Life after a day like that isn’t a parade. It’s a list on the fridge and a pair of sneakers by the door and a lunchbox on the counter with a tin inside. It’s Tuesday night spaghetti because Tuesday is a good night to have a plan. It’s a checkered calendar with supervised visits that start in a park with a covered pavilion.

It’s Ms. Greene stopping by with a new stack of picture books and a yawn she tries to hide behind a smile.

It’s Marcus showing up with a thermos of coffee for me and a small notebook for Noah because he read that some kids like to draw better than talk. It’s Dee clapping once in the doorway when Noah holds up a tiny bracket he bent himself in a vise, straight as a ruler.

Noah talked more, not in streams, but in good sentences that did what sentences need to do. He told me the difference between the sound of thunder far away and thunder right over the house. He told me the cafeteria smells like pennies.

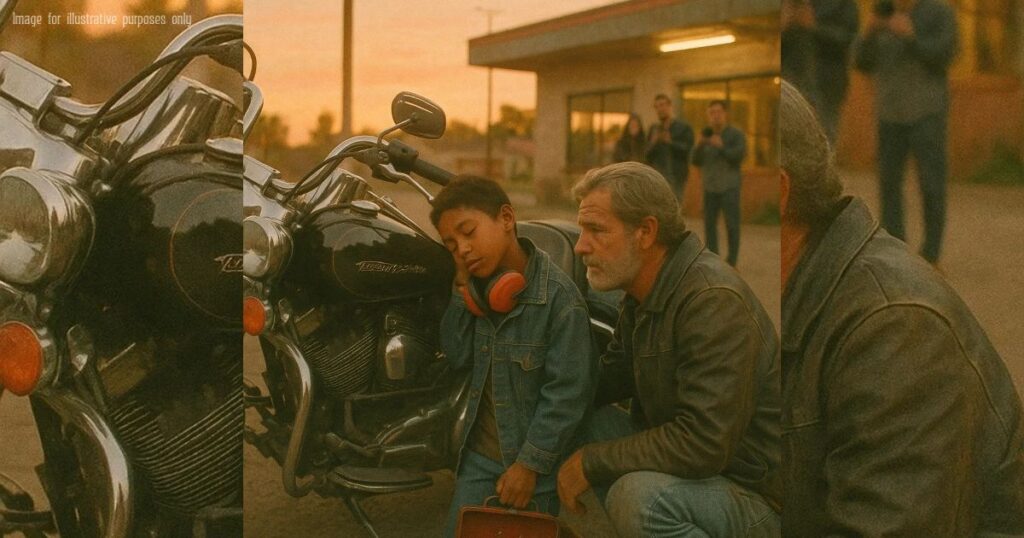

He told me he likes the way the Harley’s shadow looks when we ride past the brick wall on Fifth because it stretches us out like giants but keeps our heads the same size.

He said some words quietly to the engine when he thought I wasn’t listening. I was always listening. That’s what you do when the people in your house are learning to trust the room.

We made a little ritual for hard days. I’d roll Heartbeat halfway out of the garage and set it on the stand, and Noah would stack three bolts on the floorboard like a cairn.

We’d count four in, four out. Sometimes we wouldn’t start the engine. Sometimes idle was a picture on a wall we could stand in front of with our hands in our pockets and our shoulders down.

At school, someone smart noticed that the ear defenders weren’t a crutch; they were a key. They gave him a spot at the end of the lunch table where the noise pressed a little softer.

The vice principal, who rides a Softail on weekends, asked if she could come by and see the club’s backpack drive. On Friday nights, one of the Riders would take a slow loop past the soccer field so Noah could hear the steady hum under the cheer and know that the steady hum would be waiting at home.

Once, late in the fall, Marcus stood in my yard with his hat in his hands again. We watched a line of geese fold into a long V, one bird sliding up to take the front when the leader dipped.

“I’m learning,” he said. “That there are days when the kindest thing is to let someone else pull the air for you for a while.” He looked at me. “Thank you for not making me feel like a wrong note.”

“You’re not a wrong note,” I said. “You’re part of the song.”

He laughed, not loud, but the kind that lightens a person a little. He asked if he could learn to change his own oil. We got on our knees in the driveway and stained our hands on purpose.

