“But,” I continued, “if you are ever standing in front of a shelf and the world feels too loud, and you don’t know which ‘sauce’ to pick, you can call me. Or if you just want to tell someone that your garlic didn’t burn this time.”

He held the paper carefully, like it might crumble. “I… I haven’t called anyone in a long time,” he admitted. “People stopped checking in after the funeral. I didn’t blame them. Life goes on.”

“Life goes on,” I agreed. “It just goes on better when we check on each other.”

For three weeks, nothing happened.

I went to my appointments. I watered the plant in the kitchen window. I played the same radio station Henry used to fall asleep to in his recliner. Sometimes I wondered if I’d imagined the whole encounter, if Robert was just a character my lonely mind had invented to feel needed again.

Then, one Tuesday afternoon, my phone rang.

The number was unfamiliar. I almost let it go to voicemail. Old habits—avoid telemarketers, avoid scams, avoid anything that smells like trouble. But something in my gut nudged me. I answered.

“Hello?”

There was a pause, then a fragile voice. “Is this… is this Margaret?”

“Yes,” I said, sitting down at the kitchen table. “Is this Robert?”

Another pause. I heard him exhale, shaky. “I didn’t burn the garlic,” he blurted out.

I smiled so hard my cheeks hurt. “Well, that’s excellent news.”

“And I wrote it down,” he said, words tumbling now. “Your idea. My own version. I wrote, ‘Heat the oil first. Don’t get distracted. Think about Ellen, but not too much or you’ll cry and forget the pan.’” He gave a tiny, embarrassed laugh. “Is that silly?”

“It’s perfect,” I said. “Grief-proof cooking instructions. Patent pending.”

“I, uh…” His voice softened. “I wondered… would you… would you maybe like to come over on Sunday? For sauce? It feels wrong to eat it alone now that I’ve talked about it so much. We could… I don’t know… compare notes on burnt pies and smacked garlic.”

The invitation hung in the air between us.

Henry’s empty chair seemed to lean closer. For a moment, fear jabbed me—fear of seeing another man’s grief up close, fear of being seen in mine. Of how quiet his house might be. Of how quiet mine had been for so long.

But underneath the fear, there was something else.

“You know what, Robert?” I said. “I would like that.”

Sunday came with a light dusting of snow on the lawns and a sky that couldn’t decide if it wanted to be gray or blue. I dressed in my good sweater and the scarf my granddaughter had knitted crooked last winter. I baked a loaf of simple bread—nothing fancy, just flour, water, and the hope that it wouldn’t embarrass me.

Robert’s house was a small brick bungalow with a neat yard and a wind chime tinkling softly by the front door. He opened it before I could knock twice.

“You found it,” he said, relief clear in his face.

“As you can see, I am a woman of many talents,” I replied. “I can read street signs.”

He stepped aside to let me in. The warmth hit me first, then the smell.

Tomatoes, garlic, onions, something sweet underneath. The kind of smell that seeps into curtains and memories.

Photographs lined the hallway. A young Ellen in a sundress, her hair piled on her head. Robert in a suit that didn’t quite fit, standing beside a car from another decade. Children at different ages, then grandchildren, then everyone a little grayer.

In the dining room, the table was set for three.

I hesitated at the doorway, my eyes catching on the third plate. The napkin folded just so. The spoon resting on the edge of the empty bowl.

Robert followed my gaze. “I know it’s silly,” he said quietly. “I just… I’m not ready to set the table for two yet. But I thought it would be ruder to set it for one when you were coming.”

My throat tightened. “Love isn’t silly,” I said. “We can leave her place just as it is.”

We sat down. The sauce was richer than I expected, with a hint of something I couldn’t quite place.

“Carrots,” he said proudly when I asked. “She used to sneak them in, said it made the sauce sweeter so she could use less sugar.”

We ate. We talked. About the early days of their marriage, when he burned everything he touched in the kitchen. About my first year without Henry, when I went three days once eating nothing but toast because I couldn’t stand to cook for one.

We laughed. We cried. At one point, we both reached for the bread at the same time and our hands bumped, and it felt less like an awkward moment and more like proof that we were both still here. Still reaching.

When I left, hours later, the air outside felt colder, but I felt less alone in it.

On my way home, I stopped at the store for milk. The aisles were just as noisy, the shelves just as crowded. But now, everywhere I looked, I saw possibilities.

A young man helping an older woman reach a box on a high shelf.

Lena at the register, leaning down to smile at a child clutching a pack of stickers.

An older couple arguing softy over which bread was “the good kind.”

The world was still rushing, impatient and distracted. But here and there, like small porch lights flickering on at dusk, were these tiny acts of gentleness.

Weeks later, I would sit at my own kitchen table, pen in hand, and start a list like Robert’s.

Things Henry Did.

Not because I was afraid of forgetting, but because remembering felt like another kind of sauce simmering on the stove—a way to keep his love in the air.

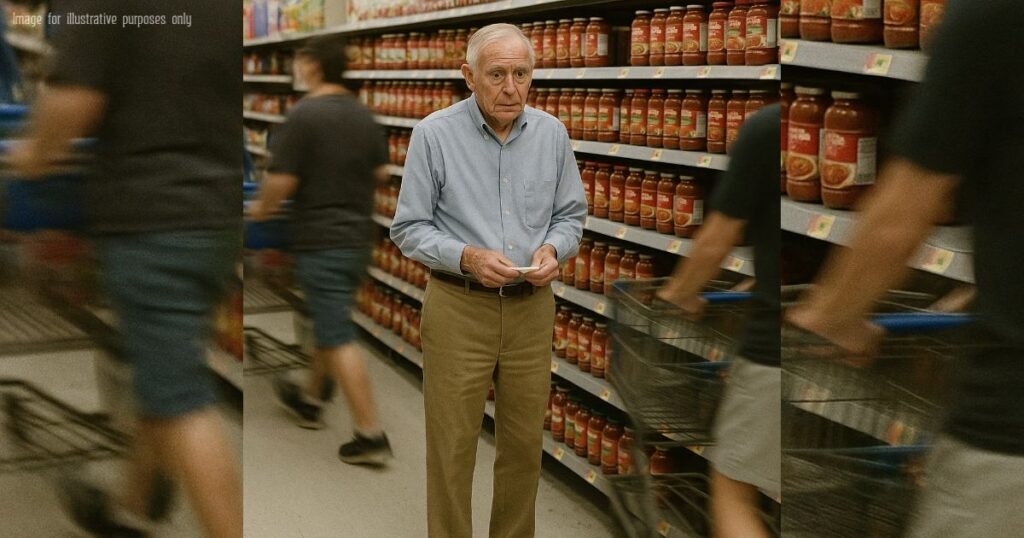

If you ever find yourself in a checkout line behind someone moving too slowly, or staring too long at a shelf, I hope you will remember Robert. Remember his trembling hands, his courage to try, his empty chair set carefully at the table.

You can’t fix their grief.

But you can stand beside it for a moment.

And sometimes, that’s all it takes to turn a fluorescent-lit warehouse into holy ground