“There’s a new neighbor,” he said. “Bought the place two doors down. Young couple. Nice enough. They work from home. Sleep during the day. And the first time I fired up the truck after we fixed it—just to hear it breathe—they came over polite as church and asked if I could ‘keep it down.’”

He mimicked their gentle tone like it still stung.

“Keep it down,” he repeated, jaw tightening. “Like the sound of my life is a nuisance.”

I swallowed.

“That’s not what they meant,” I said, automatically.

Then I stopped myself.

Because maybe it was.

Maybe they didn’t mean harm. Maybe they were exhausted. Maybe they had a baby. Maybe they were just trying to live.

But intent doesn’t change impact.

And my father wasn’t reacting to one complaint.

He was reacting to a thousand tiny messages he’d been receiving for years:

You’re loud. You’re old. You’re inconvenient. You take up space.

He stared at his hands.

“Everywhere I turn,” he said softly, “I’m in the way.”

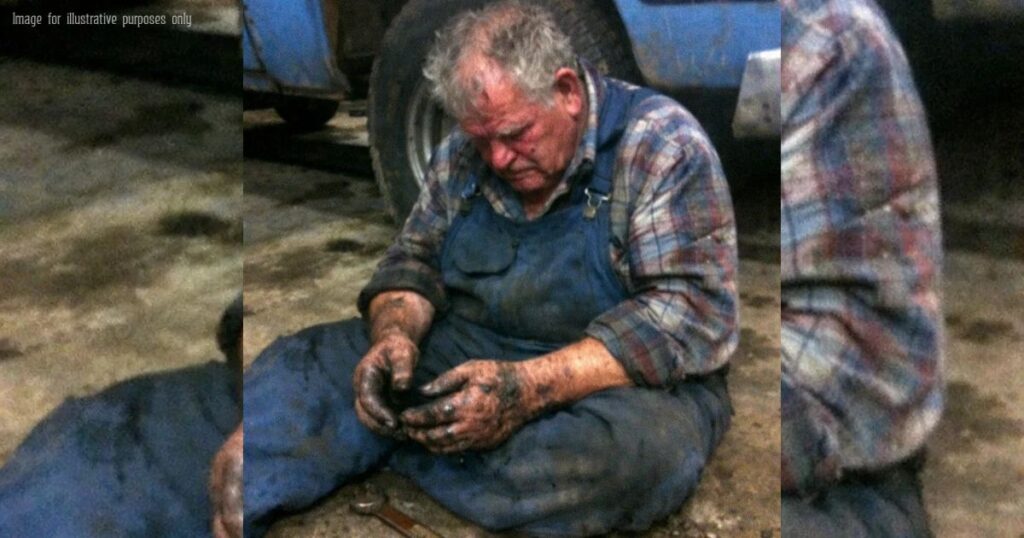

That night, I found him in the garage again.

Not under the truck—just sitting on that overturned bucket, looking at the tool chest like it was a photograph of someone he used to be.

I walked up quietly and sat on the cold concrete beside him.

For a long time, neither of us spoke.

Then he said, almost like a confession, “That call I made… it wasn’t really about the starter bolt.”

I didn’t move.

I didn’t interrupt.

He took a breath that sounded like rust breaking loose.

“I wanted to know,” he said, voice thin, “if you’d come. If I still had enough pull in this world to make my own son get in a car.”

My throat burned.

“Dad,” I whispered.

He shook his head fast, ashamed of the words now that they were out.

“I know,” he said. “It’s pathetic.”

“It’s not,” I said, and my voice surprised me with how hard it landed. “It’s the most honest thing you’ve ever said.”

He looked at me like I’d spoken another language.

And in a way, I had.

Because men like my father were taught that needing someone was weakness.

And people like me were taught that being needed was a burden.

We’d both been lied to—just in different dialects.

The next morning, we made a deal.

Not a sentimental, movie kind of deal.

A practical deal. The kind my father respected.

“Two hours,” I said. “That’s all I’m asking.”

He frowned. “For what?”

“For you to teach me something real,” I said. “And for me to teach you something you hate.”

He squinted. “I don’t hate anything.”

I raised my eyebrows.

He grunted. “Fine. What do you want to teach me?”

I pulled out my laptop and my phone.

“The world you keep calling stupid,” I said. “Because whether you like it or not, it’s the world that’s coming to your door with letters.”

He stared at the devices like they were snakes.

“You trying to turn me into one of those people who argue all day online?” he muttered.

“No,” I said. “I’m trying to make sure you don’t get run over by a system designed for people who don’t know your name.”

