The note that saved a boy’s life wasn’t flagged by a safety algorithm. It wasn’t caught by a keyword filter. It was scribbled in faint, erasable pencil on the back of a pop quiz, invisible to a scanner, right next to a wrong answer about The Great Gatsby.

If I had done what the district wanted—if I had used the “auto-grade” feature on the new tablets—that quiz would have been processed in three seconds. The boy, a quiet sophomore named Leo who wore the same gray hoodie every day, would have received a 60%. The system would have recommended remedial reading modules.

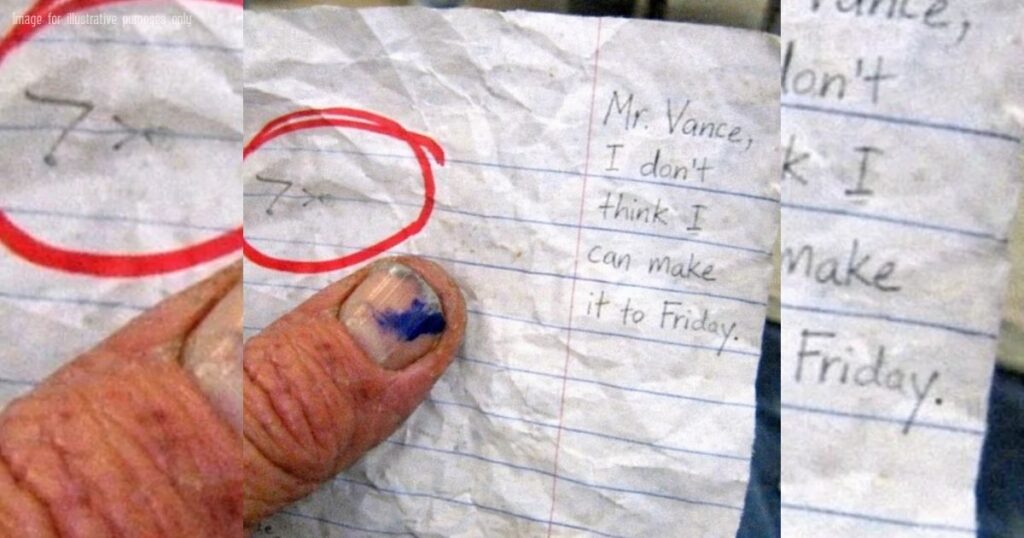

But I don’t use the auto-grade. I use a red felt-tip pen. And because I was looking at the paper with my own tired, straining eyes, I saw the tiny, trembling letters Leo had written in the margin: “Mr. Vance, I don’t think I can make it to Friday.”

I was thinking about Leo as I sat in the windowless auditorium of the district headquarters. The air conditioning was humming a low, aggressive drone that made the room feel like a meat locker.

On the stage, a man named Dr. Sterling was pacing back and forth. He was our new Superintendent of Innovation. He wore a smartwatch that probably cost more than my first year’s salary, and he spoke with the energetic bounce of a man who had never tried to teach Romeo and Juliet to a room full of hungry, heartbroken teenagers on a rainy Tuesday.

“The future of education is frictionless,” Sterling announced, clicking a remote. A massive graphic appeared on the screen behind him. It showed a student’s head connected to a cloud icon. “With the rollout of ‘Apex-Learning 4.0,’ we are finally eliminating the bottleneck of human delay. The AI assesses proficiency in real-time. It creates a personalized pathway. It frees you, the teachers, from the drudgery of grading so you can focus on… facilitation.”

Facilitation. That was the new word. We weren’t teachers anymore. We were “Instructional Facilitators.”

I looked down at my hands. They were stained with blue ink from my fountain pen. I’m sixty-two years old. I have chalk dust permanently settled in the creases of my knuckles. I’ve taught in this district for thirty-five years. I remember when we had textbooks that fell apart if you opened them too fast. I remember when we had to buy our own fans in September.

But mostly, I remember the kids.

I looked around the room. Three hundred teachers sat in silence. I saw Sarah, a brilliant history teacher, rubbing her temples. I saw David, a math wiz who used to play guitar for his homeroom, scrolling through job listings on his phone under the table. We were all demoralized. We were being told that our intuition, our experience, and our connection to the students were “inefficiencies” to be optimized out of existence.

“By shifting to this adaptive model,” Sterling continued, his voice booming, “we project a 30% increase in standardized test throughput and a significant reduction in staffing costs over five years. We are removing the variable of subjective bias.”

Subjective bias.

That was the phrase that made me stand up.

My lower back popped. My knees groaned. I wasn’t trying to make a scene; I just couldn’t sit there and let him call my life’s work a “variable.”

“Excuse me,” I said. My voice wasn’t loud, but in the dead silence of that room, it carried.

Dr. Sterling stopped mid-stride. He looked at me, shielding his eyes from the stage lights. “We’ll have a breakout session for questions later, sir.”

“I’m not asking a question,” I said, stepping into the aisle. “I’m offering a correction.”

I walked toward the front. I don’t walk fast these days, but I walk with purpose. I could feel the eyes of the young teachers on me—the ones who are drowning in paperwork and fear, the ones who are quitting within their first three years.

