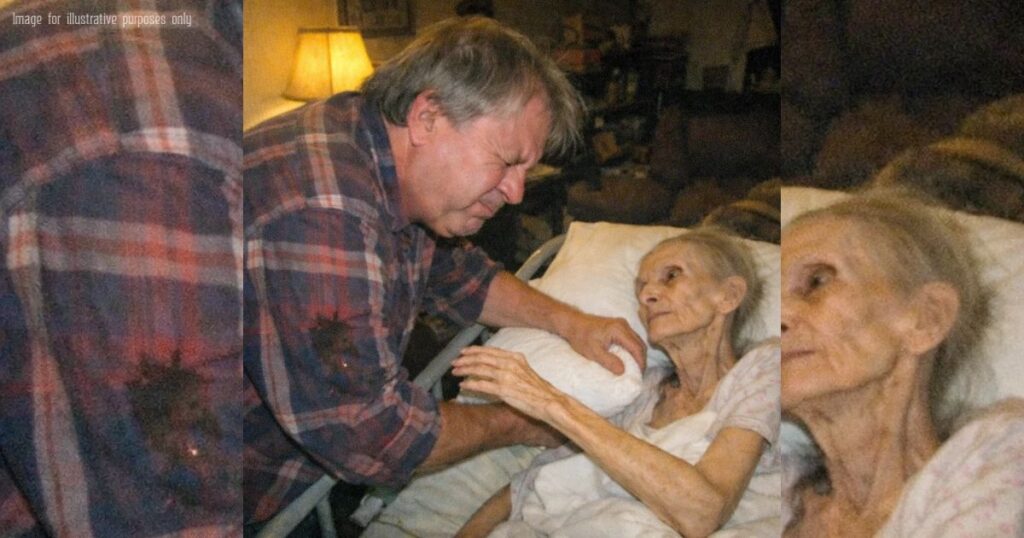

My wife begged me to hold her, to make her feel like a woman again, but I had to hold my breath because the smell of her slow death made my stomach turn, and when she leaned in for a kiss, I pretended to adjust her pillow just to turn my face away.

My name is Frank. I am sixty-eight years old, and I am a liar.

To the neighbors, I am the Saint of Maple Street. They see me sweeping the porch, hauling the oxygen tanks, and loading the wheelchair into the back of my rusted van. They stop by with casseroles and pity in their eyes, saying things like, “Eleanor is so lucky to have you,” or “They don’t make men like you anymore, Frank.”

I nod. I say thank you. I play the part of the stoic, iron-willed husband. But they don’t know what happens when the front door closes. They don’t know that I stand in the hallway for five minutes, hyperventilating, trying to summon the courage to walk into the living room where we put the hospital bed.

My secret, the one that eats me alive, is that my body rejects her.

It’s not just the smell of the disinfectant, or the metallic tang of the medicines, or the humid, sour odor of adult diapers that haven’t been changed fast enough. It is the smell of decay. It is the smell of a life that has gone stagnant. It has seeped into the drywall, into the carpet, into the very pores of my skin. No matter how much I scrub with industrial soap, I smell it on me.

Eleanor has late-stage dementia and complications from diabetes. She is the woman who once danced on tabletops at our wedding. She is the woman who could strip an engine block better than half the guys at the auto plant where I worked for forty years. Now, she is a skeleton wrapped in translucent, papery skin.

Last night was the worst.

It was 2:00 AM. The house was freezing because I keep the thermostat low to save on the heating bill. The “System”—that great, faceless bureaucracy we paid taxes into our whole lives—sent another letter yesterday. We are in the “coverage gap.” We aren’t destitute enough for full state aid, but we aren’t rich enough for private care. They told me that if I want full coverage for her nursing, I need to “spend down” our assets.

In other words: Sell the house. Sell the tools. Be homeless, and then we will help you.

I was sitting in the armchair, staring at that letter, when Eleanor woke up. For a rare, fleeting moment, the fog in her brain lifted. It happens sometimes—a cruel trick of the mind.

“Frankie?” she whispered.

I walked over. “I’m here, El.”

She looked at me, really looked at me, with a clarity I hadn’t seen in months. Her eyes were wet. “I’m scared, Frankie. I feel… I feel like I’m disappearing.”

“You’re not going anywhere,” I lied.

She reached out a trembling hand and placed it on my chest. Her fingers were cold, the nails brittle. “Come here,” she said. “Lie down with me. Just for a minute. Hold me like we used to. I want to feel safe.”

My brain screamed: Do it. She is your wife. She is the mother of your children. Comfort her.

But my stomach revolted.

As I leaned down, the smell hit me. It was a thick, sweet-rot scent rising from the sheets. I looked at the sores on her arms, the tubes snake-lined across the mattress, the yellowing of her eyes. My survival instinct kicked in. I didn’t see my beautiful Eleanor. I saw a biological hazard. I saw the thing that had stolen my retirement, my dignity, and my peace.

I froze.

I tried to force my body to lower itself onto the narrow mattress, but my muscles locked up. I held my breath until my lungs burned.

