I never thought an old letter could make my hands shake again.

But there it was—creased, yellowed, the envelope still smelling faintly of bamboo smoke.

It came in the mail last week, no return address. Just my name, my rank, and a language I hadn’t seen in fifty years.

Vietnamese.

My wife found it first. I told her it was probably a mix-up. But I knew better.

Part 1: The Memory Opens

My name’s Frank Delaney.

Sergeant, Charlie Company, 25th Infantry Division, 1968.

Now I’m just an old man with stiff knees and a truck that needs more oil than gas. I live on the edge of Keystone, Missouri, near a little Baptist church with a steeple that still rings on Sundays. Most days, I sit on my porch with a black coffee and the dog tags I never had the heart to put away.

I don’t talk much about the war. Folks in town know I served, but they don’t ask questions—and I don’t offer answers. That’s how it’s always been. Quiet understanding. Veterans don’t need to speak everything out loud. Some things stick better when they stay buried.

But this letter…

This one didn’t want to stay buried.

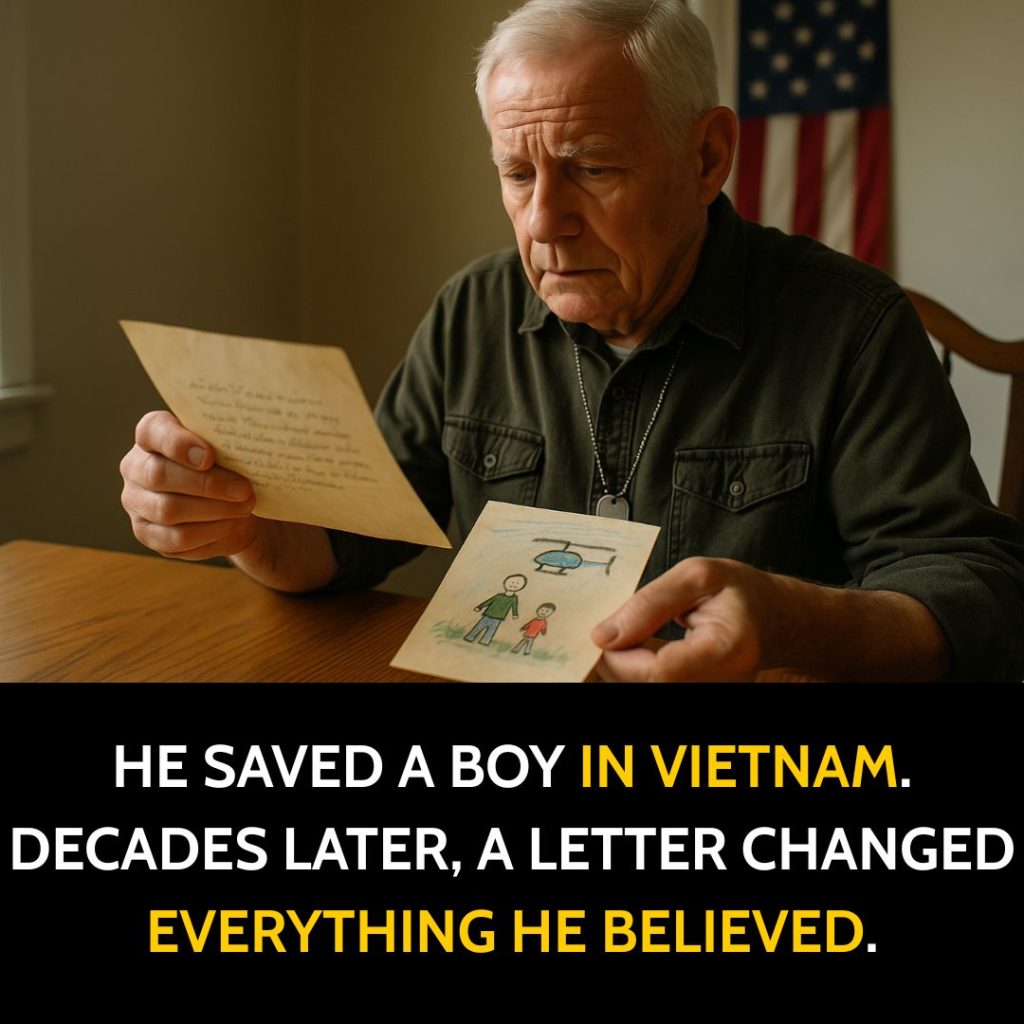

The handwriting was careful. Childlike, maybe. Or just someone doing their best in English. The paper was folded around a small drawing, drawn in colored pencil—green hills, a black helicopter, and two stick figures. One bigger than the other. Both smiling.

Tucked in the corner of the picture, in small, slanted print:

“Thank you, American soldier. You saved my mama. I never forgot.”

That was it.

No name. No date.

Just that picture. And a weight I hadn’t felt in years.

There’s a moment from the war I never told anyone about. Not even Susan, not even the chaplain. A firefight near a small village just north of Pleiku. We were pinned down. I remember the smoke. The screaming. And a little boy, no older than six, running out of a hut toward the gunfire.

I didn’t think. I just ran. Hauled him back behind a broken wall, dropped him with his mother, and went back to my position.

It was a blur. One of those things that happens before your brain can catch up.

I didn’t know they lived. I didn’t know anything, really.

Until now.

That letter has been sitting on my kitchen table for five days. I keep reaching for it, like maybe touching it again will make it clearer.

Why now? After all these years?

Did he mean for me to find peace? Or was he just reminding me of something I tried to forget?

I’m not sure. But I can feel something shifting. Like the story isn’t over.

Maybe it never was.

Part 2: What Was Buried

The letter sat unopened for five days.

Now it won’t leave my thoughts.

I didn’t go looking for the past—but the past found me anyway.

That village, the one near Pleiku… it comes back to me sometimes in dreams. Not like a movie. More like flashes. Smoke. A red roof. The snap of AK fire over banana trees. A woman crying behind a crumbling wall.

We were sweeping the area after a bad ambush on Route 19.

It wasn’t supposed to be anything more than recon.

But that’s the lie of war—there’s no such thing as “just recon.”

I was twenty-one. Strong, stupid, and angry. We were scared most of the time, but didn’t show it. We joked, we smoked, we spit on the ground like we owned it. That day, we were ten minutes from pulling out when everything went to hell.

The shot hit Stevens first—right in the neck.

Then it was chaos. Bullets kicking up dirt. One of our guys screaming about a tree line. Someone shouting for cover. I remember the sound of the M60 chewing through bamboo.

And in the middle of it all, a boy.

He must’ve slipped out of a hut when the shooting started. Small, barefoot, wearing a red shirt. He was crying, running right toward us—toward the bullets. And then I saw her—his mother—reaching, screaming, but trapped behind a wall of fire.

I don’t know what made me move.

I just did.

I dropped my rifle, sprinted into the open like a damn fool.

Threw my body over that kid and dragged him toward a stack of fallen clay bricks. His mother ran to us, blood on her face, yelling something I couldn’t understand. I shoved the boy into her arms and turned to get back.

A round clipped my shoulder.

They said I was lucky.

The doc patched me up and gave me morphine.

The lieutenant wrote me up for a Bronze Star. I tossed the paperwork in a footlocker and never spoke of it again.

I didn’t feel brave. I felt stupid. And sore. And guilty.

Because a week later, Stevens died.

And every time I think of that boy, I see Stevens lying in a green poncho, zipped up, ready for the bird home.

I saved someone I didn’t know—and lost someone I did.

Tell me how to square that.

The preacher at Oak Hill Baptist talks about forgiveness like it’s easy.

He reads, “Cast all your anxiety on Him because He cares for you.”

Well, I tried. But there’s a part of me that never could hand it over.

I carried that memory like a rusted dog tag.

Hidden, but always there.

Susan knew better than to push. She married a man who woke up sweating and flinching at thunder. A man who still folds his clothes military-style and checks door locks three times before bed.

She loved me anyway.

Last night, I finally took the drawing from the envelope.

Really looked at it.

Two stick figures: one big, one small.

Smiling.

I hadn’t smiled like that in years.

And then I noticed something I hadn’t before. On the back of the paper, faint and written in Vietnamese, were six small words—and one English phrase.

Susan looked it up for me, bless her heart.

It read: “He ran into fire for me.”

And beneath it:

“Please, if you are still alive—write back.”

I haven’t written a letter in decades.

But I think it’s time.

Because somewhere across the world, a man remembers a moment I tried to forget.

And maybe, just maybe…

we both need to remember it differently.

Part 3: What Still Matters

This morning, I stood where it all happened—

Not in Vietnam, but right here, on my back porch, holding that same letter in both hands.

Fifty years later, and my knees still shook like they did behind that wall of clay bricks.

After I read the words again—“He ran into fire for me”—I did something I hadn’t done since I left the Army.

I prayed out loud.

Not fancy, not the way the preacher does.

Just me and the kitchen table, my palms flat on the wood, my voice quieter than a whisper.

“Lord, if there’s still something I need to do… show me.”

The next morning, I took out an old shoebox where I kept things I thought I’d never need again.

My Bronze Star certificate.

A photo of Charlie Company, smudged and soft at the edges.

A snapshot of young Stevens, smiling with his helmet pushed back, cigarette in his teeth.

And then I wrote back.

The letter wasn’t long. Just honest.

“I remember you.

I didn’t know if you made it.

I hoped you did.

I’m sorry it took me so long to answer.

You saved something in me too.

—Frank Delaney, Charlie Company, 25th Infantry, 1968.”

Susan mailed it with trembling hands. I didn’t ask her to. She just knew.

Two weeks passed before a package arrived.

Postmarked from California. Vietnamese return address.

Inside was a photo. A man, about my age, standing beside a small church built on the edge of a rice field.

Behind him, a plaque.

Written in both languages.

“In memory of the American soldier who carried a boy from fire.

May peace always follow where courage once walked.”

There was no name signed, just a note:

“You did more than save a life.

You gave me a reason to live mine.

I named my first son after you.”

I must’ve read that line a hundred times.

That night, I sat on the porch with my old boots on and the dog tags around my neck. I hadn’t worn them in years. The Missouri sky was quiet. The same kind of quiet I used to fear—before I knew it could be holy.

I thought of Stevens. Of the young boy. Of the weight we carry and the grace that sometimes finds us anyway.

And I thought about what matters now.

This morning, I went to the small hill behind Oak Hill Baptist, where the veterans are buried. I brought the photo with me. I didn’t say much—just pressed it against Stevens’ stone for a moment and said:

“He lived, brother. We didn’t go through that for nothing.”

Then I planted a bamboo seedling. Just one.

Right next to the flagpole.

It might not grow well here, but that’s not the point.

The point is—I did something with what I was given.

And for the first time in a long while… I felt free.

Some letters take a lifetime to arrive.

But when they do, they carry more than words.

They carry truth.

And maybe even healing.