When we turned onto Augustine, the news vans were already feeding a story the producers had written in their heads: motorcycle gang crashes memorial for beloved community leader.

The chyron looked ready to go. You could almost see the headline in the anchor’s eyes.

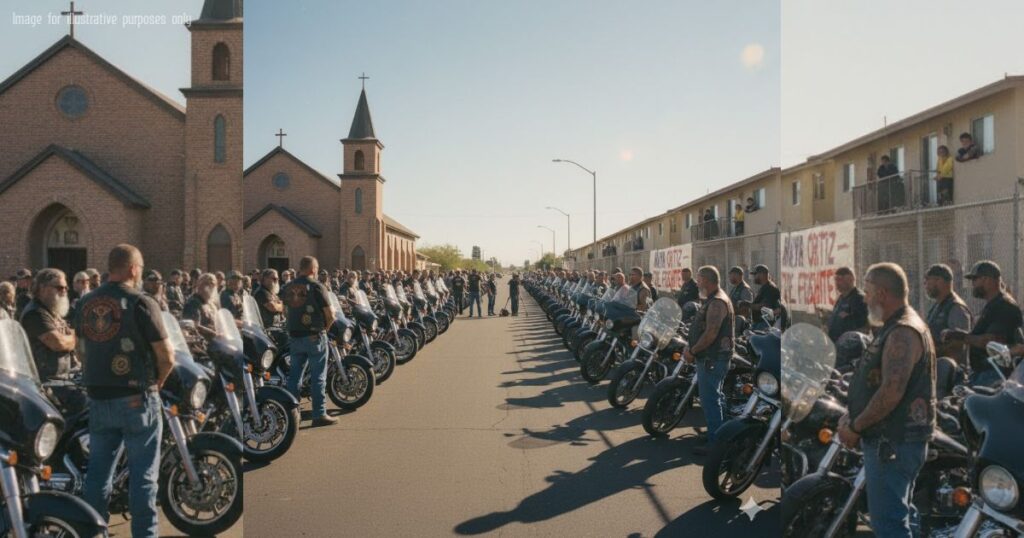

We parked in two lines so clean you could have run a level across the handlebars.

We dismounted. We took off our helmets. We lifted our banner. And then we did the part nobody expected.

We faced away from the church.

The first beep rose exactly on the hour.

A woman in a second-floor window across from the Hartley Arms held up her phone to record and laughed a little through her tears because if you don’t laugh a little when things click, your chest breaks.

A man on the sidewalk took off his baseball cap. The preacher inside St. Augustine’s put both hands flat on the lectern and leaned forward.

The second beep came from the corner unit that used to have magazines piled under the windowsill.

The third came from a ground-floor apartment where a grandmother raises twins.

And then the sound braided itself into something you could feel in the concrete—short, measured, unanimous. Not sirens. Not panic. Not a chorus of fear. A pulse.

I stepped up to the chain-link and hooked the banner in place with zip ties we’d pre-cut because no one looks dignified fighting a stubborn package on TV.

Rosa was waiting for us with a paper bag in her lap. Inside were a pair of roller skates small enough to hold in one hand.

Blue and silver, scuffed, the laces clean. She stood slowly, smoothed her skirt, and set the skates on the lowest rung of the fence where passersby couldn’t miss them.

“Baby,” she said softly, not for us, not for the cameras. “Look what you started.”

We formed a circle because that’s how you keep a center.

Navarro stood off to one side in his plain polo with the station patch, arms folded, eyes full.

Kendra wiped her face with the cuff of her sleeve like a kid at the movies.

Felix took out a folded sheet of paper and read the names of the people who ran because a fourth-grader insisted they should.

He didn’t say how. He didn’t say what floor. He just said names, like taking attendance for a class that made it.

When he finished, I stepped forward because I had promised Rosa I would.

“Folks,” I said, and my voice came out steady because the stakes organize you, “a lot of us come from times and places where the fire code was a rumor and the landlord’s number was a dare.

We learned bad habits, and sometimes we taught them to our kids without meaning to.

Today isn’t about blame.

Today is about remembering a kid who did what alarms are supposed to do—wake people up.”

I turned to the cameras because I wanted this next part on the record.

“If you’re watching this at home, check your hallway. If the battery chirped last month and you pulled it out and promised yourself you’d get a new one when you had time, this is your time. If you don’t have one, call us. Call the Red Cross. Call your neighbor who has a ladder. We’ll come press the button with you. We’ll bring a fresh nine-volt and a smile.”

I nodded and stepped back.

We didn’t chant.

We didn’t point fingers.

We just stayed there while the beeps wound down, the way a song winds down when the drummer lifts his sticks and the room holds a little of the sound just to say thank you.

The church service across the street ended because time is a law even for the important.

The doors opened and the attendees came down the steps in pairs. They didn’t look at us at first. Then they did. They had to, because the banner was big and the skates were blue and the ribbons on the fence moved in the breeze like the quietest kind of flag.

Some of them came closer.

A woman with a pin on her lapel that meant she sat on a board of something pressed her lips together and nodded once at Rosa the way people do when they’ve just learned a truth they can live with.

A man who had given a eulogy ten minutes earlier took off his jacket and draped it over his arm because suddenly it felt too heavy.

The preacher stopped. He read the name on the banner. He closed his eyes for a moment that felt like a choice.

We didn’t say a word to them. Not because we didn’t have words—because the point had already been made by a child and a test button.

That night, the news didn’t run the prewritten segment.

They led with the beeps.

They led with the fence and the skates and a wide shot of two hundred bikers standing the way soldiers stand when the important thing is not them.

They interviewed Rosa on her stoop; she didn’t talk about loss, she talked about courage.

They asked why bikers cared, and she said, “Because they remember what being forgotten feels like.”

In the days that followed, practical things began to grow where the noise had been.

City Hall moved the inspection backlog to the top of the agenda.

A councilmember who’d never once returned an email from a tenants’ group called a Saturday session and stayed until the janitor asked them kindly to wrap it up.

A hardware store on 9th put a sign in the window: SMOKE ALARMS AT COST, BATTERIES ON US. A youth center started a program where kids swap out batteries for seniors and get community service credits and a slice of pizza for their trouble.

Someone launched a website with a big red button that said CHECK YOURS TODAY; by the following week it listed a dozen zip codes with volunteers and ladders.

And because the internet still has a heartbeat, the photo of the skates on the fence went everywhere.

People argued a little, the way people do, about who should have done what when; then the argument shifted to who could do what now. That’s a better fight.

Three months later, on a Saturday so clear the mountains looked close enough to touch, we came back to the fence with a small piece of granite and four bags of river stones.

The city had approved a proper plaque to be installed on a bench later that summer, but Rosa wanted something sooner, something the kids walking by could thump with their fingers and hear the good sound a stone makes.

We set the granite on two bricks and wrote MAYA’S BENCH (TEMPORARY) in chalk and laughed because the word temporary is for bureaucrats and grief; love isn’t temporary and neither is gratitude.

Navarro brought the ladder truck, no lights again, and the firefighters showed the neighborhood kids how the outriggers work and let them sit in the front seat to see the world the way you see it when your job is to arrive.

Kendra held a plastic bin full of nine-volt batteries like Halloween candy and asked every adult who walked past if they were good at promises. “Promise me you’ll put this in,” she said. “Promise me you’ll press the button.”

Rosa dressed the skates in new laces. “Rocket” and “Spark” had lost their charm on the concrete, and the fresh white made them look ready. She set them on the bench and patted their toes.

I pressed the test button on the new detector over the old stairwell.

It answered me.

The sound went out across a courtyard where laundry lines hang like daydreams. It bounced off the brick and came back and landed in my chest the way a drumline lands.

We don’t fix the past.

We don’t get to go back and add batteries to yesterday. But we can make today noisier in all the right ways.