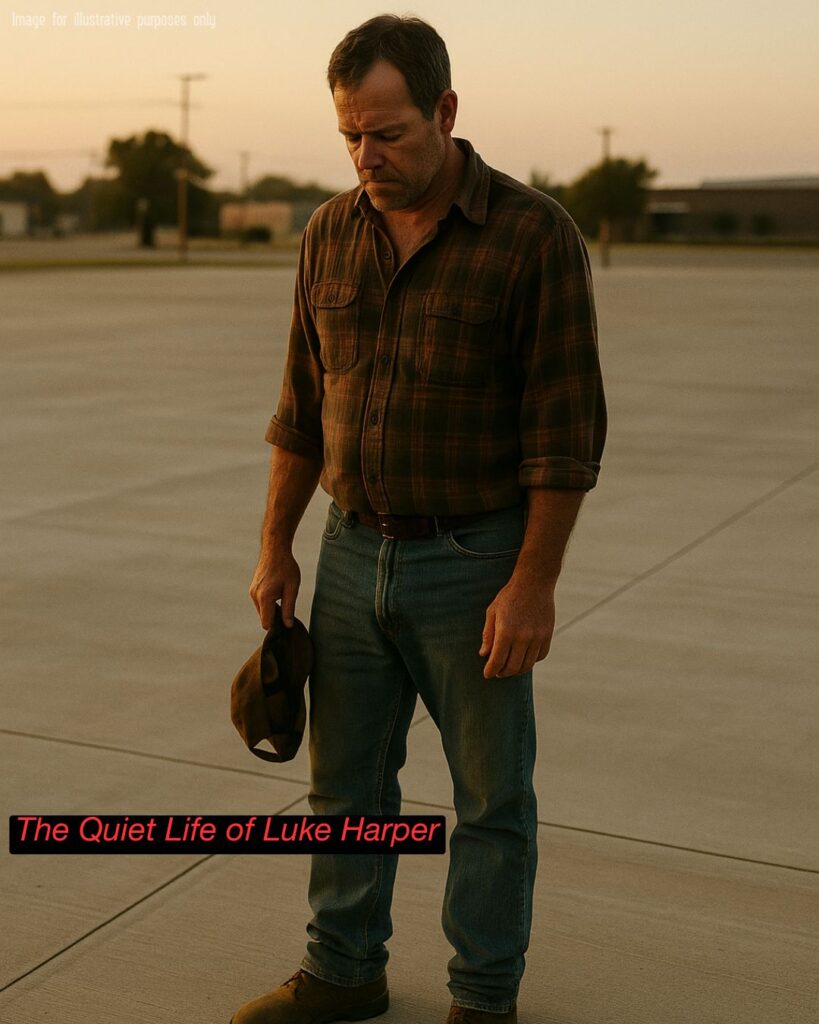

PART 3 — “The Year They Paved the Feed Store Lot”

They paved over the feed store lot in ’97, and I swear to God, it felt like a funeral for the last honest place in town.

Back then, the feed store wasn’t just where we bought corn mash and chicken grit.

It was where men leaned on the tailgates of rusted pickups, boots coated in clay, talking weather and politics like either could be predicted. It was where I learned to tie a square knot from Old Man Crawley, who had one eye and a voice like he’d swallowed gravel.

It smelled like molasses, diesel, chew tobacco, and dust — the kind of scent you only miss once it’s gone. Like your dad’s shirt after he dies. Like the barn when it’s empty.

I was 14 when Daddy let me drive the truck into town alone for the first time. Told me to pick up three sacks of feed, a spool of barbed wire, and “no damn soda unless you’ve already loaded the bed.”

I remember how my hands shook on the wheel. How I tried to stand a little taller, walk a little slower when I climbed the steps of Harper & Sons Farm Supply. (No relation — different Harper.)

The man behind the counter wore suspenders, chewed gum like it owed him something, and nodded once. That nod was enough. You didn’t need small talk at the feed store. Just cash, grit, and your own damn list.

Over the years, the names changed, but the place didn’t.

Even when Walmart came. Even when they built that gleaming tractor dealership out on Route 60. The old feed store stayed the same — bent siding, hand-painted signs, and a porch that groaned when you stepped on the third board from the left.

I brought Hank there once.

This was before his leg went bad, back when he was still just a beat-up mutt I hadn’t named yet. He hopped into the cab like he’d been doing it his whole life and laid his head on my lap while I drove.

When we pulled up, a group of old-timers on the porch stopped talking.

One of them — I think it was Elmer Watts — pointed to Hank and said, “Looks like you got yourself a damn fine dog.”

And just like that, Hank became mine.

That’s how things worked at the feed store. Dogs were claimed. Advice was given. News spread without needing a phone. If you wanted to know who lost a calf, who sold their land, or who buried a wife, you came there.

But in ’97, things changed.

They poured concrete over the gravel lot — smooth, pale gray, like a parking lot in the city.

I remember driving up, expecting the usual crunch under my tires. Instead, I rolled quiet.

Too quiet.

Inside, the shelves were neater. The coffee pot was gone. The new owner wore a polo shirt and asked if I had a rewards card. A rewards card. At a feed store.

I didn’t say anything. Just grabbed my wire, paid in cash, and walked out.

Elmer wasn’t on the porch.

Neither was the third board that groaned.

That was the same year the co-op shut down, and the same year Ruthie moved to Tulsa “for better schools.” It was the year Hank started limping bad, the year corn prices crashed, and the year I caught myself staring at the sky too long, wondering if I’d missed something.

I think that’s the year I stopped feeling young.

I used to believe hard work was enough.

You put your back into it, keep your head down, and the world lets you stay standing.

But I’ve learned that life isn’t just a field to plow. It’s a barn that leans. A tractor that won’t start. A feed store that turns into a chain.

They say progress is good.

I say not all footprints deserve to be paved over.

There’s an old-timer who still remembers me from back then. Joe Reynolds — runs a tiny produce stand now near the post office.

I stopped by last fall to grab a few ears of corn.

He handed me a bag and said, “You still got that dog with the limp?”

I didn’t answer right away.

Just nodded once.

Like we used to.

Sometimes I think about the people who never got to feel a place like that.

Folks now, they go from screen to screen. Order feed online. Watch weather apps instead of reading the sky. Talk about farming in hashtags. They’ve never waited on the porch while someone scooped your oats by hand.

They’ve never watched a man roll a cigarette with fingers that buried his father and planted the same row of beans fifty years in a row.

They’ve never known the quiet glory of being trusted without needing to explain a damn thing.

I’m not saying the past was perfect.

Hell, we had our share of hard years — droughts, floods, engine trouble, busted knees, broken hearts.

But back then, people shook your hand with both eyes open. You didn’t need a lawyer to mean your word. And if you had a dog with a limp, no one asked you to put him down or leash him up — they just patted his head and made space on the porch.

So what did I learn, in the shadow of a feed store they paved over?

That some things you can’t buy back.

That worth isn’t measured in efficiency.

That the best lessons don’t come from books or schools or Zoom calls — they come from watching how a man stacks hay, how a woman sets a roast pan down, how a dog waits by the truck bed without being told.

That the world may keep spinning fast — but it’s the still places, the gravel-scratch moments, that stay with you.

And if you ever find yourself lost in this loud, shiny world?

Remember this:

The ground that matters most is the kind that sticks to your boots.

The kind that remembers who stood on it, who loved on it, and who didn’t ask for much — just a tailgate, a clean sky, and a place to call their own.