That got his attention.

So we did it.

I set him up with the basics—how to read notices, how to save documents, how to send an email that didn’t make him feel like he was begging.

He swore at the screen. He stabbed the wrong buttons. He called the cursor “that little idiot arrow.”

And then—slowly—he started to get it.

Not because he loved it.

Because he understood the point.

It wasn’t about becoming modern.

It was about staying sovereign.

Then his turn.

He handed me a wrench and pointed to a rusty old bicycle frame leaning against the wall.

“Your mother used to ride this,” he said. “We’re fixing it.”

I stared at the frame. The chain was stiff, the tires dead, the metal pitted with age.

“It’s not worth it,” I said without thinking.

My father turned his head slowly, like I’d just insulted a family member.

He didn’t yell.

He just said, “That’s what they want you to believe.”

And there it was.

The controversial thing nobody wants to admit out loud in a world built on upgrades and subscriptions and constant replacement:

We’re being trained to throw things away.

Things. People. Towns. Skills. History.

Anything that doesn’t fit cleanly into a shiny new interface.

We spent the afternoon bringing that bicycle back like it mattered—because it did.

When the wheels finally spun again, my father didn’t smile big.

He just nodded once, satisfied.

Then he said, “See? Still works. Just needed the right pressure in the right place.”

That evening, we sat at the kitchen table again. Cheap beer. Same creaking chairs.

My father looked at me and said, “You know what’s funny?”

“What?”

“All those years I acted like your job wasn’t real,” he said. “Like typing couldn’t build anything.”

He tapped the table with a knuckle.

“Today you showed me how to fight back with words and forms and buttons I hate. That’s a kind of wrench too.”

I didn’t answer right away because something in my chest was shifting.

He wasn’t just complimenting me.

He was making room for me in his world.

Then he said the line that I knew—deep down—would split people right down the middle if they ever heard it:

“Maybe we don’t have a generation problem,” he said. “Maybe we have a respect problem.”

Here’s the part that might make people argue in the comments, because it hits a nerve:

A lot of us say we’re “too busy” for our parents.

But we’re not too busy.

We’re just busy proving something.

Proving we made it. Proving we’re independent. Proving we’re not like them. Proving our lives are important enough to be full.

And meanwhile, our parents—especially the ones who were taught to be unbreakable—are sitting in quiet houses, shrinking themselves so they don’t inconvenience anyone.

Not because they don’t love us.

Because they don’t know how to ask without feeling ashamed.

My father didn’t call me because of a bolt.

He called me because he needed a witness to his life.

He needed someone to show up and say, You’re still the foreman.

And here’s the truth that some people will hate, because it demands something from all of us:

You can love your parents and still disagree with them.

You can hold boundaries and still show up.

You can be modern and still honor old hands.

But if your relationship with them is reduced to sending money, quick texts, and occasional holiday photos… don’t be surprised when they start believing they’re just another thing you replaced.

Before I left on Sunday, my father walked me out to the driveway.

The truck sat there, midnight blue under the gray sky, looking stubborn and alive.

He held out that bone-handled pocket knife again.

“You sure you don’t want it back?” I asked.

He shook his head.

“No,” he said. “It belongs where you are. Because you’re going to need it.”

“For what?”

He nodded toward my car, toward the road leading back to my clean life.

“To cut through the nonsense,” he said. “The kind of nonsense that tells you what matters without ever asking you.”

Then he looked me in the eye—really looked, the way he did when I was a kid and I’d done something that would shape me.

“Don’t wait for the next stuck bolt,” he said.

I swallowed hard.

“I won’t,” I promised.

And as I drove away, I realized something that might sound dramatic, but it’s the most practical warning I can give anyone reading this:

The phone doesn’t stop ringing all at once.

It slows down.

Fewer calls. Shorter calls. Less need.

Until one day the garage is quiet—not because everything is fixed, but because there’s nobody left to ask.

So here’s the question that will start a fight at every dinner table in America, and maybe it should:

If your parent called you tomorrow with a “stupid” problem… would you show up?

Or would you send a quick solution and call it love?

And if you’re a parent reading this—be honest:

Have you ever used a small problem as an excuse to find out whether you still matter?

Because my father did.

And it changed both of us.

Thank you so much for reading this story!

I’d really love to hear your comments and thoughts about this story — your feedback is truly valuable and helps us a lot.

Please leave a comment and share this Facebook post to support the author. Every reaction and review makes a big difference!

This story is a work of fiction created for entertainment and inspirational purposes. While it may draw on real-world themes, all characters, names, and events are imagined. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidenta