Part 6 – The Boy Who Wouldn’t Let Go

He walked into my clinic carrying a shoebox with both arms like it was the crown jewels — and he cried if anyone else tried to touch it.

It was August, 2003.

Hot enough to make the air feel like soup. The kind of summer that melts tar between the gravel and sends cicadas screaming in your ears all day. I was halfway through suturing a torn ear on a Labrador when the door chimed.

A boy came in.

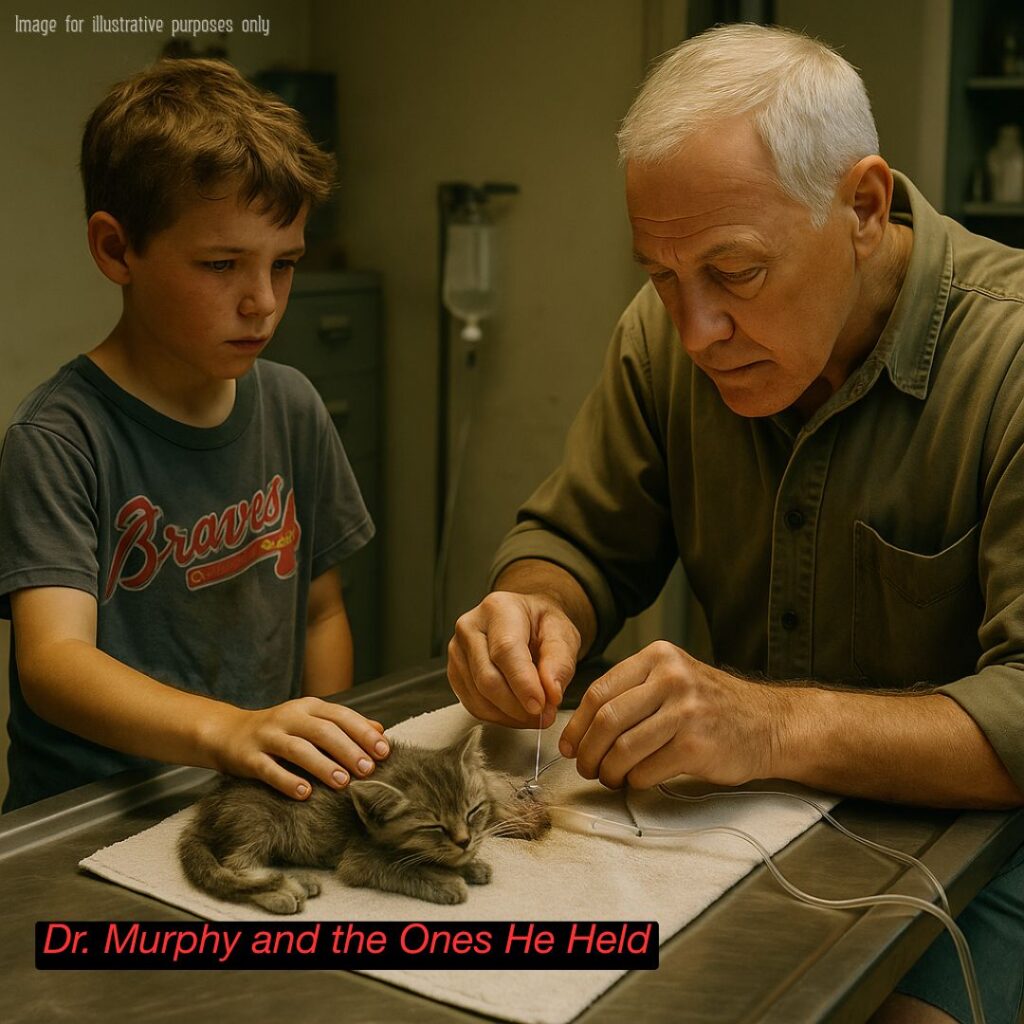

Couldn’t have been more than nine. Barefoot, hair plastered to his forehead with sweat, freckles across the bridge of his nose. He wore a faded Atlanta Braves shirt and the kind of serious face you don’t usually see on children unless they’ve had to grow up too quick.

In his arms: a battered Nike shoebox, both hands gripping the edges so tight his knuckles went white.

Behind him, no parent. No older sibling. Just him and the box.

I finished with the Lab as quick as I could and waved him over.

“What’ve you got there?” I asked.

He hesitated. Looked down. Swallowed hard.

“She’s hurt,” he said. “Real bad. But she’s still breathing. I can feel it.”

I lifted the lid.

Inside was a kitten. Small enough to fit in one palm, fur the color of wet ashes, eyes half-closed. Its breathing was shallow, chest stuttering every few seconds. One back leg hung at the wrong angle.

I could smell the infection before I saw it.

“Where’d you find her?”

“Behind the old Piggly Wiggly,” he said. “Some kids were throwing rocks. I made ‘em stop.”

His chin trembled, but his hands never loosened.

I told him we’d need to take her to the back, get her on the table.

He didn’t move.

“I’ll come,” he said. “She’s scared. She knows me.”

Most kids say things like that because they’re scared for themselves. This one said it like he was making a promise to her.

I let him follow.

We worked fast — oxygen, fluids, antibiotics. The leg was bad, but the infection was worse. If we didn’t treat it, she wouldn’t make the night.

I told him as much.

He nodded like he already knew.

“You can fix her,” he said. “You’re the animal doctor.”

Sometimes kids have that blind faith that could crush you if you thought about it too long.

While I worked, he stood on the other side of the table, one small hand resting just behind her head, where she could smell him.

He didn’t flinch at the smell. Or the needles. Or the blood.

He just kept whispering, “Hang on, girl. You hang on.”

After an hour, we had her cleaned, medicated, and stabilized. The leg… that was another conversation.

I told him it might need to come off. That she’d live, but she’d be different.

He shrugged.

“My grandpa’s only got one leg. He still beats me at horseshoes.”

That was the moment I knew — if this kitten lived, she had a home.

Problem was, the boy didn’t have much else.

No parent came looking that day. Or the day after.

Turns out he lived with his grandpa in a trailer outside town. His mom was “away,” and his dad was “nowhere,” and the old man got by on Social Security and odd jobs.

They didn’t have a carrier for the cat. They didn’t have food for her.

But they had him.

She stayed with us for a week.

Every morning before school, he came in on his bike, parked it right by the front window, and sat with her before the bell rang.

He’d read to her — not picture books, but whatever old Western paperback his grandpa had finished the night before. His voice was soft but steady, like he knew the sound mattered more than the words.

Every afternoon, he came straight back. Brought bits of chicken from his lunch tray. Once, a slice of bologna folded in half and tucked into his pocket.

On the eighth day, I told him she was ready to go home.

He grinned for the first time since I’d met him. Not a small grin. The kind that pushes up into your eyes and makes you forget you’ve ever been sad.

We wrapped her in a towel and placed her — still on three legs — back in that same battered shoebox.

He carried her out like he had the first day: both arms, tight grip, not trusting the world to be careful.

Two years later, I was sweeping the porch of the clinic when a tall kid came up the steps.

Took me a second to recognize him.

Same freckles, but taller now. Stronger. Clean ball cap pulled low.

“Hey, Doc,” he said. “Thought you might want to see her.”

He lifted the lid of a much newer box — not a shoebox this time, but a proper pet carrier.

Inside was that same gray cat. Sleek now. Bright-eyed. Hopped up on three legs like she’d never had any other number.

“She still beats me at everything,” he said.

I see a lot in this job. Broken bones. Broken animals. Broken people.

Not everything can be fixed.

But sometimes, it’s not about fixing.

It’s about holding on until the hurting part passes.

The boy — well, he’s a man now. Works construction. Comes in every couple of years with some scruffy rescue in his truck bed, looking sheepish but proud.

The cat lived a good, long while. Died at seventeen, with his hand on her back and his voice in her ear.

He buried her under the pecan tree by the trailer.

Sent me a photo. Just a small mound of dirt, a cross made from scrap wood, and the words:

“She made it, Doc. We both did.”

I keep that picture in my drawer.

Not because it’s grand or dramatic. But because it’s proof.

Proof that sometimes, what saves you isn’t the rescue itself — it’s the promise you made when you were nine years old and barefoot in the heat, carrying a box you refused to let go.

ENDING TRUTH:

The world will try to take things from you.

Sometimes it wins.

But if you’re lucky — or stubborn — you get to keep the ones you carried in with both hands and refused to surrender.