Eleanor saw it.

She saw the hesitation. She saw the micro-expression of disgust that I couldn’t hide fast enough. The light in her eyes—that rare, beautiful clarity—flickered and died. It wasn’t the dementia taking it away this time. It was me. I extinguished it.

“Oh,” she whispered. The word was so small, so filled with shame. She pulled her hand back as if she had burned it. “I’m sorry. I’m disgusting.”

“No, El, no,” I stammered, panic rising. “It’s just… my back. You know my back.”

“I know,” she said, turning her head to the wall. “Turn off the light, Frank.”

I stood there in the dark, listening to her weep softly into the pillow. I didn’t comfort her. I walked out of the room, went into the garage, sat inside my 1978 sedan—the project car I haven’t touched in three years—and I screamed until my throat bled.

I looked at my hands. Grease-stained, calloused hands. Hands that built things. Hands that worked sixty-hour weeks at the assembly line because we were promised that if we played by the rules, we’d have a “Golden Age.”

We bought the lie. We thought the hard part was the work. We didn’t know the hard part was the end.

I looked around the garage. This was supposed to be my time. We were supposed to be taking this car down Route 66. We were supposed to be drinking coffee on a porch, complaining about the weather, not counting pennies to decide between buying insulin or heating oil.

I realized then that I wasn’t just grieving for her. I was grieving for us. I was grieving for the illusion of control.

There is a unspoken brutality to long-term caregiving in this country. It strips you of your roles. I am no longer a husband; I am a nurse, a janitor, an accountant of misery. And she is no longer a wife; she is a patient, a burden, a case number on a rejected insurance claim.

I sat in that cold car and admitted the darkest truth of all: Part of me is waiting for her to die.

Not because I hate her. God, I love her more than my own life. But I want her to die so I can love her again.

I want this version of her—the one that smells of sickness, the one that cries in shame, the one that is slowly bankrupting our legacy—to be gone. I want to be able to close my eyes and remember the woman with the oil smudge on her cheek who laughed when I dropped a wrench. I want to love her memory, pure and clean, without the need to hold my breath.

I fell asleep in the front seat of the car.

When I woke up, the sun was cutting through the dusty garage windows. I felt the stiffness in my joints. I walked back into the house.

The smell was still there. The pile of medical bills was still on the table. The letter from the insurance agency was still mocking me.

I walked into the living room. Eleanor was awake, staring at the ceiling. She looked small.

I went to the sink and filled a basin with warm water and rose-scented soap—the expensive kind I bought for her birthday, the one we usually save for special occasions. I soaked a washcloth.

I went to the bed. “Good morning, El.”

She didn’t look at me. “I smell,” she mumbled.

“We can fix that,” I said.

I pulled up a chair. I didn’t hold my breath this time. I breathed it in—the sickness, the rot, the reality of our life. I forced myself to inhale it deep into my lungs until it stopped smelling like horror and just smelled like truth.

I started washing her face. Gently. Then her hands.

“I’m sorry about last night,” I said, my voice cracking. “I’m an old fool with a bad back and a weak heart. But I’m here.”

She looked at me, her eyes cloudy again, the clarity gone. “Who are you?” she asked.

The question hit me like a physical blow. But then, I looked at her hands—the same hands that held mine when we buried my mother, the same hands that signed the mortgage papers on this house thirty years ago.

“I’m the guy who cleans the car,” I said softly. “And I’m not going anywhere.”

She smiled, a faint, vacant smile. “Okay.”

I am Frank. I am sixty-eight years old. I am tired, I am broke, and I am scared. But I realized something this morning.

True love isn’t the romance of the past. It isn’t the ‘Good Old Days’ when the factories were open and the cars were made of steel. True love is what happens when the dream rots. True love is doing the ugliest work in the world with gentle hands, even when no one is watching, even when the person you are doing it for doesn’t know who you are.

I finished washing her, combed her thin grey hair, and sat there holding her hand as the morning news played softly in the background, talking about the economy, the stock market, the things that don’t matter in this room.

I didn’t hold my breath. I just held her hand.

—

PART 2

The morning news kept talking, like it could fill the room with numbers and make the smell disappear.

I sat in the folding chair beside Eleanor’s bed with her hand in mine, listening to a cheerful voice explain how “consumer confidence” was trending up, how “markets” were “optimistic,” how the world was “moving forward.”

In our living room, nothing moved forward.

Eleanor’s fingers were light as bird bones. Her skin felt like warm paper. Every so often her thumb twitched, like her body was trying to remember an old habit—how she used to tap my hand twice when she wanted me to stop talking and just be with her.

I leaned in closer, because I was trying. Because I meant it.

And because—if I’m telling the truth—I was afraid that if I let go, she would evaporate.

The phone rang at 9:07.

I stared at it for a full three rings before I answered, like it might be a debt collector or another letter with a human voice.

“Dad?” My daughter’s voice. Claire. Fifty-two years old and still able to turn me into a teenager with one syllable.

“Yeah,” I said.

Click the button below to read the next part of the story.⏬⏬