Maya pulled a chalk stub from her pocket like a magician produces a coin.

She crouched, considered the ground the way she considers the sky—patient, precise—and drew a spiral in the dust.

It wasn’t perfect.

It didn’t need to be.

Hawk motioned, and two dozen riders set to work in pairs: one carried a bucket of river stones, one placed them along the chalk’s ghost. They moved like a mosaic falling into its destiny.

A police cruiser parked on the street and didn’t approach, just watched.

The officer inside lifted a hand out the window, friendly.

I waved back.

A few teachers stood near the library door, curious, cautious, the way you stand close enough to ask questions but not so close you stop listening.

A boy I recognized from the cafeteria hovered at the far edge, nervous hands buried in his sweatshirt sleeves.

His name was Jude.

He’d gotten the biggest laugh from the table two weeks ago by asking Maya if her headphones were “for aliens.”

My jaw had a memory of clenching at him. He picked up a stone and set it down, then picked up another and set it a little closer to the chalk line.

“Is this right?” he asked Hawk.

“Ask the foreman,” Hawk said, tilting his head at Maya.

Jude looked at her. She pointed with one small finger, millimeters to the left. He nodded and corrected with a seriousness I hadn’t seen in him during lunchtime. They kept working.

In a corner of the courtyard, someone unrolled a plank and printed five words with a woodburner: Silent Thunder Garden — Walk Softly. No logos. No names. No claim of ownership. Only a suggestion.

When the last stone settled, the spiral looked like a question mark that had found peace.

Maya took a step, placed her heel at the starting point, and then stopped.

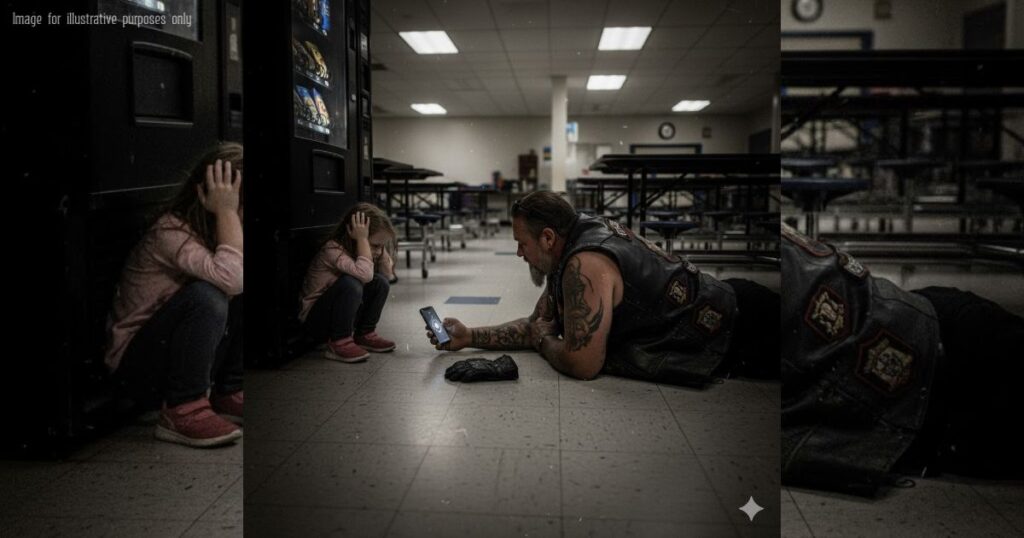

Her fingers fluttered like a moth. Hawk knelt and tapped the rhythm in the air.

She breathed in fours. She set one foot down and then another, following the path with the concentration of a surgeon and the wonder of a small bird discovering lift.

People didn’t clap.

They didn’t whisper.

They didn’t do anything that would turn the moment into something smaller than it was. They just walked beside her without walking beside her—close enough to be company, far enough to let her lead.

Halfway through the labyrinth, Maya paused by the sapling tree that grew out of a square of soil someone had forgotten to cover in concrete.

Hawk reached into his pocket and touched a set of metal tags strung on a chain.

He held them for a long breath, then looped the chain over a low branch. The metal chimed once, and the sound was somehow both heavy and gentle.

“For my boy,” he said, not to anyone, not to everyone. “He liked quiet, too.”

The words took me by the sternum.

I thought about all the ways adults carry storms with dignity, and how sometimes the quietest places are built by people who fought the loudest battles.

