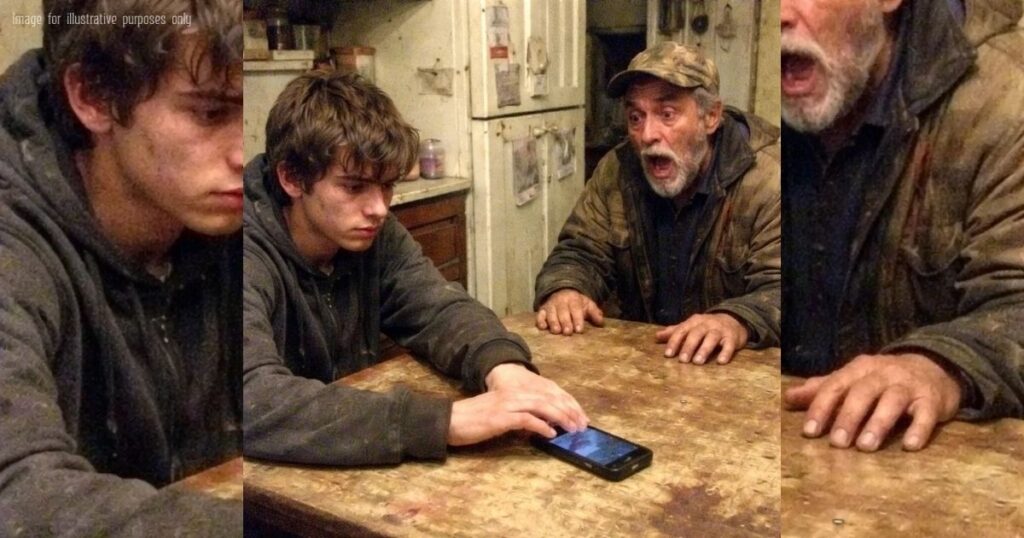

When my fourteen-year-old grandson placed his smartphone on the kitchen table and quietly asked me to sell it, I didn’t celebrate. I felt a cold knot of absolute terror tighten in my stomach.

For a kid in 2026, voluntarily giving up that device isn’t a lifestyle choice. It’s a surrender. It’s the white flag of a soldier who has nothing left to defend.

“Are you sure, Leo?” I asked, wiping my hands on a grease-stained rag. I was fresh in from the garage, smelling of oil and sawdust—the perfume of my generation.

“I don’t need it, Grandpa,” he said. He didn’t look at me. He looked at his sneakers. “It’s just… noise.”

He went to his room and closed the door. The silence that followed was heavier than the engine block sitting on my workbench.

I’m a simple man. I spent forty years fixing transmissions. If a gear grinds, you open the box, find the broken tooth, and replace it. You don’t ignore the noise until the whole thing explodes.

The next morning, I didn’t go to the garage. I drove my rusted pickup truck to the high school parking lot. I didn’t go inside. I just parked across the street, lowered the brim of my cap, and waited for the lunch break.

I needed to see the diagnostic before I could attempt a repair.

When the bell rang, a sea of teenagers flooded the courtyard. They didn’t look like the kids I grew up with. We used to run, shout, shove each other, and laugh. These kids walked in clusters, but their eyes were glued to the palms of their hands.

Then I saw Leo.

He was sitting on a concrete bench near the fence, eating a sandwich. He wasn’t alone, but he was the loneliest soul in that lot. Three boys stood near him. They weren’t hitting him. They weren’t stealing his lunch money. That would have been too simple. That would have been a problem I knew how to fix.

Instead, they were holding their phones up. Recording.

One boy pretended to trip near Leo, spilling a soda on the ground, just inches from Leo’s shoes. Leo flinched. The boys laughed—not a gut laugh, but a performative, cruel cackle meant for an audience. They zoomed in on his reaction. I could see the flash of the cameras.

Leo didn’t fight back. He didn’t yell. He just froze, staring at his sandwich, trying to make himself invisible. He was content. He was a meme waiting to be uploaded. He was being humiliated not just in front of three bullies, but potentially in front of the entire school, the entire town, forever.

My knuckles turned white on the steering wheel. In my day, if you had a problem, you met behind the gym. You fought, you got a bloody nose, you shook hands, and it was over. The pain was sharp, physical, and temporary.

This? This was psychological warfare. This was a slow poison that followed you home, into your bedroom, under your covers, buzzing in your pocket at 3:00 AM.

I marched into the administrative office ten minutes later.

The principal was a young woman with a polished smile and a desk free of any actual paper. She listened to me, nodding sympathetically, typing notes into her tablet.

“Mr. Frank,” she said, her voice smooth like synthetic oil. “We take student well-being very seriously. We have a Zero Tolerance policy on bullying.”

“Then do something,” I said, my voice rising. “I just watched three vultures circling him. They’re posting it online right now.”

She sighed, clasping her hands. “That’s the tricky part. Unless the recording happens inside a classroom or involves physical altercation, our jurisdiction is limited. We can’t police personal devices without violating privacy policies. We can’t control what happens on social media servers. We have to be very careful about liability.”

Liability. Jurisdiction. Privacy policies.

I looked at the framed certificates on her wall. “Ma’am, with all due respect, you’re so terrified of a lawsuit that you’re letting a boy’s spirit bleed out in your courtyard. You’re protecting the system, not the child.”

“We can offer Leo a session with the guidance counselor to discuss resilience strategies,” she offered.

