📖 Part 3 – The Treehouse Ghosts

Harold sat with the phone still in his hand long after the line went dead.

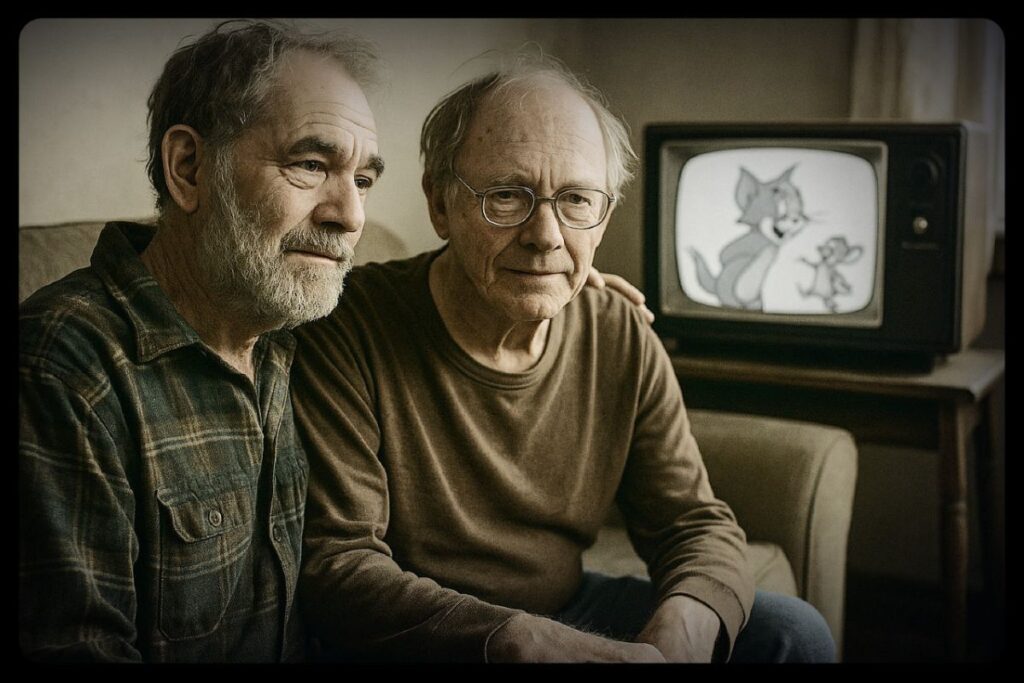

He didn’t call back. He didn’t curse or cry or throw anything, though his hands shook just enough to make the milk crate creak beneath him. The only sound in the room was the slow hiss of the television — like a breath held too long.

Outside, the wind picked up. The swing in the yard began to move. Back and forth. Back and forth.

He looked at the TV and whispered, “Still there, huh?”

For a second, he wasn’t sure if he meant the channel… or the ghost.

He turned off the set, stood up, and stretched until his back popped. The house was quiet. But something in it had changed — like old paint peeling just enough to show the wallpaper beneath. The kind you thought was gone for good.

That night, Harold couldn’t sleep.

He walked barefoot through the house, lit only by the glow of the fridge and a faint porch light. He ended up in the garage, hands drifting over the same boxes he’d ignored for years. One marked “Tommy — 1970s” stopped him cold.

He opened it.

Inside were three things: a cracked baseball signed by Carlton Fisk, a rusted Swiss Army knife, and a folder labeled “Treehouse Plans.”

Harold sat down on the cold concrete floor and opened the folder. Inside were drawings — stick-figure blueprints drawn in childish scrawl, full of ladders that led to nowhere and trapdoors too small for anything but raccoons. There were notes, too:

“Don’t tell Dad we stole the nails.”

“Harold gets the top bunk Tuesdays.”

“If you fall, you gotta pay me your Twinkie.”

He smiled. He could almost hear their voices again — Tommy’s faster, louder, always bossing. Harold’s slower, stubborn, always resisting. But they made it work. For one summer, they were brothers. Not rivals. Not regrets.

Just boys building something together.

The next morning, Harold woke up with dirt under his fingernails.

He’d gone outside before dawn and walked through the wet grass to the old tree. The maple was still there — aged, gnarled, but alive. The treehouse was long gone. Just a few rusted nails still sticking out like lost teeth. But standing there, he could see it again.

The rope ladder. The crooked shutters. The way Tommy used to shout, “All clear!” from above.

Harold pressed a hand against the bark.

“I was mad at you,” he whispered.

His voice cracked.

“I thought you left because of me.”

The wind shifted.

Somewhere, a woodpecker tapped. Somewhere, a memory stirred.

When he walked back to the house, he noticed something strange.

The TV was on.

He was sure he’d turned it off the night before — he always did, part of his bedtime routine. But now it buzzed, screen glowing with a soft, unsteady light. Not static this time. Something different.

Lines. Shapes.

A cartoon.

