I packed my bags the moment my eleven-year-old grandson looked at a single drop of his own blood and asked, in absolute terror, “Am I going to die?”

My name is Joe. For forty-five years, I was a general contractor. My hands are rough like sandpaper, scarred by sheet metal and honest work. But for the last year, I’ve been a “guest” in my son Mark’s pristine, solar-powered smart home in the suburbs—a place where the fridge tweets you when you’re out of milk, and the children are allergic to the outdoors.

I moved in after my wife, Martha, passed. I sold my paid-off ranch house to help Mark with his massive mortgage. I thought I was joining a family. I didn’t realize I was moving into a sterile fortress where “safety” is a religion.

Mark and his wife, Cheryl, are good people. They are “Data Analysts” who work from home, staring at dual monitors for ten hours a day. But they are terrified. They are terrified of bacteria, of conflicting opinions, of unsupervised play, and of failure.

Their son, Noah, is eleven. He is a sweet kid, but he is ghostly pale. He has anxiety about things he sees on TikTok. He spends his life in a gaming chair, building digital empires in the metaverse, yet he doesn’t know how to tighten a loose screw on his own bedframe.

Last Tuesday, I decided I couldn’t watch it anymore.

I found Noah in the living room, eyes glazed over, headset on.

“Noah,” I said, peeling the headset off. “Boots on. We’re going to the garage.”

“Why?” he whined, shielding his eyes from the window light. “I’m in a lobby waiting for a match.”

“Because you’re almost a teenager and you think plumbing is magic. We’re building a planter box for your mother.”

Cheryl looked up from her standing desk in the kitchen. “Joe, wait. The air quality index is moderate today. And tools are… aggressive. Noah has his coding boot camp in an hour. We don’t want to overstimulate him.”

“He’s not overstimulated, Cheryl,” I said, trying to keep my voice even. “He’s under-challenged. He thinks Amazon delivers competence in a cardboard box.”

I dragged the boy to the garage. It was filled with boxes of my old tools—my life’s work—pushed into the corner to make room for their Peloton.

“This,” I said, handing him a sanding block, “is how you smooth out the rough edges. In wood, and in life.”

For two days, it was a struggle. Noah complained about the sawdust. He complained his wrist hurt. But on the second afternoon, he drove a screw flush into the cedar plank. I saw a spark in his eyes. A tiny flicker of real pride that no “Like” button could ever give him.

“It’s solid,” Noah said, surprising himself.

“It is,” I nodded. “Now, let’s trim the edge.”

Then, the accident happened.

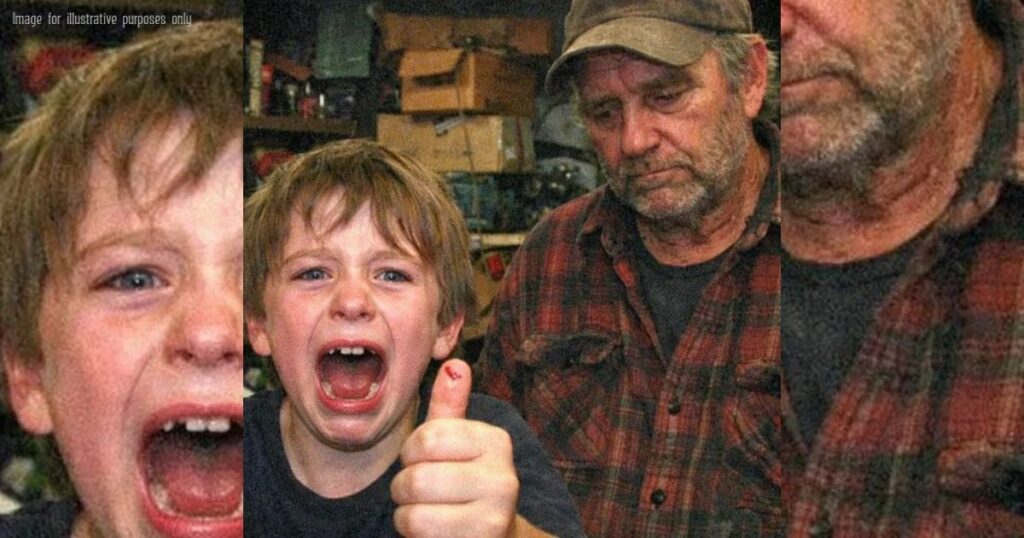

It was nothing. The chisel slipped. It grazed the side of his thumb. A tiny bead of crimson appeared.

Noah froze. He stared at his thumb like he’d been shot by a sniper. Then, the screaming started. It wasn’t pain; it was panic.

“Grandpa! I’m leaking! Oh god, I’m leaking!”

“Breathe, son,” I said, reaching for a shop rag. “It’s a scratch. Put pressure on it. You’ll live.”

The door burst open. Mark and Cheryl rushed in like a SWAT team.

“What happened?!” Cheryl shrieked. She grabbed Noah’s hand, inspecting the 2-millimeter cut. “Mark, get the keys! We need to go to Urgent Care. It might need a butterfly closure! What about tetanus?”

“It’s a paper cut, for crying out loud!” I barked. “Put a band-aid on it and let him finish the job!”

Mark turned on me, his face purple. “Dad! Stop! This is exactly why we hesitate to leave him with you. You’re reckless! You push him too hard. He’s a sensitive child, not a construction worker!”

