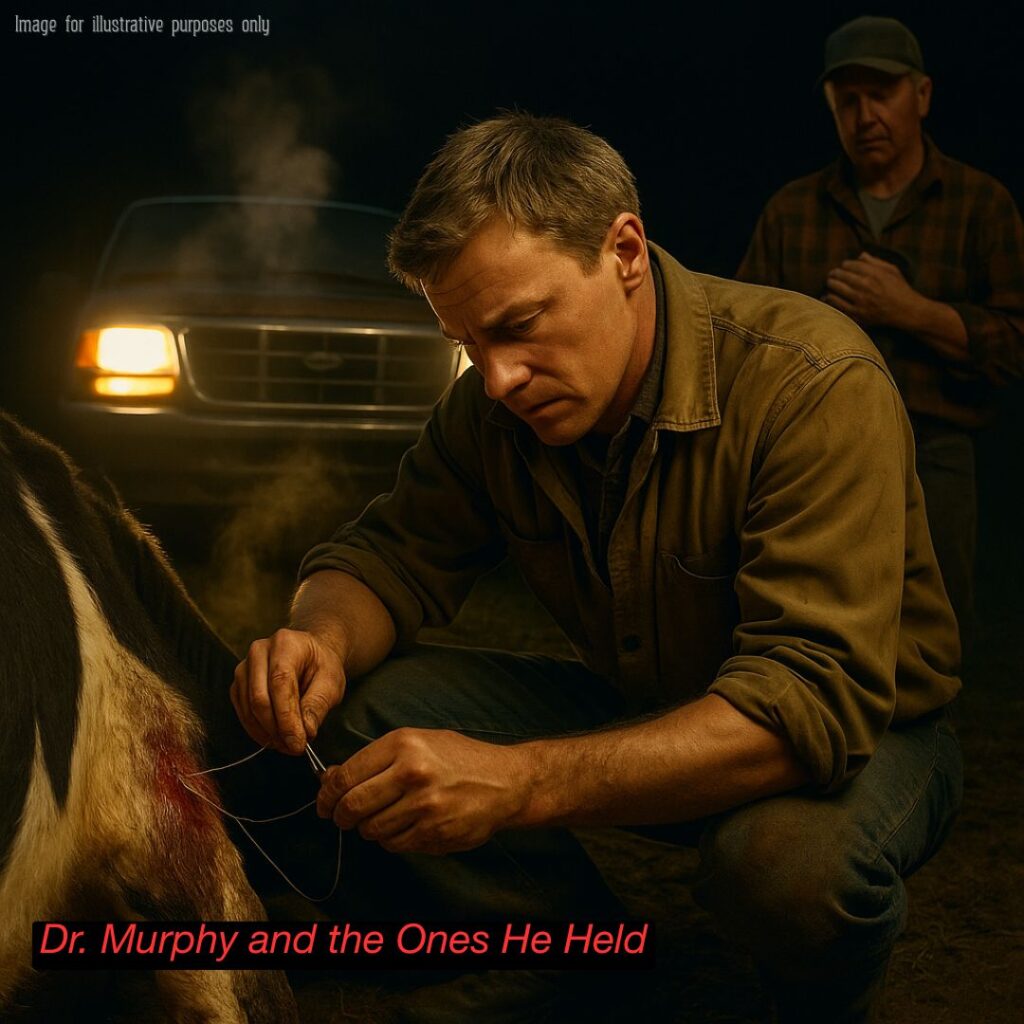

In 1991, I stitched up a cow at 3 a.m. by the light of a Dodge Ram’s headlights and the prayers of a farmer named Earl McKinley.

Earl’s place sat just past the county line, where the pavement gave up and the dirt road made your teeth rattle. The cow had caught her flank on rusted fencing, deep enough to see the muscle twitch. Earl was in tears, holding his cap in both hands like it was a Bible. Said it was the only milk cow his family had left. Said if she didn’t make it, neither would they.

I was twenty-eight. My back hurt from hauling hay that morning. I’d eaten a gas station sandwich for dinner and was running on fumes and stubbornness.

But I got her stitched.

Not perfect. Not pretty. But she lived. And two weeks later, Earl brought me a slab of smoked brisket wrapped in foil and said, “You saved my wife’s kitchen table.”

That’s what work used to be.

It wasn’t about prestige. Or comfort. Or apps. It was about showing up when it mattered — and knowing that doing your job right might just hold a family together one more season.

I grew up around men who worked with their hands.

My father built barns. My grandfather fixed railroad engines. My uncles were mechanics, roofers, truckers, welders — blue collars worn thin and faded like flags over long winters.

None of them went to therapy. They drank black coffee, lit Marlboros, and kept their pain tucked behind the same jokes they’d been telling since Eisenhower.

They believed in work. Not as an identity, but as a duty. Something you owed to the people who trusted you.

I remember one summer — ’74 maybe — I worked for an old vet named Dr. Harmon. I was just a kid then, mostly mucking stalls and cleaning kennels. He paid me in cash and Coca-Cola.

He had a white coat that never stayed clean and a file cabinet full of notes written in his own shorthand. No receptionist, no computer. Just him, a stethoscope, and a pickup with rust eating through the tailgate.

One day, a man came in with a coonhound wheezing so hard you could hear it from the parking lot. The dog had gotten into some rat poison.

Dr. Harmon didn’t ask for insurance. Didn’t pull out a clipboard. He looked the man in the eye and said, “You love him?”

The man nodded, already crying.

“Then help me hold him,” Harmon said.

That was it.

We pumped his stomach. Gave him charcoal. Prayed harder than any church service ever required.

The dog lived.

The man came back two weeks later with a bushel of apples and said, “You saved my boy.”

I asked Dr. Harmon later, “Why’d you do it for free?”

He looked at me, wiped his glasses on his shirt, and said, “Because that man didn’t come here for a transaction. He came here for help. You help where you can, son. Always.”

When I opened my first clinic in the mid-’80s, I tried to carry that with me.

Didn’t matter if it was a barn cat or a prized stud. If they needed care, I did my best to give it. Even if the check bounced. Even if the thank-you never came.

Because back then, work had weight. It wasn’t about productivity metrics or quarterly goals. It was about whether the person across from you could sleep a little easier that night because of something you did.

And that was enough.

Now?

Now I’ve got corporate reps telling me to upsell dietary plans and bundle preventive packages like I’m a damn car salesman. Got folks asking for second opinions from TikTok before I can even get the stethoscope around their dog’s neck.

Last month, a woman asked if I could email her the euthanasia procedure in advance so she could “emotionally prepare.”

I said no.

Because some things should never be done through a screen.

But sometimes, late at night, when the clinic’s dark and the only sound is the hum of the old fridge in the break room, I take out my ledger.

Not the billing one. The real one.

The one with names, not numbers.

It’s an old spiral notebook with grease stains and dog hair pressed between the pages.

It’s got scribbled entries like:

“Jake – hound mix – found tied to a tractor tire – healed.”

“Missy – farm cat – fractured pelvis – owner brought eggs every Saturday for a year.”

“Earl McKinley – milk cow – brisket.”

There’s no algorithm for that.

No metric.

Just memory.

And meaning.

They call it nostalgia now, like it’s some weakness. Like remembering the good old days is clinging to a world that’s gone.

Maybe it is.

But I don’t miss the pain. Or the poverty. Or the endless hours without sleep.

I miss what work meant.

I miss the look in a man’s eyes when you handed him back his dog alive, and he didn’t have the words, so he just shook your hand with everything he had.

I miss kids drawing crayon thank-you notes and taping them to the fridge.

I miss smokehouse payments and late-night calls that ended with coffee on a tailgate and silence shared like scripture.

You don’t get that kind of work from behind a desk.

You get it when your knees hit the dirt.

When your fingers fumble in the dark for a pulse.

When your breath fogs up a barn window in February and you keep going anyway.

Chet — or Soldier, as I learned — still waits on the porch most mornings.

He watches the young techs come and go. Watches the delivery guys drop off their sterile boxes of pre-filled vials.

Sometimes I swear he’s judging them.

Sometimes I swear he’s judging me.

And maybe he should.

Because I used to work with my gut, not a tablet.

Used to feel a heartbeat and know what was coming before the machines ever beeped.

Used to trust my hands.

One of my young assistants asked me last week why I still use that dented exam table.

I told her, “Because it remembers things I don’t.”

She didn’t get it.

Maybe someday she will.

ENDING TRUTH:

Work used to mean something.

It wasn’t who you were — it was how you showed up.

Not for praise. Not for perks.

But because someone needed you.

And that was reason enough to stay.