Three weeks after Jackson told his mother about the magic drawer, my secret stopped belonging just to Room 204.

It belonged to the internet.

It started with a video.

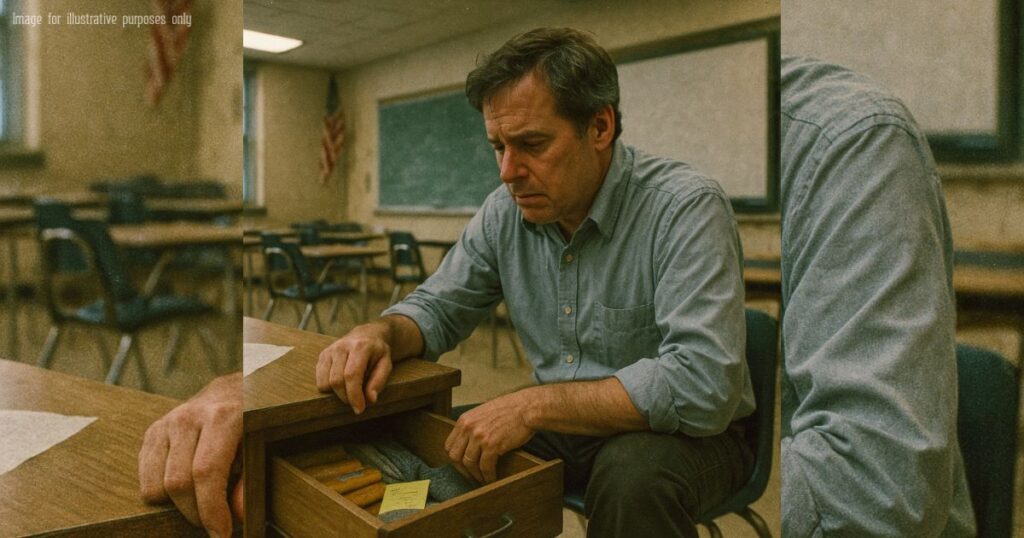

I didn’t know about it at first. It was a thirty-second clip, filmed sideways on a cracked phone screen, shaky and badly lit. You never even saw my face. Just my hands opening the bottom drawer, the one with the red “ADMINISTRATION ONLY” sticker, and a quick glimpse of granola bars, socks, and sticky notes.

The caption said:

“My teacher has a SECRET drawer so kids don’t go hungry. He could get fired for this.”

Someone set the clip to emotional music. A few students shared it that night. Then their cousins shared it. Then someone stitched it with a rant about “how teachers are doing more than politicians.”

By the time I woke up in the morning, it had half a million views.

By lunchtime, it had 2.3 million.

I learned all of this because a sophomore burst into my classroom before first period, panting.

“Mr. Vance, you’re FAMOUS,” she said, waving her phone. “You’re all over my feed.”

I took the phone and watched the video in stunned silence. The comments were a hurricane.

“He’s a hero.”

“This broke my heart. We need more teachers like him.”

“Why is a teacher doing this? Where are the parents??”

“This is literally against district policy.”

“Imagine being the parent whose kid is sneaking food like a charity case.”

“THIS is why our taxes are so high and still kids are hungry.”

I handed the phone back, my stomach twisting.

Because here’s the thing: I never wanted to be content.

I never wanted to be a symbol or a battleground for strangers with usernames like “PatriotDad84” and “NoKidsJustVibes.”

I just didn’t want Mia to faint in my classroom.

By third period, half the staff knew. By fifth period, our Principal knew. By sixth period, the District Office knew.

By seventh period, the intercom buzzed.

“Mr. Vance, please see me in my office after the last bell,” the Principal’s voice said. Calm. Too calm.

The kids all went “ooooh,” like they do in every American school since the dawn of time. I smiled it off, but my hands were shaking as I picked up the dry-erase marker.

I spent the last ten minutes of class pretending to care about the causes of the Great Depression while my brain replayed every policy I’d ever signed.

Unapproved food. Liability. Allergies. Equal access. Appropriateness.

The final bell rang. The room emptied in a whirl of backpacks and gossip about my alleged “fame.”

I walked to the office feeling like I was on my way to a sentencing hearing.

The Principal—Ms. Turner—wasn’t alone. Sitting next to her was a man in a neat shirt and tie I’d never seen before.

“Tom,” she said gently, “this is Mr. Alvarez. From the District.”

Of course he was.

He smiled the way people smile before they tell you they’re about to take something from you.

“We want to talk about… the drawer,” he said.

I sat down. “The drawer,” I repeated, like we were discussing a character from a book and not the thing keeping my students from going to bed hungry.

Mr. Alvarez folded his hands. “Let me start by saying: nobody here thinks you had bad intentions.”

That’s how you know you’re in trouble in modern America. When the sentence starts with “nobody thinks you had bad intentions.”