I stood up. I adjusted my cap. “Resilience isn’t something you talk about in an air-conditioned office. It’s something you build.”

I walked out. I didn’t pull Leo out of school. That would be running away. But I realized that the school couldn’t save him. The modern world couldn’t save him because the modern world was the problem.

That evening, when Leo came home, I didn’t ask him about his day. I didn’t offer him a cookie or a platitude.

“Put your boots on,” I said. “Come to the garage.”

Leo looked confused but followed me. The garage was my sanctuary. It was cold, smelling of gasoline and old metal. In the center sat my project: a 1969 muscle car, a shell of rusted glory that I’d been restoring for years.

“Grandpa, I have homework…”

“It can wait. I need hands,” I said. I pointed to the transmission sitting on the bench. “Do you know what this is?”

“A motor part?”

“It’s a manual transmission. A stick shift,” I said. “It’s not like the cars today where you press a pedal and the computer does the thinking. With this, you have to feel the engine. You have to listen. If you’re not paying attention, you stall. If you’re too rough, you strip the gears. It demands your respect.”

I handed him a wrench. It was heavy, cold, and real.

“This bolt is stuck,” I lied. “My arthritis is acting up. I need you to break it loose.”

Leo took the wrench. He looked at his soft hands, then at the greasy bolt. He applied pressure. Nothing happened.

“Lean into it,” I commanded. “Don’t ask it to move. Make it move.”

He grunted, putting his slight weight behind the tool. The wrench slipped, and he banged his knuckle against the casing.

“Ow!” He dropped the wrench, clutching his hand. A small drop of blood welled up.

I didn’t coddle him. I tossed him a rag. “Wipe it off. Try again.”

He looked at me with shock, perhaps waiting for an apology. When he saw none, a flash of anger crossed his eyes. Good. Anger is better than despair. Anger is fuel.

He picked up the wrench. He gritted his teeth. He pulled with everything he had, his face turning red.

Creak. The bolt turned.

“I got it,” he breathed, looking at the loosened metal. He looked at his hands. They were dirty. His knuckle was throbbing. But he was smiling.

For the next three hours, we didn’t speak about school. We didn’t speak about feelings. We spoke about torque, about leverage, about how rust is just nature trying to take back what we built, and how it’s our job to fight it.

We spent the next month in that garage. Every evening.

I watched my grandson change. It wasn’t overnight. But there is something profound about physical labor that heals the soul. When you are under a car, wrestling with a suspension strut, you can’t check your notifications. You can’t worry about what someone said about you on an app. You have to be present. You have to be strong.

One Friday night, we finally got the engine running. The roar of that V8 was deafening, a symphony of raw power that shook the tools on the walls.

Leo sat in the driver’s seat, revving the engine, feeling the vibration rattle through his bones. He looked alive. He looked dangerous, in the best possible way.

“Grandpa,” he shouted over the noise. “Can I drive it to school on Monday?”

I leaned through the window. “It’s a stick shift, Leo. It’s hard to drive. You’ll stall it in the parking lot. People might laugh.”

Leo looked at me. His hands were stained with grease that wouldn’t wash off for days. He looked at the shifter, then he looked me in the eye.

“Let them laugh,” he said. “They don’t know how to drive this. I do.”

That was the moment. The “click” of the gear falling into place.

He drove it to school. It was loud. It smelled like gasoline. It was a dinosaur in a parking lot full of silent, plastic electric pods. When he stalled it at the entrance, a few kids laughed.

But Leo didn’t shrink. He restarted the engine, revved it loud enough to drown out their giggles, and parked it perfectly.

When he got out, he didn’t look down. He didn’t check for an invisible audience. He walked toward the building with his head up, his knuckles still carrying the faint scars of the work he’d done. The bullies were still there, phones in hand, ready to feed on weakness.

But they didn’t film him.

Predators know when the prey has changed. They know when the gazelle has become a lion. There was a weight to Leo now, a gravity that hadn’t been there before. He had built something with his own hands. He knew the difference between the artificial reality on a screen and the undeniable reality of steel and fire.

We can’t stop the world from moving forward. We can’t ban the phones or sue the internet. But we can give our children something real to hold onto.

We can teach them that their value isn’t determined by a ‘like’ button or a comment section. Their value is in what they can build, what they can fix, and how much they can endure.

Sometimes, to move forward, you have to shift into a lower gear. You have to get your hands dirty. You have to shut out the noise and listen to the engine.

Don’t just buy your kids devices. Buy them tools. Teach them that in a world of fragile glass screens, it’s okay to be made of steel.

—

Part 2

The Monday Leo drove that old stick shift to school, I thought the story would end the way stories used to end—simple. Problem identified. Problem fixed. Boy walks taller. Bullies slink away.

I was wrong.

Because in 2026, nothing ends when the bell rings. It just changes screens.

That afternoon I found a sheet of paper shoved under my windshield wiper in the grocery store parking lot. Not a ticket. Not an ad.

A screenshot.

It was a still image of my grandson’s face the moment the engine stalled at the school entrance—eyes wide, jaw clenched, that half-second between embarrassment and grit. Someone had frozen him in time like a bug pinned to cardboard.

Across the top, in thick black letters, it read:

“GRANDPA MADE HIM DO THIS IN PUBLIC.”

Underneath, a caption someone had typed:

Click the button below to read the next part of the story.⏬⏬