He leaned in. Couldn’t quite make it out, but he heard it — the tinny jingle of an old commercial.

“Saturday fun on Channel 3 — where brothers laugh and cereal’s free!”

Harold sat down hard on the couch.

This wasn’t just nostalgia.

This was something else.

He reached for the photo album again and flipped to the last page. There, tucked behind a loose flap, was a folded paper he hadn’t noticed before.

It was a letter. Dated August 14, 1989.

Dear Harold,

I didn’t know how to say goodbye, so I didn’t. That was wrong. I’m sorry. I should’ve called after Mom died, but by then we were so far apart I didn’t think I had the right. I want to come back someday, if the treehouse is still there. If not… maybe we can build something new.

Love, Tommy

Harold stared at the paper for a long time. Then folded it slowly, carefully, like he was holding something sacred.

He looked at the TV again.

The cartoon had ended. The screen went dark.

But not before a final image appeared — just for a moment.

Two boys on a swing set, one pushing the other higher.

And a line of text below it:

“Channel 3 remembers.”

Harold wiped his eyes.

Then stood up.

He knew what he had to do.

He went to the garage, pulled out the hammer, the toolbox, and the leftover lumber from last winter’s failed porch project. The tree wasn’t what it used to be, but neither was he.

Didn’t matter.

He was going to rebuild the treehouse.

And this time, he wouldn’t build it alone.

📖 Part 4 – A Hammer and an Invitation

The first nail bent sideways.

Harold muttered under his breath and pulled it out with a grunt. His joints didn’t move like they used to. Every step up the ladder sent his knees creaking, and his shoulders protested every time he lifted the hammer.

But he kept going.

One plank at a time.

By noon, he had a frame. Rough. Crooked. But standing. He sat on the middle rung of the ladder and wiped the sweat from his brow with the hem of his flannel shirt. The tree rustled overhead, leaves whispering like an old friend offering encouragement.

He hadn’t built anything in years.

Not since the porch. Not since the fence that rotted faster than he’d expected. Not since Tommy.

That afternoon, Harold walked into town — something he hadn’t done in weeks.

Downtown Belfast was quiet, just a few folks milling about the hardware store and the bakery with its faded blue awning. He stopped at the corner shop for more nails and a new level. The clerk, a kid maybe twenty-five, looked up from his phone as Harold set the items down.

“Building something?” he asked.

“Treehouse,” Harold said. Then added, “Rebuilding, really.”

The kid blinked. “For grandkids?”

Harold hesitated. “For someone I owe a long-overdue Saturday morning.”

He walked out before the kid could ask more questions.

Back home, the second layer of planks came together easier. He remembered things — tricks Tommy had taught him, like how to square corners with just a bit of string and a carpenter’s pencil. He even whistled a little, though it came out more like a wheeze.

When he went inside for the night, the TV was on again.

This time, it showed an old commercial: a boy chasing a dog through a field, both laughing, both timeless.

And a voiceover:

“The best memories never really fade. They’re just waiting for you to turn the dial.”

Harold sat down, eyes wet, lips parting with a chuckle.

“You always were the sappy one,” he whispered.

Then he did something he hadn’t done in 20 years.

He wrote a letter.

Thomas E. Dunn

Akron, OH

Tommy,

You hung up before I could say it — I don’t blame you. I was angry too, for too long. But I found your letter. The one you left in the album. You wanted to come back if the treehouse was still here. Well, it’s not. But I’m building it again. Not perfect, but sturdy enough to sit and remember.

Come home if you want. Come laugh, even if just once.

I’ll be on the swing set at noon this Sunday, like the old days.

– H.

He folded it with care and sealed the envelope, hand trembling slightly as he pressed the stamp into place. He drove to the post office the next morning — first time behind the wheel in weeks — and mailed it without hesitation.

Then he waited.

Three days passed.

He built a ladder.

He painted a sign that read:

“DUNN’S DEN – MEMBERS ONLY.”

Just like they used to call it.

He even found an old transistor radio in the shed and rewired it to play one station that still spun 70s vinyl.

But by Saturday night, there was no reply. No letter. No call. No sign.

Sunday came cloudy and cool.

Harold put on his best flannel. Brushed his thinning hair. Sat on the swing set at noon.

No Tommy.

He waited an hour.

Then another.

He stood to go — heart low but not bitter — when he heard a sound behind him.

Gravel crunching.

A car door closing.

And then — a voice, older, softer, but unmistakably familiar:

“…You still hog the good swing, huh?”

Harold turned.

And there he was.

Tommy. Hair thinner, shoulders stooped, wearing the same crooked smile he had when he was ten and full of bad ideas.

They stared at each other for a long, quiet moment.

Then Harold stepped forward.

And said only what mattered:

“You came back.”

Tommy nodded. “Took me a while. But yeah… I’m here.”

Harold motioned to the treehouse.

“Still a few boards left. Could use a hand.”

Tommy smiled.

“Only if I get Tuesdays on the top bunk.”