My father hasn’t admitted to a single weakness since 1984. So when he whispered my name over the phone, I didn’t just hear fear—I heard the sound of a mountain crumbling.

I’m a thirty-eight-year-old data analyst living in a glass high-rise on the East Coast. My life is measured in spreadsheets, quarterly projections, and video conferences where everyone smiles but no one says anything true. I pay for a gym membership to lift heavy things because my life requires zero physical effort.

My father, Frank, is the opposite. He’s seventy-two, a retired millwright living in the Rust Belt, in the same drafty house where I grew up. He measures his life in calluses, welded joints, and the things he built with his own two hands. He believes that if you can’t fix it yourself, you don’t deserve to own it.

That’s why the call terrified me.

It was 10:00 AM on a Tuesday. My phone buzzed against the mahogany conference table. “Dad.” He never calls during work hours. He thinks “office jobs” are fake, but he respects the clock.

I stepped out, my heart hammering against my ribs. “Dad? Is everything okay?”

There was a long silence on the other end. Just the static of a landline and a shaky breath.

“Ben,” he said. His voice, usually a deep baritone that could cut through the noise of a factory floor, sounded thin. Like paper. “I think… I think it’s time to sell the truck.”

I froze. The Truck. A 1978 heavy-duty pickup, painted a faded midnight blue. It wasn’t just a vehicle; it was the third member of our family. He had bought it fresh off the line the year he made foreman. He had driven me to Little League in it, moved me into college with it, and drove it to my mother’s funeral. That truck was his independence. It was his proof that American steel lasts forever.

“Sell it?” I asked, confused. “But you just spent six months sourcing that vintage carburetor. You said you were going to restore it for the summer parade.”

“I can’t finish it,” he mumbled. “It’s the starter motor. The bottom bolt. It’s rusted shut. I’ve been under there for two days, Ben. My hands… they just won’t grip the wrench anymore. I dropped it on my face this morning.” He let out a dry, bitter laugh. “I’m useless, Benny. If a man can’t turn a wrench on his own truck, he’s just taking up space.”

I looked back at the glass doors of my office, at the young interns laughing over oat milk lattes, at the graphs on the screen that meant nothing.

“Don’t do anything,” I said. “I’m coming home.”

“No, you have work. Gas is expensive. Don’t be—”

“I’m coming home, Dad.”

The drive took five hours. I watched the landscape change from the manicured suburbs of the coast to the rolling, gray hills of the heartland. I passed closed factories with shattered windows, main streets that had become ghost towns, and billboards fading under the winter sun. It was a part of the country that felt like my father: proud, battered, and slowly being forgotten by a world that moved too fast.

When I pulled into the gravel driveway, the garage door was half-open.

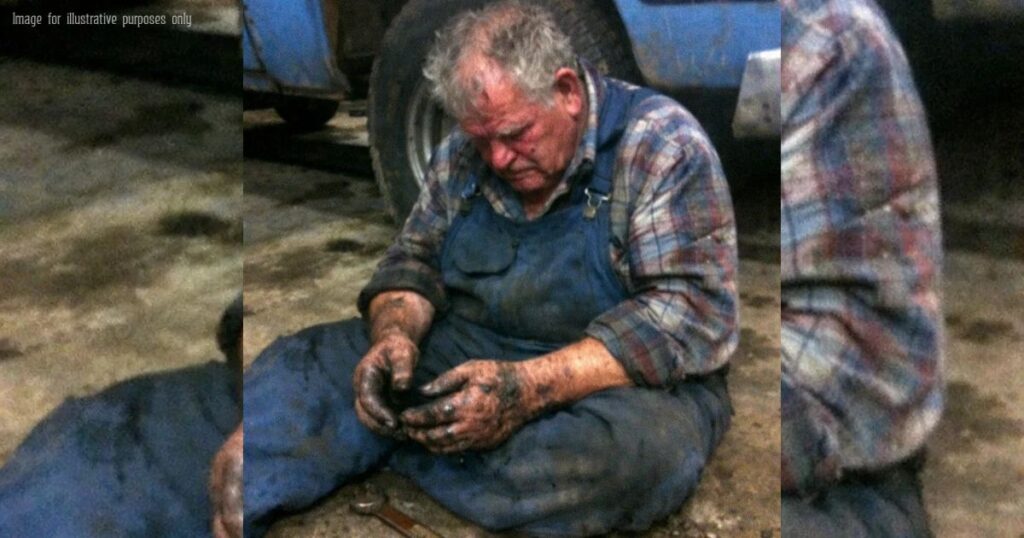

I found him sitting on an overturned bucket next to the truck. He was wearing his old grease-stained coveralls. He looked smaller than I remembered. His knuckles were swollen, red and angry from the arthritis he refused to treat.

“You drove five hours for a stuck bolt,” he grunted, not looking me in the eye. He was ashamed. In his code, needing help was a sin.

“I drove five hours because I wanted a beer with my dad,” I lied. “And maybe I want to learn how to swap a starter. You never taught me that one.”

He looked up, skeptical. “You? You make money by typing. You have soft hands, Ben.”

“Then get me some gloves.”

I took off my tailored jacket and rolled up my pristine white sleeves. The garage was freezing, smelling of gasoline, old rubber, and sawdust—the perfume of my childhood.

