When two hundred alarms sang at once, the church turned to look—and two hundred bikers faced away, marching toward a little girl’s skates and a city’s conscience.

The alarms didn’t wait for permission.

At exactly two o’clock, while camera crews jockeyed for the best angle outside St. Augustine’s and ushers held the doors for black suits and darker sunglasses, a single, clean beep cut the afternoon open. Then another. Then a hundred more—short, insistent notes rising from the old apartments across the street like a flock taking wing.

People looked up from their programs. The preacher paused with his hand on the pulpit. The man from the funeral home who’d told us to leave turned toward the sound the way you turn toward your own name.

We hadn’t touched the church. We hadn’t raised our voices. We hadn’t even crossed the curb.

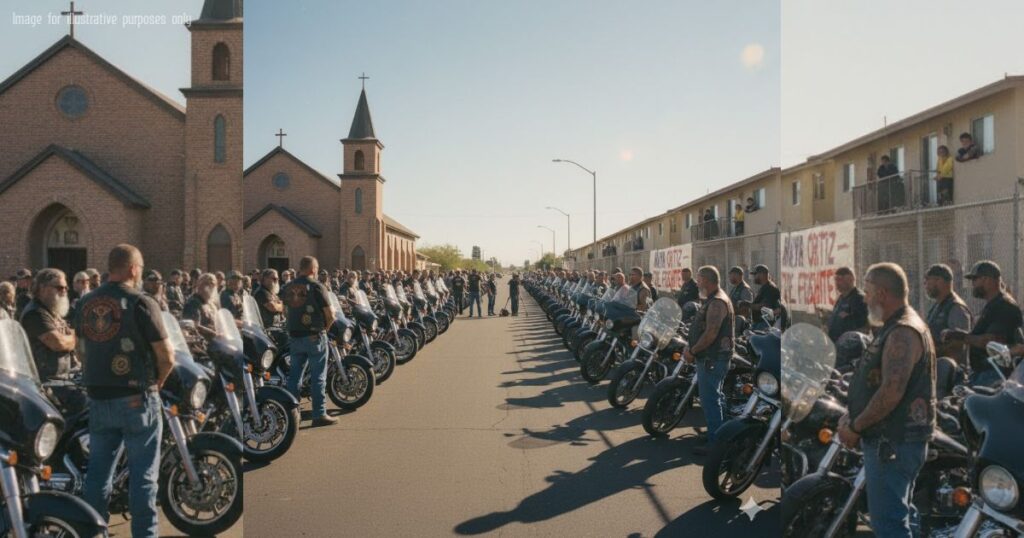

We were already moving—two hundred of us, leather vests and patched denim and faces the Arizona sun had turned into maps. We came in two columns, engines off, boots quiet on the asphalt, the Iron Guardians patch catching the light. I walked in front because I was the one who’d said yes. I’m Hank Delgado, sixty-seven, Desert Shield vet, riding with the Guardians longer than some of the kids filming us have been alive.

“They’re here to crash the funeral,” a woman whispered to her husband, and he shook his head without taking his eyes off us, because what he was seeing didn’t match what he expected.

We didn’t turn toward the church doors. We turned toward the chain-link fence that wraps the block like a warning. Behind it, the Hartley Arms: a three-story maze of thin walls, thick histories, and mailboxes that don’t always lock. The building where, last winter, a ten-year-old named Maya Ortiz pounded on doors when smoke bloomed under the third-floor stairwell, where she shouted and waved her arms until neighbors woke up, where three families made it down the back stairs because a fourth-grader refused to give up. The place where the hallway detector wheezed once, then gave up, and a girl with skinned knees and glittered shoelaces kept shouting anyway.

Maya didn’t get the ceremony heroes usually get. There was no sky blue casket on the six o’clock news, no line of official cars. There was a small service in a borrowed room and a photo printed at the pharmacy and an empty pair of skates on her grandmother’s porch that made people cross the street rather than risk saying the wrong thing.

Across the avenue, Benedict Cross was getting the kind of send-off city pages love—philanthropist, builder, patron of youth sports, first pew full of notables. I’m not a judge and I don’t pretend to be one in leather, but it’s hard not to notice that the building where Maya lived belonged to a company with his name on the paperwork, and that sometimes the money you drop in the offering plate is the same money somebody didn’t spend on a test button.

We didn’t come for him.

We came for her.

The funeral director had stepped into our path when we rolled in earlier, breath tight, palms up; I could hear the word “security” rising in his throat. “Sir,” he said, “this is a private service.”

“Understood,” I told him. “We won’t go near your doors. We’re going to the fence.” I pointed to the Hartley Arms. “We’re here for a memorial across the street.”

“Memorial for who?” he asked, as if the name itself might tell him what to do.

“For the kid who saved a whole staircase,” I said. “And for the ones still sleeping under weak alarms.”

That was all I said then. The rest of it started six weeks earlier, in the digital confession booth where strangers ask for help.

The message came to our club page at 11:18 p.m., sent by a school counselor named Kendra Lee who’d been following our toy runs and our escort rides for Gold Star families.

“I know you don’t know me,” she wrote, “but there’s a grandmother on the West Side who sits on her stoop every evening with a pair of skates in her lap. Her name is Rosa. Her granddaughter’s name was Maya. She’s not asking for anything. She just wants someone to say her kid’s bravery matters.”

I called Kendra back before midnight.

I called Rosa at nine the next morning because dignity lives in daylight.

She answered on the second ring, voice careful and strong the way people sound who’ve had to memorize hard facts.

She told me how Maya was the kind of kid who held the door with her whole body, how she kept emergency numbers on a neon index card taped inside her binder, how she named her skates “Rocket” and “Spark” and promised she’d learn to skate backward by spring.

Rosa didn’t say any ugly words.

She didn’t need to.

We both knew the strings: waiting lists for repairs, forms missing signatures, inspections scheduled for days buildings are closed, calls that take three tries and end with case numbers no one will find again. Everyone is doing their job, and still somehow the batteries go flat.

“I don’t want anybody yelled at,” she said. “I just want Maya remembered for what she did, not for what didn’t work.”

When I brought it to the club, there was a silence I trust.

Not the kind that comes before a fight—the kind that comes before a plan.

We called the fire department first, because you do things right if you want them to last.

Captain Navarro is a big man with careful eyes who’s seen too many kitchens after the fact.

He listened.

He rubbed his chin.

He said, “I can’t tell you what to do, but I can tell you what doesn’t need a permit: loaner ladders, fresh batteries, and test buttons.” He said, “If you keep it peaceful and you coordinate, I’ll have a truck nearby. Not with lights. Just nearby.”

We called the Red Cross and a hardware co-op that lets you sign out tools with your library card.

We called tenants’ groups who know how to show up without turning everything into a brawl. We called a church that knows Rosa’s name.

We called a marching band director who said he could loan us stands for posters if we promised we’d bring them back.

We named it Operation Firefly because one of the older guys, Felix, said that’s what Maya did—she lit the dark long enough for other people to run.

We bought ribbons the color of clear sky and tied them in bows as neat as you’d do for a birthday.

We printed a banner big enough to read from a moving car: MAYA ORTIZ (2014–2024) — LITTLE FIREFIGHTER.

We procured two hundred smoke alarms and twice that many batteries and we practiced with the test button until the sound went from annoying to holy.

We told the press the time and the place and nothing else.

We told them there would be a moment worth staying for.

We did not tell them what building owned which paperwork.

We did not tell them who we thought failed or how. You don’t start with blame if you want people to hear you.

The morning of, I woke up before the sun and did something I’m embarrassed to say I hadn’t done in months.

I dragged a chair under the hallway detector in my condo.

I pressed the button. It answered me in the same stern tone it uses with everyone, like a good teacher who has seen every trick and still believes you can pass if you study.

I stood there and listened to that tone, and I remembered being a poor kid in an apartment the world forgot to paint, remembering the way that battery chirp at three a.m. becomes part of your heartbeat.

I replaced two batteries and felt like I’d confessed a small sin and been forgiven.

By noon we were staging three blocks away, engines ticking, the smell of sun-warmed oil the way some people remember their father’s cologne.

The text came from Navarro: You’re clear. We rolled slow, because dignity doesn’t hurry.