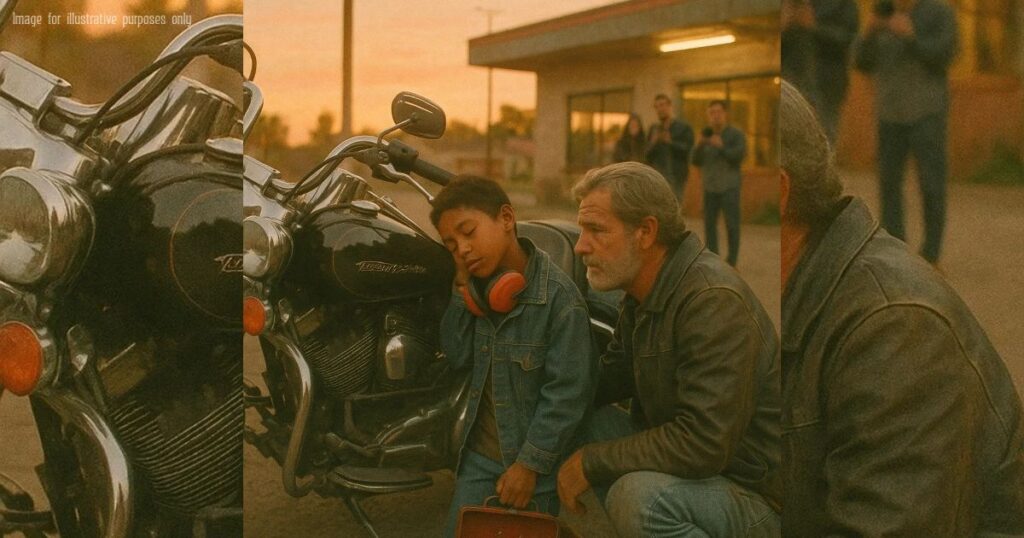

The boy pressed his ear to my idling Harley like it was a heartbeat—barefoot on hot Ohio asphalt, eyes closed, counting breaths—and the whole parking lot forgot how to breathe.

People had their phones out. The late sun threw long orange lines across the concrete, pulsing off chrome and glass like a slow lighthouse. A sedan had just swung wide around the pumps at my little two-bay garage and rolled off with the radio still thumping, left a swirl of dust, and didn’t come back. The kid stayed. Skinny, eleven maybe. A denim jacket two sizes too big, a lunchbox dangling from one hand, a small tin rattling inside like rain. He didn’t cry. He just laid his cheek against the tank of my Road King and breathed in the fumes like it was fresh bread out of an oven.

“Hey, buddy,” I said, soft as I could make it. “That metal is warm.”

My name’s Ray Delgado—folks at the union hall used to call me Steel—and I’ve been listening to engines my whole life. Ironworker for thirty years. Knuckles like old bolts. Widower. I run a neighborhood garage that still writes estimates on a clipboard. I’ve seen all kinds of hard days sputter in on a flatbed. But I’d never seen quiet like that kid’s quiet.

He flinched when a pickup gunned it onto the road. Not a big flinch—just a tremor through the shoulder, a shutter of the jaw—like the sound skipped across a lake inside him. He pressed harder into the tank. The engine was in a sweet idle, eight hundred RPM, even as a metronome. My fingers went to the throttle on instinct, ready to back it down if I had to.

A man in a polo held his phone lower. “Sir, is he with you?”

“He is now,” I said.

I keep a pair of kids’ ear defenders in the cabinet by the register. The club buys them in bulk every August with the backpacks we donate to the elementary school. I slipped the muffs over the boy’s head, slow as you’d offer a bird your open palm. He let me. He didn’t look up. He touched the engine guard with two fingers, then the tank again, as if mapping a safe route in a city he didn’t know.

“Name’s Ray,” I said. “This bike’s called Heartbeat. Sounds like you already figured that out.”

The phone man cleared his throat. “The car that dropped him—”

“Plate?” I asked.

He shook his head, guilty, and tucked his phone away.

A woman with a floral tote approached, voice high with worry. “Shouldn’t someone call the—”

Blue lights slid along the far curb before she finished. A city cruiser rolled in with the calm of people who see the world at its edges. A second car followed. The officers were kind. They always are with me; I change their oil at cost and keep coffee hot for whoever’s on nights. One of them radioed that Child Protective Services was en route. The other crouched to my height and asked something with his eyebrows. I lifted my hand, not to stop him, just to say quiet, please. He nodded.

“Buddy,” I said again to the boy. “This the only sound that doesn’t hurt?”

He whispered. It was so faint I felt it more than heard it. “Yes.”

I didn’t know then that he’d said more in that one syllable than he’d said in months. I just knew the ground under us steadied.