Winter came. We hung quilts over the doorways the way my grandmother taught me. On the coldest night, with the furnace humming like a big content animal, Noah put the tin on the coffee table and spilled it in a shine of silver.

He arranged the bolts into letters. H O M E. He took one extra screw—longer than the rest—and tucked it in his pocket. “Lucky piece,” he said with a grin he’d learned in the mirror when he thought no one was watching. “For when school is loud.”

He grew, like kids do when the day isn’t shaking under their feet. He learned where every washer in the shop lived. He learned to set a torque wrench and to stop when it clicks. He learned to wave to the bus driver with his whole arm.

He learned to say you first at the door. He learned that some storms pass, and some storms hang around, and both kinds can be weathered with a plan and a blanket and a sound that knows how to be steady.

When spring finally shook the last frost off the grass, the Second Chance Riders did a charity ride out to the river and back, a route with a graceful loop that feels like turning a page. We put Noah in the middle of the pack with Snake in front and Bear behind so he could feel the safety of a lane made of friends.

He wore an old leather vest one of the ladies had cut down and stitched with a patch that said HOME in thread pulled from my retired work jacket. It was a little crooked, like most true things.

At the halfway stop, an older man with a camera asked if he could take a picture. “It’s for the bulletin board at the rec center,” he said. I looked at Noah. He considered the ground, then nodded.

He held up his tin like a medal.

The picture wasn’t perfect.

The sun flared the lens a little. Someone’s elbow photobombed the edge. You could see a tire mark across my boot and a scrape on Snake’s knuckles. It was better than perfect. It was real.

On the way back, a summer storm built over the west in a dark blue wall. I felt the first fat drops before we hit the hill. We pulled under the old bridge where the graffiti is cheerful, and I lifted my voice so the rain didn’t steal it. “You okay?”

Noah slid his ear defenders into place and set three bolts on the seat. He tapped them four times. “Steady,” he said, and smiled around the edges of the word.

We waited out the worst of it with our jackets over our heads like kids on a porch. When the rain eased to something the road could hold, we kicked stands and rolled slow toward home.

The world was washed and new and smelled like wet leaves and hot brakes and cut grass. We were a small line of engines, not loud, not fast, just exact. A steady hum that you could breathe along to if you needed it.

Back at the house, the porch light threw a circle on the step where the first three bolts Noah ever left for me still sat in a neat little row. I haven’t moved them. Some things you leave where they did their work.

Marcus pulled up a minute later in his old sedan, on time for his visit. He brought a new notebook with a blue cover and three pencils freshly sharpened. He stood on the sidewalk and waited for the nod, and when he got it, he smiled like a man who knows the sound of gratitude when it idles.

Inside, Noah set out his tin on the table and looked up at both of us. “I want to show you something,” he said. He dumped the bolts and sorted and built a tiny bridge between two stacks with a washer in the middle like a safe spot. “This is how you meet in the middle,” he said. “You don’t have to jump. You can walk.”

I don’t know what the years will bring. None of us do. But I know this: there are homes that grow from houses, and homes that grow from habits, and homes that grow from the exact pitch of a sound that stays steady even when the weather turns.

I know the world is kinder when we let our engines idle next to each other for a while and listen.

Some nights, when the shop is dark and the road is a ribbon with no knots, I sit on the step and hear the city breathe. Noah will be inside, tins stacked like treasure, ear defenders hung on a hook by the door like a promise.

The Harley will tick-tick as it cools, a heartbeat moving toward rest. If a car slows out front and someone inside is having a hard day, I hope they hear it—the way a life can hold quiet without breaking, the way a steady sound can carry you until your own lungs remember the count.

And when Noah falls asleep on the couch under the weighted blanket, his hand curled around the lucky screw in his pocket, he sometimes smiles and whispers out of old habit, not to the engine anymore but to the room itself. “Home,” he says.

Then he takes the next breath. And the next. And the next.

Thank you so much for reading this story!

I’d really love to hear your comments and thoughts about this story — your feedback is truly valuable and helps us a lot.

Please leave a comment and share this Facebook post to support the author. Every reaction and review makes a big difference!

This story is a work of fiction created for entertainment and inspirational purposes. While it may draw on real-world themes, all characters, names, and events are imagined. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidenta