The Second Chance Riders showed up the next morning because that’s what we do when one of us says, Hey, I’ve got a project.

It’s in our bones: you call, we bring coffee and a tool belt. We’re a funny crew if you only look with one eye. Leather. Road patches. Old steel-toe habits we never lost.

Some of us fought wars. Some of us fought graveyard shifts. All of us carry a story or two in our pockets next to the socket wrench.

We replaced the loose porch step and added a handrail because kids like something to hold when they’re making up their minds. We put felt pads on chair legs.

We swapped the light in the hallway for one that warms to full glow instead of popping on.

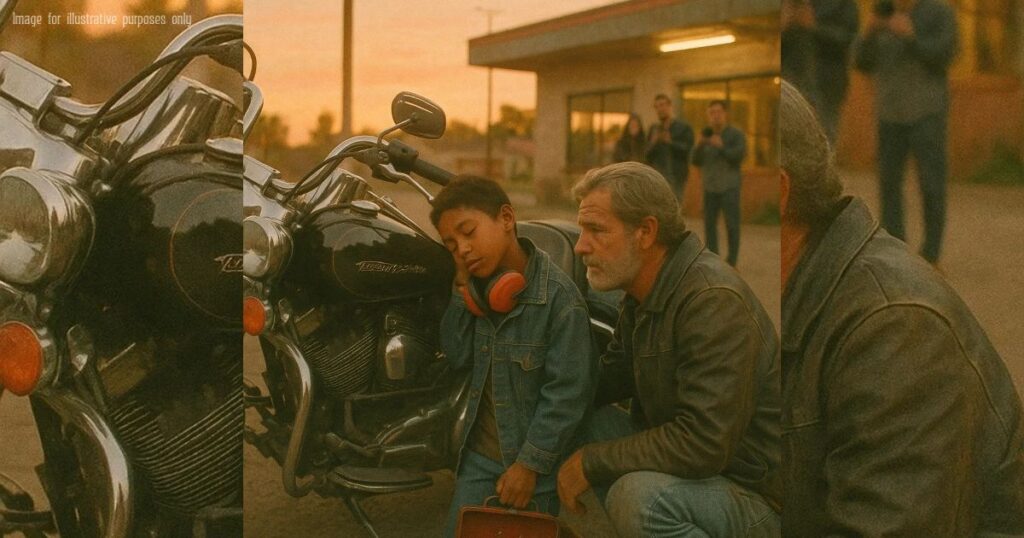

Bear—who is gentle precisely the way you’d think someone named Bear might be—showed Noah how to take apart a carburetor on a little Briggs & Stratton we use for demos. Noah didn’t speak, but he leaned so close his eyelashes touched the metal.

Snake rolled out a mat by the bike and, sitting cross-legged, taught Noah how to count breaths in sync with idle.

“In on the first four, out on the next four,” he said, his voice thick like a bass guitar. “If the world tries to rev, you keep your lungs on idle. You get to decide.”

Noah touched his tin. Picked out a bolt the color of old nickels and set it on the mat between them like an offering. Snake nodded solemnly, as if he’d just been given something sacred. He had.

By noon, my fence was fixed, and the doorbell was disconnected with a little handwritten sign: KNOCK SOFT.

People came and went with the care of folks in a library.

I kept the bay doors wide because Noah liked the line of sight from pantry to tool chest to Harley to sky.

Every once in a while he would stand at the threshold and simply breathe, shoulder-bones rising like small hills, the lunchbox tin held to his chest, listening to a sound only he could hear.

That afternoon, a man came up the walk with a hat in his hands, and I knew who he was before he got within twenty feet. You can tell a lot from the way someone carries a hat.

He wasn’t a stranger—no one in our corner of town really is—but we’d never spoken more than hello.

Marcus Carter. He worked two streets over at a warehouse when he could get the hours. He stopped at my bottom step like he’d run into a glass wall.

“I heard,” he said, and then stopped and started again. “I heard my boy was here.”

He looked past me, over my shoulder, eager and careful at the same time. I didn’t block his view. I also didn’t move aside. There’s a balance to these moments. Give ground too fast, you send the wrong signal. Hold too hard, you turn a doorway into a door.

“Ms. Greene called you?” I asked.

He nodded. He didn’t step closer.

He held the hat like it was made of wet paper. He looked tired in the way that sinks into joints. “I’m working on myself,” he said. “I’m not there yet. But I’m working.”

I believed him. Not because of the words, but because he kept looking for something to do with his hands and chose to do nothing. That’s hard work.

“You can sit,” I said, pointing to the porch chair I’d just sanded down. “You can see him from there. If he wants to see you up close, he’ll come closer.”

He sat.

He didn’t call out.

He didn’t cry.

He didn’t run stories about last time or next time. He just watched his son stand in a triangle of sunlight and hum at an engine like it was a hymn.

Noah noticed him eventually.

You could see the awareness move across his skin.

He tilted his head, and the ear defenders shifted. His eyes, which were a steady brown like a walnut shell, slid to the porch. He stood there for a long time, then took two steps forward, then one back, then put the tin on the floor and opened it.