He still had the lunchbox. It was metal, dented, red. I eased my hand toward it, and he pulled it close, then seemed to reconsider and tipped it open himself. Inside was a smaller tin, the kind that used to hold mints, now filled with bolts. Washers. A few nuts of different sizes. Each piece was labeled in tiny careful handwriting with a date. He pinched one between his fingers, set it on my floorboard, and tapped once. The message was there if you knew how to hear it: order from noise. One small steady thing.

The CPS caseworker stepped out of a county sedan fifteen minutes later with a folder tucked to her ribs.

I recognized her.

Ms. Greene.

She’d been in here last winter during a cold snap, and I’d loaned her a heater for her trunk so she could keep spare blankets warm. You learn things, running a little shop. Like who has to carry warm blankets around on purpose.

“Ray,” she said, and then she saw the boy. “Hi there. I’m—”

He tightened his hands on the tin. The ear defenders muffled the edges of her voice, but it still wobbled the air. He stepped closer to the Harley like it was a doorway that would lock if he got inside fast enough.

Ms. Greene didn’t push. “We got a call,” she said to me. “Anyone know his name?”

“You can ask,” I said, “but maybe do it like you’re watching a deer.”

She smiled with one side of her mouth. “Hi, honey,” she said to him. “My name is Ms. Greene. What’s yours?”

He stared at the reflection of the sky in the tank. The clouds were making a slow parade.

“It’s okay,” I said. “You can tell her later.” I looked at Ms. Greene. “Let me keep him here for a bit.”

“You know the drill.”

“I do. Dee’s on her way.” Dee is with our club and with CASA—Court Appointed Special Advocates—when the jacket comes off. She drives a bright yellow scooter that buzzes like a tired bee. She knows the family court calendar better than some judges.

“Emergency placement?” Ms. Greene said, hopeful and tired all at once.

“If he wants it,” I said, and looked down. “You want to wait with me, buddy? Just for tonight?”

He nodded. Not a maybe. A whole-body yes that started with his heels and moved up like a slow wave.

“Okay,” Ms. Greene said. “Okay.”

His name was Noah.

I learned it when he finally showed me his lunchbox lid from the inside, where someone had pressed vinyl letters crookedly across the paint.

NOAH.

There was also a school picture tucked behind the tin: a boy who looked like a younger version of the boy in front of me, chin up but eyes somewhere else. He carried his tin everywhere, like a passport.

I made mac and cheese because it’s what I know to make gentle.

I put it in the blue bowl because the blue bowl doesn’t clink the spoon. He stood while he ate, at the corner of the counter nearest the garage door. Some kids sit cross-legged; some stand like a runner half in motion. I didn’t tell him to sit. I don’t tell the wind how to move around my shop either.

“You can use words,” I said, the way my wife used to say it to me when grief made my mouth go quiet. “Or you can point. Either way, I’ll follow.”

He touched his ear defenders, then the little tin, then the bike through the open door. He tapped the tin once, twice, then stopped like he was listening to something inside his body. “Steady,” he said.

“Steady is good,” I said. “Steady is the best flavor we’ve got.”

I set up a corner in the living room with things that don’t shout: a weighted blanket, a lamp with a warm bulb that won’t flicker, a shelf where the tin could sit like a trophy.

I pulled my old tool cart inside, wiped the grease off the drawers, and labeled them with a black marker: 1/4″, 3/8″, 1/2″. He ran his fingers over the letters, not reading out loud but reading.

He took the marker, turned the lunchbox over, and wrote on the bottom. A small square. A circle around it. He looked at me like he’d set a flare.

“What does that mean?” I asked.

He tapped the bike. Then the square he’d drawn. Then my chest, right over my heart. “Home,” he said, and the word sounded like it had walked a long way to get here.

We didn’t talk about who had left him or why. I have learned you don’t interrogate a storm. You build a dry place and make soup until it passes.

Dee came by with forms that first night, a little winded from the hill, hair sticking out from under a knit cap.

She’s one of those people who can step into a room and lower the temperature by three degrees, not cold, just calm. She showed Noah her badge. She showed him her scooter helmet with stickers on the back. She asked if she could set it near his tin. He nodded.

Ms. Greene returned with a bag of essentials, the kind of bag that looks like it was packed in a hurry because it was. She had a clipboard and a worry crease between her eyes. “You know we’re over capacity everywhere,” she said quietly to me on the porch. “We’ve got good foster folks. They’re just… tired.”

“We all are,” I said. “Let him catch his breath here.”

“You’ll need a home walk-through. Background check. The judge will want a plan.”

“I’ll give him my plan,” I said. “Steady.”

She looked down at the scuffed porch boards, at the little line of bolts organized by size on my rail, at the Harley glinting like a friendly animal in the yard. “Steady,” she said back, and something in her shoulders softened.