Seventy miles into a heatwave that bent the highway like a mirage, a biker in a patchwork vest hovered in my mirrors so steadily I started counting exits like prayers. I changed lanes; he changed lanes. I kept my hands at ten and two and tried to breathe like a calm person would.

I am seventy-eight and a widow, and I have been driving since cars still smelled like steel and vinyl and hope. I do not scare easily. That day, fear rode shotgun and kept flicking the lock with a cold finger.

The dashboard air felt like a hair dryer even with the fan whining on high. Electronic signs flashed Red Flag Warning ahead, and the radio mumbled about rolling outages and crews spread thin. Somewhere underneath the dryness and wind, a faint thrumming came and went like a moth behind a lampshade.

He stayed two car lengths back and matched me beat for beat. When I eased off the gas, he did too. When I nudged into the right lane for the next rest stop, he drifted over as if tethered to my bumper by invisible wire.

The rest stop shimmered in the heat, low trees bent away from the wind, two vending machines ticking like crickets. I pulled into the first patch of shade and locked the doors. The biker rolled to a stop three spaces away and killed the engine.

He took off his helmet and became a person, not a shape. Gray at the temples, brown skin sun-cooked to a soft leather, eyes that did not flinch. He lifted both hands, palms out, and pointed—not at me—but down, toward my rear wheel.

I dialed 911 because my daughter would have wanted me to, and the dispatcher answered on the second ring. I told her where I was, what I saw in my mirror, and how my voice shook even though I hated that about myself.

“Stay in your vehicle,” she said, steady as a metronome. “Help is on the way. If he approaches, crack the window only an inch.”

He did not approach. He waited for me to see that he was waiting. Then he pulled a phone from his pocket and held it up so I could see the screen through my windshield.

On the screen, a short video looped: my car from the biker’s point of view, the rear wheel quivering, the rim shimmering wrong. He tapped to replay it and pointed to his ear, then to me, like a pantomime: hear that, please.

The dispatcher asked if there was smoke, flames, any immediate danger. “Just heat,” I said, and my voice had already dropped a half step because the video took a bite out of my fear. “And maybe foolishness.”

The biker took a cautious step closer and spoke through the glass.

His voice was low and even, like the hum of a window fan. “Ma’am, your rear wheel is walking. Please don’t drive another yard.”

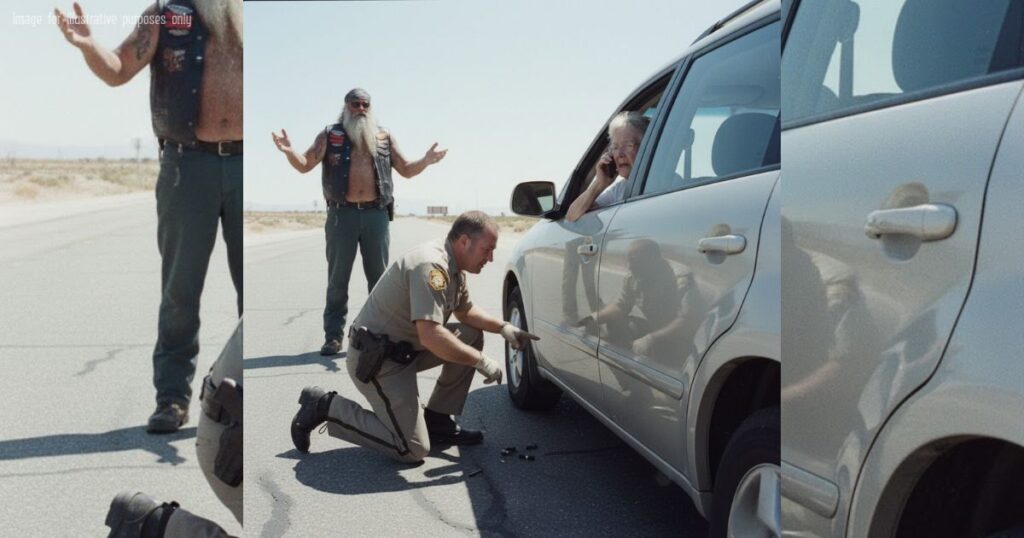

The sheriff’s deputy pulled in with lights but no siren, dust swirling around the grille.

He parked in a slice of shade and moved like the day belonged to him, but kindly. “Good afternoon,” he said through my window. “Let’s take a look together.”

We walked to the back of the car, the biker trailing at a respectful distance.

The deputy crouched and touched the metal, then snatched his hand back. “Hotter than it has a right to be,” he said. “Ma’am, you’re missing a lug nut, and two are barely holding. If you’d hit a bump, that wheel could’ve come off.”