“But you understand,” he continued, “that the video shows potential violations of policy. Food distribution, medical risk, privacy concerns, the optics of students needing… charity… from a teacher.”

Optics.

I thought of Mia’s duct-taped shoes. Jackson’s damp hoodie. The crumpled dollar bill in the drawer.

“Optics are not my first concern when a child tells me it isn’t their turn to eat,” I said quietly.

There was a long silence.

Ms. Turner looked between us like a referee at a boxing match she didn’t want to officiate.

Mr. Alvarez sighed. “This has gone viral,” he said. “We’ve had emails all morning. Some are incredibly supportive. Some are… not.”

“Not,” in this case, meant:

Why is this man feeding other people’s kids?

Is he shaming families?

Is this indoctrination?

Is this favoritism?

Is he collecting data on them?

People who had never set foot in our cracked-tile hallways suddenly had opinions about my bottom drawer.

“We’re going to have a School Board meeting about it,” Mr. Alvarez said. “Tonight.”

“Tonight?” I repeated.

He nodded. “Parents are already organizing to speak. Some are calling you a hero.” He hesitated. “Others are demanding an investigation.”

I felt tired down to my bones.

“Do I… need a lawyer?” I asked.

Ms. Turner shook her head quickly. “No one is accusing you of a crime, Tom.”

Not yet, I thought.

“For now,” Mr. Alvarez said, “we need you to stop using the drawer. Temporarily. Remove all food items. Lock it. We’ll work on a district-approved solution—maybe a formal ‘care closet’ with proper forms, permission slips, allergy lists. Something structured.”

Something slow, he meant.

Something that would take months of committees and safety audits while my kids still came to school with empty stomachs and wet socks.

That afternoon, I went back to Room 204 and opened the drawer.

The granola bar, the hat, the tissues, the dollar, the notes—they all stared up at me like evidence.

I took a deep breath and reached for the snacks, feeling like I was betraying them.

“Mr. V?”

I looked up. Jackson stood in the doorway, backpack slung over one shoulder.

“Hey, J,” I said, trying to sound normal. “What’s up?”

He looked from my face to the drawer. His eyes narrowed.

“They’re making you shut it down, aren’t they?” he said.

It wasn’t really a question.

“Just for a bit,” I said. “Adults are talking. Policies. Meetings.”

Jackson stepped inside, jaw clenched.

“They’re mad you’re feeding us?” he asked. “That you let us feel… not poor for five minutes?”

“Some people are worried about safety,” I said carefully. “About doing it the ‘right’ way.”

He laughed, but it had no humor in it.

“The right way,” he said. “Right. Because the ‘right way’ has been working so great.”

He pointed toward the hallway.

“You know what I hear every morning when I walk in? Teachers arguing about test scores. Guests talking about ‘future readiness.’ They write big words on the banners in the gym. ‘Resilience.’ ‘Perseverance.’ But when you actually help us survive the week, they freak out.”

“Not all of them,” I said.

He nodded slowly. “Not all of them,” he conceded. “Just the ones who don’t know what it’s like to count slices of bread.”

He stepped closer to the desk.

“Are you going to the meeting?” he asked.

“I don’t have a choice,” I said.

“We’re coming,” he replied.

Later that evening, I sat in a hard plastic chair in the crowded auditorium, feeling like a defendant on a reality show.

The School Board sat in a row up front. Cameras and phones were everywhere. Someone was live-streaming.

A giant printed screenshot of the video thumbnail—my drawer, mid-open—was taped to a poster board near the front.

Handwritten above it: “IS THIS A HERO OR A LIABILITY?”

If you want to know what America is like right now: we will put that question on a sign before we ask why a drawer like that is needed in the first place.

Parents took turns speaking.

A woman in a neat blazer went first.

“I appreciate that this teacher cares,” she said. “But this is not his job. It sends the message that parents are failing, that the school is responsible for everything. Where does it stop? Today it’s snacks. Tomorrow it’s rent money.”

A man in work boots spoke next.

“My kids go to this school,” he said. “We struggle, but we make it work. I don’t want my children getting ‘charity’ behind my back. If they’re hungry, they can come to me. This makes us look like we aren’t trying.”

Then Jackson’s mother stepped up to the microphone.

Her hands shook as she unfolded a piece of paper.

“I work two jobs,” she began. “I clean offices until midnight, then get up at five to work at a warehouse. I am trying.”

Her voice cracked on the last word.

“My son didn’t tell me he was hungry because he didn’t want to make me feel worse. He was taking care of me by staying quiet. That drawer…” She paused to compose herself. “That drawer gave him food and dignity. If you think that makes you look bad as parents, I don’t know what to tell you. Because I felt something different. I felt seen.”

The room was very quiet.

A Board member cleared her throat. “We understand the emotion here. But we also have to think of fairness. Liability. Are all students benefiting equally? Is this sustainable? Is it appropriate for one teacher to make these decisions alone?”

Click the button below to read the next part of the story.⏬⏬