He took out three bolts and rolled them across his palm before setting them down on the top stair, in a neat, careful row. He tapped each—one, two, three—and then he tapped his own chest, then the Harley’s tank, then the bolts again. Not a sentence. A map.

Marcus put his hat on his knee and set his hands on the boards so the boards wouldn’t float away. “Hey, little man,” he said, and the words were steady. “I see you.”

That was all.

Ms. Greene came by an hour later because that’s what she does when a day might turn into a night that changes a life.

She sat with Marcus and me and talked through possibilities without making promises no one could keep.

Trial visits when he hit certain marks on paper.

Support groups.

Dee added a piece or two about CASA advocates and parent coaching. We built a plan right there on my porch, not fancy, not fragile, just a plan built like a good shelf: level, with more studs than you think you need.

That night, Noah took the smallest bolt out of his tin and set it by my coffee mug.

He pointed to the Harley. He pointed to his heart. He held his hands up like a scale. “Idle,” he said, turning the word over in his mouth as if he were checking for sharp edges.

“Idle,” I repeated. “We don’t have to rev to get home.”

He let me tuck the weighted blanket around his shoulders on the couch.

I slept in the recliner across the room because sleep is easier when you can hear another person breathing.

Somewhere around two, thunder rolled far off, and he jerked awake, eyes wide. I didn’t say, It’s okay. I said, “We can count together.” We counted to four in and to four out, and somewhere between one breath and the next, his eyelids eased.

The walk-through happened on a Tuesday afternoon that smelled like cut grass.

Ms. Greene clicked her pen, and Noah watched the pen with a tiny smile because it made a satisfying sound when the spring did what springs do. She checked the smoke detectors and made a note when I showed her the fire extinguisher by the back door.

The club arrived early to rake leaves that didn’t need raking and to install a deadbolt that didn’t really need installing. Sometimes dignity is a job to do with your hands.

She asked Noah if he felt safe here, and he didn’t answer with words.

He opened his tin, set five bolts on the table, and arranged them into a little picture that looked like a house with a porch and a circle out front. He tapped the circle. “Steady,” he said.

Ms. Greene laughed softly. “That’ll preach,” she said to no one in particular, and checked a box.

The hearing date came faster than any of us expected.

County calendars are like sudden rain—either you’re waiting under clear skies for weeks, or you’re drenched before you can grab a coat.

We put on our Sunday best, which for the Riders means clean denim and jackets that smell like saddle soap. Dee sat with Noah on a bench outside the courtroom and let him twist her ring around her finger like a worry stone.

Inside, the judge listened.

He was kind like good furniture—solid, with a surface that has known cups and elbows.

He asked me questions about schedules and school pickups and what I do when a smoke detector chirps at three a.m. He asked Noah if he wanted to say anything, and Noah shook his head, no words, not here. That was fine.

Marcus stood when it was his turn.

He didn’t make speeches. He said he was showing up to meetings, showing up to work, showing up to the quiet parts of the day.

He said he wasn’t here to pull his boy away today; he was here to stand up straight so his boy could see him from wherever his boy needed to stand. The judge wrote something down then, a little longer than the other notes.

Halfway through, Noah tugged on Dee’s sleeve and pointed at the attorney table. Dee whispered to the bailiff, and the bailiff whispered to the judge, and the judge nodded and said, “Go ahead.”

Noah took his tin and walked to the corner of the table like he was entering a workbench in a shop.

He poured the bolts out—two dozen, maybe more—and began to sort them by size and shine.

He made a square. He made a little line of circles leading to the square like stepping stones. He tapped the line once for each breath. He looked up. “Please,” he said, and no one moved, and he went on. “Don’t… rev my life.”

It wasn’t loud. It didn’t need to be. You could feel the room exhale like we’d all been holding our breath since the door clicked open.

The judge took off his glasses and polished them with the end of his robe in a practiced motion people make when they need to give their face a second to catch up with their heart.

He asked me if I understood the responsibility. I said yes, with more marrow than voice. He asked Marcus if he would work the plan the way we wrote it on the porch. Marcus said yes and held that yes like a full cup.

The judge granted me guardianship with a review schedule and ordered supported contact with Marcus.

He didn’t call it a win.

He called it a beginning.

He asked Noah if he liked engines, and Noah smiled with his whole face, and the judge said he once rebuilt a lawn mower with his granddad and still kept the extra spring in a drawer. “Sometimes the extra piece is the lucky piece,” the judge said. “Sometimes it’s the reminder that things can run fine even if you don’t put everything back the way it was.”

After, in the courthouse parking lot, the Riders held a little ceremony that wasn’t really a ceremony.

We lined our bikes along the curb and turned the keys to ON without touching the throttles. We let the whole row idle for sixty seconds. The sound rolled across the asphalt like distant surf.

Noah stood between me and Snake and counted under his breath. When the minute passed, he put the smallest bolt back into the tin and closed it with a click. “Home,” he said.

We took the long way back to the shop, not fast, just a steady glide through neighborhoods where porch swings creaked and kids chased each other between sprinklers. People looked up when we passed, and they didn’t see a wall of noise. They saw a quiet line holding a lane.