“You used the word ‘bias,'” I said, facing the stage. “And you talked about ‘frictionless’ learning. I want to tell you about friction.”

I turned to look at the room, then back at Sterling.

“Last week, I assigned an essay on To Kill a Mockingbird. A student submitted a paper that was perfect. The grammar was flawless. The structure was impeccable. The thesis statement was strong. Your ‘Apex’ system would have given it an A-plus instantly.”

I paused.

“I gave it a D.”

Sterling smirked. “Well, that sounds like exactly the kind of subjective grading we are trying to eliminate.”

“I gave it a D because it wasn’t his voice,” I said, my voice rising. “I’ve known this student for two years. I know he loves baseball and hates adverbs. I know he struggles with run-on sentences when he gets excited. The paper he turned in was generated by a chatbot. It was soulless. It was technically perfect and humanly empty.”

I took a breath.

“So, I didn’t grade it. I sat him down. I created ‘friction.’ We talked for an hour. I found out his parents are going through a violent divorce and he hasn’t slept in three days. He used the bot because he was too exhausted to think. We didn’t talk about the book. We talked about how to survive the night. I got him to the counselor. He cried. I listened. That is the job.”

I pointed at the giant screen behind Sterling, at the cold, clean lines of his data graph.

“Your software can count how many commas a student uses. But can it tell if a child is hungry? Can your algorithm detect the difference between a student who is lazy and a student who is working a night shift to help pay their family’s rent?”

The room was electric now. The silence had changed. It wasn’t the silence of boredom anymore; it was the silence of people holding their breath.

“You want to prepare them for the real world?” I asked. “The real world is terrified. The real world is lonely. These kids are growing up in a time where everyone is shouting and no one is listening. They are addicted to screens that tell them they aren’t good enough. The last thing—the absolute last thing—they need is another screen judging them.”

I looked at the young teachers in the front row.

“They need eye contact,” I said softly. “They need to see us make mistakes on the whiteboard. They need to see us laugh. They need to know that when they fail, a human hand will be there to help them up, not a notification ping.”

“Sir, you are out of order,” Sterling snapped, his smile gone. “This is a mandatory training on district policy.”

“It’s a funeral for the profession,” I said. “And I won’t be a pallbearer.”

I picked up my bag. It was an old leather satchel, battered and scratched, filled with unread essays and half-eaten apples.

“I’m going back to my classroom,” I said. “I have a stack of journals to read. Hand-written. Illegible. Messy. And beautiful. Because that’s where the truth is. The truth is in the margins.”

I turned and started the long walk up the aisle toward the exit doors.

For five seconds, the only sound was my footsteps on the carpet.

Then, I heard it.

Snap.

It was the sound of a notebook closing.

I heard the squeak of a sneaker. Then the clatter of a chair.

I didn’t look back, but I could hear them. One by one, then ten by ten. The rustle of coats. The zipping of bags. The English department. The Science department. The Special Ed teachers who have the hardest job on earth.

They were standing up.

When I pushed open the double doors into the hallway, a young woman caught up to me. It was Ms. Miller, a second-year teacher who I knew had been crying in her car during lunch breaks.

She was trembling, but her head was high.

“Mr. Vance,” she whispered. “I was going to quit today. I had my resignation letter in my bag.”

She reached into her purse, pulled out a crisp white envelope, and ripped it in half.

“I thought I was failing because I couldn’t keep up with the data entry,” she said, tears welling in her eyes. “I forgot why I wanted to do this.”

I smiled at her. It was a sad smile, but it was genuine.

“We can’t stop the future, kid,” I told her. “The tablets are staying. The budget cuts are staying. The world is getting faster and colder.”

I put a hand on her shoulder.

“But a machine cannot build a legacy. A microchip cannot comfort a child who has just had their heart broken. That is our territory. We are the keepers of the light. Don’t let them dim you.”

We walked to the parking lot together. The sun was setting, casting long, golden shadows across the asphalt. It looked like the end of something, but for the first time in a long time, it also felt like a beginning.

Here is what we must remember:

We are building a society obsessed with speed, metrics, and optimization. We want education to be downloadable and success to be quantifiable.

But you cannot automate inspiration. You cannot optimize the spark that happens when a child finally understands a concept they’ve been fighting for weeks.

When a student looks back on their life, they won’t remember the educational software that tracked their reading speed. They won’t remember the frictionless interface.

They will remember the teacher who noticed they were fading. They will remember the adult who looked them in the eye, ignored the bell, and asked, “Are you okay?”

Technology is a tool. Teachers are the heartbeat.

Let’s stop trying to code the humanity out of our classrooms, and start fighting for the connection that makes us human in the first place.

—

PART 2 — “The Day the Speech Went Viral (and the Kid I Was Trying to Save Disappeared)”

By the time I got home that night, my old flip-style phone—yes, I still carry one—was vibrating itself off the kitchen counter.

It wasn’t one call.

It was a swarm.

Voicemails. Texts. Emails I didn’t know I could receive on a device that simple.

And one subject line, repeated like a chant:

YOU’RE TRENDING.

I stood there in my dim kitchen, still smelling like auditorium carpet and stale coffee, and stared at my hands like they belonged to someone else.

Click the button below to read the next part of the story.⏬⏬