The world went silent except for the tired tick of my engine.

I thought of the weight of my years and of the trumpet case on the back seat, the one that belonged to my boy when he was still here, the one I had polished for my granddaughter’s audition.

The biker shifted his weight and kept his eyes on the pavement.

“I ran alongside and pointed,” he said softly. “I tried to get ahead and wave you down. I didn’t want to spook you more.”

“I was already spooked,” I said, and the deputy’s mouth smiled a little the way you do when all the dots finally connect into a picture.

“Tow is on the way,” the deputy said. “Please don’t drive. In this heat, metal expands, and things fail fast. We’ll get you sorted.”

A gust of wind pulled a thread of smoke across the sky like a gray ribbon.

The deputy’s radio crackled: brush fire miles west, wind change, crews stretched.

He looked toward the hills, then back to us. “We may have to stage at the community center if the wind shifts,” he said. “Let’s stay ready.”

The biker nodded once like action was a language he spoke fluently.

He touched the small pouch on his belt—habit, I could tell—and then turned to me. “Name’s Cal,” he said. “Cal Morales. Folks call me Stitch.”

“Nora,” I said, because I am not made of suspicion alone. “Thank you for stopping.”

Another breath of smoke salted the air.

The deputy’s radio murmured again, hotter now, and he took a long look at the scorched grasses near the highway.

“Tow truck is rerouting,” he said. “We’re moving to the community center two miles east. Ms. Nora, you’ll ride with me. Mr. Morales, if you don’t mind trailing behind to keep folks off her bumper.”

“That’s exactly what I had in mind,” Cal said, and the way he said it unknotted something small at the base of my throat.

We crept at school-zone speed, the deputy in front, me in the middle, Cal a steady shadow behind.

The left rear made a sound like a spoon clinking a glass every time the road seam hit just right. I held the trumpet case against the seat with my free hand as if music could hold a wheel on.

At the community center, the air conditioners fought and lost but still tried.

Volunteers passed out water bottles and damp cloths. People sat with their forearms on folding tables, cheeks pinked by heat, speech slowed to something kinder.

I took three small sips like my doctor had taught me and still the room tilted.

Cal appeared with a packet of electrolyte powder and asked before he opened it, which is a detail I will remember longer than the taste itself.

He watched my hands, not my face.

“Pulse is too quick,” he said to himself, not as a diagnosis but as a reminder to keep time. He had the voice of someone who had talked people through hard minutes in small rooms.

I asked him how he knew. He told me he had been an EMT once, then a volunteer when someone at his plant collapsed, then the kind of neighbor who keeps a glove box pharmacy with permission and training and a laminated card.

Around us, two men argued without raising their voices about who should have cut which budget when and why.

Cal stood and touched the table lightly with both hands. “Hey,” he said. “We’re in the same room with the same air. Today that’s what matters.”

They nodded because it was too hot for pride, and we all drank more water.

The deputy rolled two giant fans to the corner where the oldest folks sat. I watched him crouch and smile and make a child laugh by pretending the fan was a rocket ship and he was the countdown.

Cal asked if the trumpet was heavy.

I said heavy in all the ways a thing can be. He asked who had played it first, and I told him about my boy and the marching band and the years that turned without his sound in them.

I told Cal I had promised my granddaughter she could have the trumpet if she kept practicing even when it was not fun, because music is both a key and a stubborn lock and you cannot learn the turn without sore lips and patience. Cal said he did not know music but he knew stubborn, and we both smiled like old co-conspirators.

The tow truck found us at last, heat shivering above its hood.

The mechanic did not sugarcoat it.

A stud was stripped. One lug nut had vanished like a coin in a trick gone wrong. He had spares and the right tools, though, and a face that said this was not the worst problem in the world on a day with bigger ones.

Cal unrolled a pouch of wrenches with a care that looked like prayer. “Mind if I check the torque when you’re done?” he asked, and the mechanic said he would be grateful for another pair of eyes.

They worked together with easy respect, the deputy spotting like a third hand.

When the last nut was seated and the wheel faced the world squarely again, Cal leaned on the wrench until it clicked and then did it again in a star pattern the way you teach new drivers who still believe bolts are magic.

The deputy put a sticker on my windshield that said inspected, the adhesive sighing as it met glass. “You can drive now,” he said. “But I’d take it slow and steady, and I’d let your friend here follow for peace of mind.”

I turned to Cal and all the fear that had sloshed around in me like hot water found a drain. “I was wrong about you,” I said. “I saw patches and assumed trouble.”

Click the button below to read the next part of the story.⏬⏬