I slid under the truck. The concrete was ice-cold against my back. The undercarriage was a maze of rusted metal and grime. I found the starter motor. The bolt was there, seized by forty years of oxidation and road salt.

“Okay,” I yelled from underneath. “I’m in position. What now?”

“It’s a three-quarter inch socket,” Dad called out. His voice was stronger now that he was giving orders. “You can’t just muscle it, Ben. You’ll strip the head. You have to feel the metal. Rock it back and forth. Let it know you’re there.”

I fitted the wrench. I pulled. Nothing. It was welded solid by time.

“It’s not moving, Dad!”

“Stop pulling like a damn gorilla!” he snapped. He shuffled over and laid down on the cardboard next to me. “Here. Give me your hand.”

He placed his large, trembling hand over mine on the handle of the ratchet. His skin was rough like sandpaper, warm and dry.

“Close your eyes,” he whispered. “Don’t look at the bolt. Feel the tension. Apply pressure… now stop. Feel that? That little give? That’s the rust breaking, not the metal. Now, breathe out and push.”

We pushed together. My strength, his technique. My young muscle, his old wisdom.

Crack.

The sound was like a gunshot in the quiet garage.

“It broke?” I panicked.

“No,” Dad whispered, and I could hear the smile in his voice. “It surrendered.”

It took us another hour to swap the part. My knuckles were bleeding, my white shirt was ruined with black grease, and there was dust in my eyes. I had never felt better in my life.

When we finished, Dad climbed into the driver’s seat. “Stand clear,” he commanded.

He turned the key.

The engine didn’t just start; it exploded into life. A deep, guttural roar that shook the tools on the workbench. It was the sound of history refusing to die. The smell of unburnt fuel filled the air, intoxicating and victorious.

Dad revved the engine once, twice. He shut it off and stepped out. He wasn’t looking at his shoes anymore. He was standing tall. The shame was gone, replaced by the quiet dignity of a job done right.

We sat on the tailgate of the truck as the sun went down, drinking cheap domestic beer that tasted like water and metal.

“I thought I was done,” Dad said softly, tracing the rim of the can. “The world… it’s got so complicated, Ben. Everything is digital. Everything is ‘smart.’ My TV has more buttons than this entire truck. I feel like… like a rotary phone in an iPhone world.”

He looked at his hands. “When I couldn’t turn that bolt, I thought, ‘That’s it. I’m obsolete.'”

I took a sip of beer, looking at the man who taught me how to shave, how to throw a spiral, and how to be a man.

“Dad,” I said. “I might know how to code, and I might know how to navigate a spreadsheet. But if the power goes out? If the server crashes? I’m useless. You built this. You understand how the world actually works.”

I pointed to the tool chest. “I provided the torque today. That’s it. But you knew where to apply it. Strength is cheap. Knowing where to push? That’s rare.”

He stayed silent for a long time. Then, he reached into his pocket and pulled out his favorite pocket knife—a bone-handled tool he’d carried since Vietnam. He placed it in my hand.

“Keep it sharp,” he said.

“I can’t take this, Dad.”

“Take it. Put it in your desk drawer at that fancy office. Use it to open your Amazon boxes or whatever.” He grinned. “Just remember, sometimes you have to cut the tape yourself.”

I drove back to the city late that night. My hands were stained with grease that no amount of soap could scrub away entirely. I gripped the steering wheel, thinking about the millions of men and women like my father across this country.

We think they are aging out. We think they are stubborn, outdated, or “behind the times” because they can’t navigate a touchscreen menu or understand the latest social media discourse. We get frustrated when they ask for help with the Wi-Fi.

But we are missing the point.

They aren’t breaking down because they are weak. They are breaking down because they feel unnecessary. They spent a lifetime being the providers, the fixers, the builders. And now, they sit in silent houses, feeling like the world has moved on without saying goodbye.

My father didn’t need a mechanic. He didn’t need me to buy him a new truck. He needed to know that he was still the foreman. He needed to know that his hands—those battered, beautiful hands—still held value.

If your parents call you this week with a “stupid” problem—a leaky faucet, a remote control that won’t work, a heavy box they can’t lift—don’t Venmo them cash for a handyman. Don’t sigh and tell them to Google it.

Get in your car. Go there.

Put on your old clothes. Get under the sink with them. Let them hold the flashlight. Let them tell you how they used to do it in 1975.

Because one day, the garage will be clean. The tools will be sold. The phone will stop ringing. And you will give anything—absolutely anything—to be freezing cold, knuckles bleeding, listening to them tell you that you’re holding the wrench wrong.

The engine is still running. But the tank is getting low. Don’t wait until it stalls.

—

PART 2 — The Bolt Wasn’t the Hard Part

I thought the roar of that old engine was our ending.

I thought the crack of rust surrendering under our hands was the climax—the moment my father and I finally found the same language.

But two days later, in my glass tower of meetings and muted microphones, I learned the truth:

Sometimes the bolt is just the excuse people use… when what they really need is proof they still matter.

The first thing I noticed back in the city was the silence.

Not the quiet of peace—more like the quiet of a museum. The lobby was all polished stone and filtered air. The kind of place where nothing leaks, nothing squeaks, nothing smells like real life.

I stepped out of the elevator and caught my reflection in the mirrored wall.

Click the button below to read the next part of the story.⏬⏬