“He’s a boy, Mark! When you were his age, you were helping me re-shingle the roof!”

“And I hated it!” Mark yelled, his voice cracking. “I hated the heat, I hated the work! That’s why I studied so hard—so my son would never have to use his hands for anything other than a keyboard!”

They ushered Noah inside like a wounded soldier. “It’s okay, sweetie. Mommy will get the iPad. We’ll order DoorDash. You don’t have to go back in there.”

Noah looked back at me. I waited for him to show some grit. instead, he looked at me with betrayal. “You let me get hurt,” he whispered.

I stood alone in the garage, surrounded by silence and sawdust.

That night, I heard them talking in the kitchen.

“It’s too much stress, Mark,” Cheryl said, her voice low and clinical. “Joe’s ‘tough love’ is toxic. It’s archaic. Noah is traumatized. We need a boundary.”

“I know,” Mark sighed. The sound of a defeated man. “I’ll look into that Assisted Living facility in Arizona. The one with the golf carts and the 24-hour nurses. He’ll be safer there.”

Safer.

That word broke me. Not “happier.” Not “valued.” Safer. As if I were a loose railing or a trip hazard.

I didn’t sleep. I spent the night packing.

I didn’t pack golf shirts. I packed my tools. The drills, the levels, the heavy iron clamps. I loaded them into my 2005 pickup truck—the only thing in that driveway without a backup camera.

At 5:30 AM, Mark came out with his artisanal coffee. He saw the loaded truck.

“Dad? What are you doing?”

“I’m leaving, Mark.”

“Where? You can’t just drive off. You’re seventy-two.”

“I’m going where I’m useful.”

“Dad, stop. We can discuss this. Just… no more tools. Just be a grandpa. Watch Netflix. Relax. We’ll take care of you.”

I looked at my son. He looked soft. He was a good man trapped in a golden cage, terrified that the wind might blow too hard on his child.

“Mark,” I said. “You think you’re protecting that boy. But you’re crippling him. You’re wrapping him in bubble wrap and waiting for the world to crush him. The world doesn’t care about his anxiety. Someday, something is going to break—a pipe, a car, a bank account—and he won’t know how to fix it because you never let him hold the hammer.”

“You’re being dramatic,” Mark scoffed. “We can hire people to fix things.”

“You can hire people to fix leaks,” I said, climbing into the truck. “You can’t hire someone to fix character.”

I drove three hours south, to the inner city. To a neighborhood where the porches sag and the hope is hard to find. I pulled up to “Second Chance Trade School,” a struggling non-profit program for at-risk teens.

I walked into the director’s office.

“I’m Joe,” I said. “I have forty-five years of master carpentry experience and a truck full of tools. I want to donate them.”

The director looked shocked. “Sir, that’s… thousands of dollars. Do you want a tax write-off?”

“No,” I said. “I want a job. Volunteer. I want to teach these kids how to build real things. Not digital castles.”

He hesitated. “Sir, these kids… they’ve had hard lives. They don’t listen well.”

“Good,” I smiled. “That means they’ve got grit.”

That was six months ago.

My shop class is full every afternoon. These kids don’t have noise-canceling headphones. Most don’t have dads at home. When they hit their thumb with a hammer, they don’t call a lawyer. They shake it off, wrap it in duct tape, and keep swinging. They are hungry for competence. They want to know they can change their reality with their own hands.

Yesterday, a massive winter freeze hit the state. The power grid failed.

I was at the shop, showing a sixteen-year-old named Marcus how to frame a load-bearing wall. My phone buzzed.

It was Mark.

Dad. Power is out. Smart thermostat is dead. The house is freezing. A pipe burst in the basement and water is everywhere. We don’t know where the main shut-off valve is. Noah is panic-attacking. Can you come over? We need you.

I looked at the text. Then I looked at Marcus. He was holding the level, focused, proud. He had just cut a perfect angle.

“Mr. Joe?” Marcus asked. “Is this straight?”

I put the phone back in my pocket.

“It’s perfect, son,” I said. “Now, let’s nail it down.”

I didn’t reply to Mark. I love him, but I’m done being the safety net for people who refuse to learn how to fall.

We have confused “comfort” with “love.” We have raised a generation that is technically brilliant but functionally helpless. We threw away the toolbox because we thought an app would save us.

But the storm always comes. And when the Wi-Fi dies, the only thing that will save you is what you can do with your own two hands.

I’m not a retired relic. I’m a builder. And for the first time in years, I’m building something that will last.

—

A week after I ignored my son’s desperate text, the internet decided I was the worst grandfather in America.

At least, that’s what the comment section said.

I didn’t even know about the post at first. I was too busy showing Marcus and three other kids how to braze a copper joint over a propane torch without burning the place down. The city pipes were still half-frozen. Our shop smelled like metal, damp plywood, and cheap hot chocolate. Real life.

It was one of the other volunteers—a younger woman named Tasha—who showed me her phone during a break.

“Mr. Joe,” she said carefully. “Is this… you?”

On the screen was a long paragraph posted to a parenting group. No names, no last names, but I knew it was us before I even finished the first sentence.

“My elderly father chose ‘at-risk teens’ over his own grandson during a dangerous winter storm. Our smart systems failed, the house was flooding, and he ignored our message. My son had a panic attack. Is this emotional abuse? How do we protect our child from a grandparent like this?”

Click the button below to read the next part of the story.⏬⏬