Jude stood near Maya at the last turn. He cleared his throat.

“I’m sorry,” he said, and his voice had that raw, uncoached quality that makes you believe it before you decide to. “For saying things. About the headphones. I didn’t know.”

Maya looked at him like she looks at math: a puzzle is only a puzzle until you understand it. “Your apology follows the correct order,” she said. “Thank you.”

“Would you… want me to walk it with you next time?” he asked.

She considered. “Only if you step softly.”

“I can do that,” he said. “I can try.”

Around the edges of the courtyard, a few neighbors who’d worried earlier in the week stood with paper cups of lemonade.

One of them—Mrs.

Moore, who had written three separate comments about noise and parking—brought over a small tray of cookies and murmured that she’d like to volunteer for maintenance duty if someone could write up a schedule.

The principal arrived with a clipboard and a new posture.

She watched three loops of the labyrinth before she spoke.

“You’re right,” she told me.

“We can’t stop drills. But we can do better at what happens after.”

She glanced toward the office window.

“I’ve drafted a plan: designated quiet space, headphones available, optional sensory toolkits. And one more thing. If the riders are willing, we’d like to designate the last Friday of each month for a ‘walk softly hour.’ No engines. Just presence.”

Hawk’s mouth tilted, halfway to a smile and halfway to a promise.

“We can show up without making a show.”

“Thank you,” she said. “We’ll make sure everyone understands this is a cooperative effort. No one is in trouble. There was a misunderstanding.” She looked at me. “Thank you for writing with grace. It helped.”

Maya completed her circuit and placed her hand over the little sign.

Her palm was pale against the dark letters. She turned to me with the kind of smile that starts inside the eyes and only arrives at the mouth when it is sure it will be welcome.

“Quiet can be a shape,” she said.

That night at home, I tucked her in and turned the hallway light down to a whisper. “Did the garden help?” I asked.

“Yes,” she said, already drifting. “The stones keep the noise in lines.”

After she slept, I opened my laptop to find that the same page that had shared the first clip had posted another: a slow, thoughtful video of hands placing stones, a sapling wearing a necklace, a child choosing where the world was allowed to touch her.

The caption this time asked a different question: How do we make room for each other? In the comments, people traded offers—someone could donate mulch, someone else knew a contractor who’d fix the bench for free, another person offered art supplies for students who wanted to paint small spirals on river rocks with their initials.

The next month, “Walk Softly Friday” became a thing.

The riders arrived on foot, rolling their bikes like grand pianos, not like thunder.

Teachers came with coffee and sat on the grass.

The officer in the cruiser parked under shade and waved children across the crosswalk, smiling. Jude brought two friends and whispered to them before they started: “Follow her. Don’t lead.” He said it like a secret rule to get into a better club.

Maya started making little maps of the labyrinth at home, drawing spirals with colored pencils.

She lined them up on the kitchen table in an order only she understood and named them like hurricanes but softer: Pearl, Linen, Daisy, Calm. Sometimes she wore her headphones and sometimes she didn’t.

Sometimes she asked me to tap the metronome on my phone; sometimes she tapped her own wrist.

One afternoon, as winter leaned in and the sun started coming up late to everything, Hawk knocked on our door. He held a small, kid-sized leather vest, plain and simple, no patches, no words. He didn’t ask if she would want it.

He asked if she would like to decide where it belonged.

Maya took the vest and set it on the back of a chair. “It belongs with the garden,” she said. “Not on me. The garden is the person.”

Hawk blinked, then laughed softly like someone finding a penny that used to be theirs.

“Fair point,” he said. “We’ll hang it by the sign. A reminder that strength can be soft.”

We all went together at dusk.

The sapling had grown a little in the months since, enough that its leaves brushed the tags and made a silver sound.

Hawk hung the vest on a simple hook. The leather looked less like armor and more like a promise.

Later, at the edge of the sidewalk, Jude walked up to us.

His mother stood nearby, watching with that very particular relief parents have when they’ve seen their kid try on kindness and decide it fits.

“Miss Harper?” he asked. “Would it be okay if I did my community project on sensory-friendly spaces? I want to interview Maya. If… if she wants.”

Maya looked at him from under her hat. “Questions need to be slow,” she said. “Not like the siren.”

“I can do slow,” he replied. “I can try.”