My name is Sarah, I’m 43, and I need to confess something. My daughter, Maya, has fourteen trophies on her bedroom shelf. Every single one is for “Participation.”

For years, I’ve secretly hated those trophies.

I know, I know. That sounds awful. But I come from a different time. I’m from a small town in Pennsylvania where you earned your spot. I played varsity basketball. I knew the sting of losing and the thrill of a game-winning shot. In my world, you got a trophy when you won.

These plastic ribbons just felt like a lie. A participation trophy always felt like it was quietly saying, “You weren’t good enough, but we feel bad for you.”

My husband, Mark, a high school history teacher who sees it all, always told me I was missing the point. “Sarah,” he’d say, “it’s not about the trophy. It’s about her choosing to be in the arena.”

I never understood him. Not really.

Until last Saturday.

My daughter, Maya, is twelve. She’s a wonderful kid—kind, quiet, and artistic. But “athletic” is not a word anyone would use for her. She’s clumsy, still figuring out where her feet are. She’s the kid who says “excuse me” to the referee and “thank you” to the other team’s coach.

She joined the town’s recreational soccer league this fall. Not because she dreamed of being the next Megan Rapinoe, but because her therapist said it was a good idea.

And that’s the part you don’t see from the bleachers.

You don’t see what happened in sixth grade. You don’t know about the “Mean Girl” video. A group of girls filmed Maya trying to do some silly dance from a social media app. They filmed her tripping, edited it in slow-motion, and passed it around the entire middle school.

It broke her.

It wasn’t just bullying; it was public humiliation in the digital age. The shadow that followed was long and dark. We spent the better part of a year with therapists, specialists, and countless sleepless nights. Maya developed severe social anxiety. She ate lunch in the guidance counselor’s office. She quit the art club. She just… vanished into her room.

Her joining this soccer team wasn’t a casual decision. It was an act of war against her own fear.

When she came to me with the sign-up sheet, her hands were shaking. “Mom,” she whispered, “I think… I think I want to try. Becca is on the team, and she said they need more players.”

I held my breath. It wasn’t about soccer. It was about her wanting to re-join the world.

“I’m not good,” she said quickly, her eyes on the floor.

“It doesn’t matter if you’re good, honey,” I told her, my own voice thick. “It only matters that you try.”

So she tried. She practiced in the backyard, kicking the ball against the fence, counting her toe-taps. When she made the team (it’s a rec league, everyone makes the team), she cried happy tears. “They said I belong, Mom. They gave me a jersey.”

Last Saturday was her first home game. The air was crisp, that perfect, sharp New England fall morning. The field was surrounded by parents in puffy vests, clutching Starbucks cups, and yelling just a little too loud.

Maya played for about ten minutes in the second half.

She was… well, she was Maya. She ran when everyone else walked. She stopped when everyone else ran. She missed a kick completely and spun herself onto the grass. She got up, bright red, and looked for her position.

But she was smiling.

And I was smiling, too. That old, competitive part of me was just… gone. I wasn’t watching a bad soccer player. I was watching my daughter win the biggest fight of her life. I was watching her be on a field she was terrified of. My heart felt so full, I thought it might burst.

And then I heard it.

It came from the row of dads behind me. The “pro-dads,” the ones who pace the sidelines and wear gear from the teams their kids wish they were on.

“Good God, Coach,” one man muttered, loud enough for half the bleachers to hear. “Put number 12 on the bench. She’s dead weight.”

A woman next to him laughed. A short, sharp, barking laugh. “That’s the ‘everyone gets a trophy’ problem right there. Just pathetic.”

Another man chimed in. “My son has to work twice as hard to make up for her. This isn’t charity.”

They didn’t whisper. They didn’t look around to see who was listening.

They were talking about my daughter.

My baby.

The blood drained from my face. My Starbucks cup crumpled in my hand. I wanted to stand up. I wanted to turn around and unleash a firestorm.

I wanted to scream, “Her name is Maya! Do you know what it took for her to even put on that jersey? Do you know about the video? Do you know she spent last year convinced she was worthless? That she is the bravest person on this field today? That your ‘star’ son is probably one of the kids who laughed at her?”

I wanted to tell them that this game, in this town, in this divided country where we’ve forgotten how to be neighbors, isn’t about a scholarship. It’s not the World Cup. It’s about a twelve-year-old girl trying to find her footing in a world that has been relentlessly cruel.

But I didn’t.

I just sat there, my insides shaking, and gripped the cold, metal bleacher until my knuckles turned white.

The whistle blew. The game ended. They lost, 4-1.

Maya came running over to me, her face flushed with sweat and pure joy. She was beaming.

“Mom! Did you see it? Did you see that part where I almost kicked it? Coach said my positioning was way better! He said I’m improving!”

And I smiled. The biggest, most painful, proudest smile of my life. I hugged her sweaty head to my chest. “You were amazing, honey. I saw it all. I am so, so proud of you.”

She didn’t hear them. Thank God.

But I did. And I will never, ever forget.

Driving home, Maya hummed along to the radio, talking about the orange slices. And I thought about those men. I thought about the parents who measure their child’s worth in goals and their own worth in their child’s success.

We’ve become a culture of critics. We sit safely in the stands—or behind our keyboards—and we tear down the people who are actually in the arena, trying. Especially the ones who are clumsy. Especially the ones who are vulnerable.

We complain about the “next generation,” but we are the ones teaching them. We are teaching them that kindness is secondary to winning. That compassion is for the weak. That “dead weight” is an acceptable thing to call another human being.

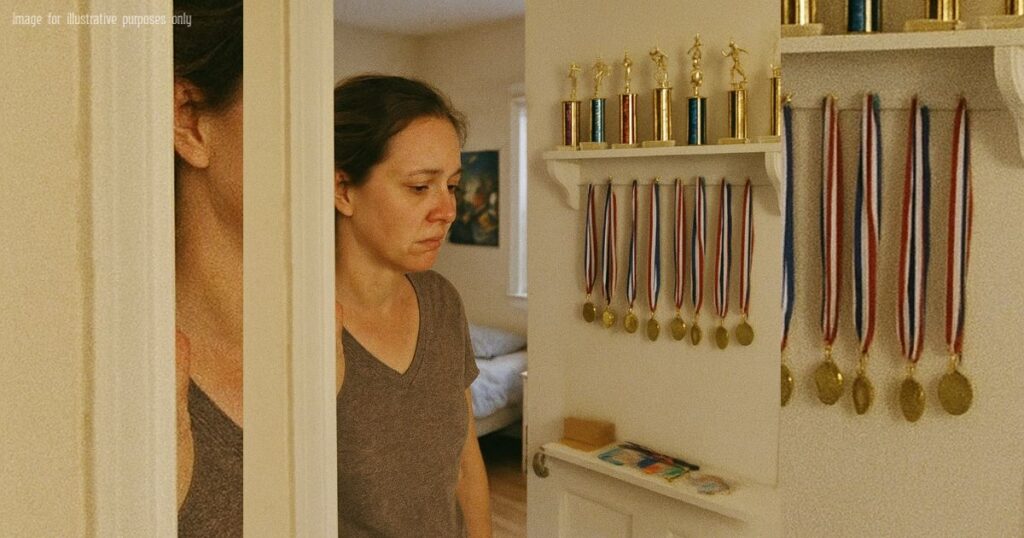

When we got home, I walked into Maya’s room. I looked at those fourteen “participation” trophies.

And for the first time, I finally understood.

They aren’t “trophies for losing.”

They are “trophies for showing up.”

They are monuments to courage. They are a receipt for all the practices, all the fear, all the anxiety, and all the mornings she wanted to stay in bed but got up anyway.

That trophy isn’t a lie. It’s the most honest thing in the room.

So here is my message. To the dad in the bleachers, to the mom who laughed, to every adult who thinks a kid’s game is their personal Super Bowl:

Every child out there is someone’s whole world. You don’t know the battles they are fighting just to be on that field.

And your words—even the ones you mutter to your friend—matter. They are a wrecking ball. You are teaching your own “star” child that it’s okay to mock the kid who is struggling. You are building the bully you claim to hate.

These games aren’t about winning. They are about becoming.

Cheer loud. Encourage often. Stay humble.

And when you feel tempted to judge a child who’s still learning, remember this: They are already doing something you’re not.

They’re trying. In public. While you sit safely in the crowd.

My name is Sarah. And my daughter is a champion. You just can’t see her trophy from where you’re sitting.

Click the button below to read the next part of the story.⏬⏬